Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

THE FLIGHT OF THE GOEBEN AND THE BRESLAU

by Admiral Sir Berkeley Milne

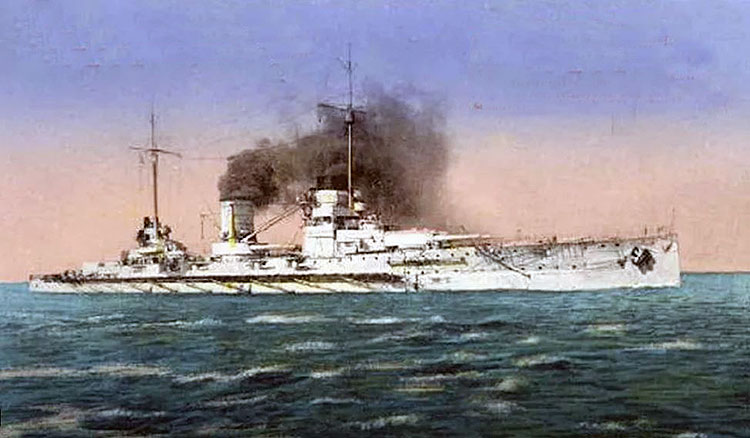

SMS Goeben.

Preface

AFTER the publication in March 1920, of the “Official History of the War: Naval Operations, Vol. I.,” by Sir Julian S. Corbett, I represented to the First Lord of the Admiralty that the book contained serious inaccuracies, and made a formal request that the Admiralty should take action in the matter. As the Admiralty did not think proper to accede to my request, I have thought it right to publish the following narrative.

A. BERKELEY MILNE,

Admiral

January 1921.

I. OFFICIAL RESPONSIBILITY

In justice to the public, to the officers and men who served under my command, and to my own reputation, I have thought it right to publish the following narrative of the events in the Mediterranean immediately preceding and following upon the outbreak of war, concerning which there has been, and is, some unfortunate misapprehension.

During the war, when secrecy with regard to naval operations was necessary, it was natural that the public anxiety should find expression in conjectures, and that false impressions should prevail. I select the following passages from Hansard as examples : " Hansard (House of Commons), 31st July, 1916. Escape of the Goeben and Breslau (Dispatches).

"Commander Bellairs asked the First Lord of the Admiralty, in view of the fact that the disasters of the Dardanelles and the Baghdad advance are about to be inquired into by Commissions, whether he is aware that the entry of Turkey into the war originated in the escape of the Goeben and Breslau from Messina to the Dardanelles in August 1914; and whether he can now publish the dispatches dealing with the matter, together with the dispositions of ships of which the Board of Admiralty have expressed their approval?

“Dr. Macnamara : The Admiralty have hitherto only published dispatches which deal with actual engagements, and not reports on the disposal of His Majesty’s ships, whether or not those dispositions succeeded in bringing about an engagement. My right hon. friend (the First Lord, Mr. Balfour), does not propose to depart from this well-established practice. He must not be assumed as giving unqualified concurrence to the view of my hon. and gallant friend that the entry of Turkey into the war originated with the arrival of these two ships at Constantinople.

"12th March, 1919.

“Mr. H. Smith asked the First Lord of the Admiralty whether he will lay upon the Table of the House the Report of the proceedings of the Court of Inquiry which inquired into the circumstances attending the escape of the Goeben and Breslau, and which acquitted Admiral Sir Berkeley Milne of all responsibility therefor?

“Dr. Macnamara : As stated in reply to a question by my hon. friend the Member for Portsmouth North, on the 26th February, no Court of Inquiry was held in the case of Admiral Sir Berkeley Milne. The Admiralty issued a statement on the 30th August, 1914, to the effect that :—

“The conduct and dispositions of Admiral Sir Berkeley Milne in regard to the German vessels Goeben and Breslau have been the subject of the careful examination of the Board of Admiralty, with the result that their Lordships have approved the measures taken by him in all respects.’ "

These, and other perfectly correct statements of the Government on the subject, did not, however, serve to dispel the misapprehensions to which I refer.

The Government have consistently refused to publish the documents concerning the opening of the war in the Mediterranean, the reason for their refusal being that the history of the affair would be related in the “Official History” of the war, in preparation by Sir Julian Corbett. On the 15th November, 1920, for instance, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Admiralty stated in the House of Commons that, “so far as the near future is concerned, it is not proposed to publish the documents in regard to the escape of the Goeben . . . the matter had already been . . . dealt with in the ' Naval History of the War.’"

It was, therefore, to be expected that the facts of the episode in question would be impartially set forth in the “Official History of the War: Naval Operations,” by Sir Julian S. Corbett, Vol. I., published in March 1920.

That expectation has not been fulfilled. Nor has the Admiralty thought proper to take any action to correct the erroneous impression which, in my own view, is disengaged by the official historian’s presentation of the case. Indeed, a reference to the statement of Sir James Craig, quoted above, shows that the Admiralty profess to regard the account of the matter written by Sir Julian Corbett as an exact version of the documents upon which the historian’s version of them was founded. It is not a conclusion I find myself able to accept.

If, writing as an independent historian, Sir Julian Corbett was impelled to criticize the conduct of the naval operations by the officers in command of them, I should hold that the Admirals at sea, being professional seamen, were probably better able to judge of the requirements of the situation than an amateur on shore, and the matter would resolve itself into a simple difference of opinion. But the case is not so simple as that. Neither the Committee of Imperial Defence nor the Admiralty can be absolved from a definite share in the responsibility for the “Official History.”

The First Lord of the Admiralty stated on 18th February, 1920, that the “Official History” is being compiled under the direction of the Committee of Imperial Defence (Hansard, 18th February, 1920). The same statement was made by the Parliamentary Secretary to the Admiralty on 27th October, 1920 (Hansard).

The Prime Minister informed the House of Commons on 1st November 1920, that “Sir Julian Corbett, I understand, is writing the official account of the war from the Admiralty point of view” (Hansard, 1st November, 1920).

On the cover of the “Official History" appear the words “Official History of the War.” Inside, facing the title-page, appears a note, as follows: “The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty have given the Author access to official documents in the preparation of the work, but they are in no way responsible for his reading or presentation of the facts as stated.” The contradiction is obvious.

Sir Julian Corbett’s own account of his position is explained by him in the following letter, published in “The Nineteenth Century and After,” November 1920, referring to an article by Admiral Eardley Wilmot appearing in the previous issue :—

“WHO LET THE GOEBEN ESCAPE?

“ To the Editor of * The Nineteenth Century.’

" Sir,

" In an able and dispassionate appreciation of the escape of the Goeben appearing in your issue of this month, your contributor gives the weight of his name to a widely prevailing impression which I would beg leave to correct.

"Referring to the ‘Official Naval History of the War,’ as the main source for the facts of the case, he says, *As regards this incident, it has evidently been heavily censored.’ That such an impression is natural, I do not deny, but it is entirely untrue. I was given the freest possible access to the secret files which contain the telegrams that passed between the Admiralty and the Admiral, as well as to the instructions, logs and the rest, and from these sources a narrative was constructed to the best of my ability. After being tested for accuracy of detail by senior officers who were engaged in the operations, it was submitted to the Admiralty, and, after careful examination, returned to me, with a few suggestions as to the wording of certain passages. Beyond this, no ‘censoring’ took place, and the tenour of the comments remained unchanged.[1]

"The narrative was not censored at all, nor was any telegram relating to operations ignored or misrepresented in the text.

“In regard to this episode—and indeed to the whole volume—I can only look upon the Admiralty ‘censoring,’ such as it was, as frank assistance in securing an accurate, full and impartial record of what occurred.

“Yours obediently,

"(Sgd.) JULIAN S. CORBETT.”

[1] My italics.—А. В. M.

It will be observed that Sir Julian Corbett, while denying that the Admiralty “censored" his account of the matter, definitely states that it was submitted to the Admiralty, and that their Lordships made “a few suggestions as to the wording of certain passages.” He adds that “the tenour of the comments remained unchanged.”

It is, therefore, clear, first, that the Admiralty reserve to themselves the right to suggest alterations in the text; second, that, in the case under consideration, their Lordships made no such alterations in "the tenour of the comments.” It is the tenour of the comments ” to which I take grave exception. " I can only look upon the Admiralty ‘censoring,’ such as it was,” writes Sir Julian, " as frank assistance in securing an accurate, full and impartial record of what occurred.” It is a view with which I regret I cannot agree. Sir Julian Corbett further states that his narrative was “tested for accuracy of detail by senior officers who were engaged in the operations.” That is a statement I am quite unable to understand. I was Commander-in-Chief in the Mediterranean at the period in question; I came home in August 1914; and neither then nor subsequently did Sir Julian Corbett communicate with me. I did not see his account of the episode until the “Official History" was published in March 1920. I regard it as extremely unfortunate (at least) that Sir Julian Corbett should permit himself to assert, or to imply, that his narrative was submitted to me before publication. After the publication of the book, I called upon Sir Julian, and, expressing my regret that he had not consulted me, when I should have had great pleasure in giving him all the assistance in my power to obtain accurate information, I asked him why he had not availed himself of my services. Sir Julian was, however, unable to afford me any explanation of his failure to do so.

According to the statements of Ministers, Sir Julian Corbett is compiling his history “under the directions of the Committee of Imperial Defence,” and “from the Admiralty point of view.” Whether or not it is possible logically to reconcile Sir Julian’s own account of his position, with the official definitions of it, the public will, I think, agree that it is the duty of the Committee of Imperial Defence, and of the Board of Admiralty, who are jointly responsible for the “ Official History,” to protect from aspersion the reputation of His Majesty’s officers.

The Prime Minister stated on 1st November that “ the preparation of the history is a charge on the Treasury Vote for the Committee of Imperial Defence, to whom Sir Julian Corbett is responsible as author " (Hansard, 1st November, 1920). The cost of the “ Official History,” therefore, is defrayed out of public money; and the public have the right to demand that the Committee of Imperial Defence should ensure accuracy and impartiality in official publications for which the Committee are responsible.

In the case under consideration, there is presented the curious anomaly of a narrative, the proofs of which were passed, “with a few suggestions,” by the Admiralty but of which the “tenour of the comments” contradicts the statement of the Admiralty, published by the Board on 30th August, 1914, and read to the House of Commons by the Parliamentary Secretary to the Admiralty on 12th March, 1919, that “the conduct and dispositions of Admiral Sir Berkeley Milne in regard to the German vessels Goeben and Breslau have been the subject of the careful examination of the Board of Admiralty, with the result that their Lordships have approved the measures taken by him in all respects.”

In what that conduct and those dispositions and measures consisted, it is my purpose to relate in the following pages.

II. THE SITUATION IN JULY 1914

AT the end of July 1914, the force under my command in the Mediterranean consisted of the three battle cruisers of the Second Battle Cruiser Squadron, the four armoured cruisers of the First Cruiser Squadron, commanded by Rear-Admiral С. T. Troubridge, four light cruisers and fourteen destroyers. [2]

[2] MEDITERRANEAN FLEET

Commander-in-Chief: Admiral Sir A. Berkeley Milne, Bt., G.C.V.O., K.C.B.; Chief of Staff: Commodore Richard F. Phillimore, C.B., M.V.O.

SECOND BATTLE CRUISER SQUADRON Inflexible (8-12*), flag of C.-in-C.

Captain Arthur N. Loxley.

Indefatigable (8-12*).

Captain Charles F. Sowerby.

Indomitable (8-12*).

Captain Francis W. Kennedy.

In order that the situation in the Mediterranean may be understood, it is necessary to indicate the relative strength in effective heavy ships of the other naval Powers in July 1914. France, shortly to become our Ally, possessed one Dreadnought, six " Dantons" and five other battleships.

FIRST CRUISER SQUADRON

Rear-Admiral С. T. Troubridge, C.B., C.M.G., M.V.O.

Defence (4-9-2*, 10-7-5*), flag of R.-A.

Captain Fawcet Wray.

Black Prince (6-9-2*, 10-6*).

Captain Frederick D. Gilpin-Brown.

Duke of Edinburgh (6-9-2*, 10-6*).

Captain Henry Blackett.

Warrior (6-9-2*, 4-7-5*).

Captain George H. Borrett.

LIGHT CRUISERS

Chatham (8-6*).

Captain Sidney R. Drury-Lowe.

Dublin (8-6*).

Captain John D. Kelly.

Gloucester (2-6*, 10-4*).

Captain W. A. Howard Kelly, M.V.O.

Weymouth (8-6*).

Captain William D. Church.

Austria-Hungary, a member of the Triple Alliance, possessed three Dreadnoughts and three other battleships. Italy, also a member at that time of the Triple Alliance, possessed three Dreadnoughts, and four other battleships. Germany had placed the Goeben, battle cruiser, and the Breslau, light cruiser, in the Mediterranean. In respect of heavy ships, therefore, the position was:—

France ... 12

Great Britain … 3

Total 15

Germany ... 1

Austria .... 6

Italy .... 7

Total 14

But a numerical comparison affords only a partial indication of the real position. Opposing navies are very seldom all in one place at one time. A squadron of one fleet may be attacked by the full strength of another fleet. France, if required to deal with Austria, might have been outnumbered by the accession of Italy. The three battle cruisers of Great Britain were liable to be hopelessly overwhelmed by either Austria or Italy.

At the end of July 1914, when war was expected, the possibility that both Austria and Italy would join Germany must be considered, and the instructions which I received from the Admiralty were framed in accordance with that contingency. Whether or not the possibility was considered that the Ottoman Empire would side with Germany, was not known to me. In June, I visited Constantinople in Inflexible. At that date, mines had already been laid in the Straits of the Dardanelles; and, in following the channel, we were brought within close range of the shore batteries.

In Constantinople, I was received with the greatest courtesy by the authorities, who did their utmost to make my visit pleasant. H.M. the Sultan honoured me, together with the officers of my staff, with an invitation to dine at Yildiz Kiosk, upon which occasion the Grand Vizier, and all the Ministers were present, except Enver Pasha, who was absent from Constantinople. I went to see the Royal stables and visited an Anatolian Cavalry Regiment. H.R.H. the Crown Prince came on board the flagship, H.M.S. Inflexible. His Royal Highness had not visited the Goeben, when, a few months before, Admiral Souchon’s flagship was at Constantinople. I mention these incidents of our reception, because (among others) they gave no suggestion of anti-English sympathies on the part of Turkish officials, but rather indicated most friendly feelings towards Great Britain.

I was asked to inspect the Turkish crew which was on the point of leaving to take over the battleship built in England for Turkey. They arrived in England, but their ship, together with another vessel also built for Turkey, was acquired by Great Britain. These deprivations probably exercised a considerable effect on Turkish opinion; for the ships had been built by subscription, and their arrival was eagerly expected by the Turkish Ministers, and especially by Djemal Pasha, Minister of Marine, who had intended to go to England and to return in one of the new vessels.

III. PRELIMINARY DISPOSITIONS

Such was the general situation in the Mediterranean when, on 27th July, 1914, I received from the Admiralty the preliminary telegram of warning. On that day, the greater part of the British Fleet was at Alexandria, in accordance with the cruising arrangements. At Alexandria were two battle cruisers, Inflexible (flag) and Indefatigable, two armoured cruisers, Warrior and Black Prince, four light cruisers and thirteen destroyers. Rear- Admiral Troubridge, flying his flag in the armoured cruiser Defence, with the destroyer Grampus, was at Durazzo in the Adriatic in accordance with Admiralty orders. There also were the French cruiser Edgar Quinet and the German light cruiser Breslau. These vessels represented the various Powers supporting the international conference then assembled at Scutari for the purpose of settling the affairs of Albania. The battle cruiser Indomitable was at Malta, where her annual refit had just begun, a point to remember in relation to the sequel. The armoured cruiser Duke of Edinburgh was also at Malta, where her annual refit had just been completed. The Goeben, flagship of Admiral Souchon, was then at the Austrian port of Pola, where she had been refitted, and the Breslau (as it has been said) was also in the Adriatic at Durazzo.

Immediately upon receiving the pre-liminary telegram of warning on 27th July, I sent instructions to the Admiral Superintendent at Malta to take all requisite precautions against attack. Ships at Malta were to be prepared for sea, coal and stores for the Fleet were to be in readiness. A telegram was sent to Rear-Admiral Troubridge at Durazzo to take all requisite precautions against attack. The Fleet sailed from Alexandria on the 28th July.

On 29th July the Fleet arrived at Malta. By the afternoon of Saturday, 1st August, the Fleet was in every respect ready for service.

Late in the evening of 29th July I received the warning telegram. On the same date the Admiralty recalled the Defence, flagship of Rear-Admiral Trou- bridge, and the Grampus from Durazzo to Malta. On 80th July, in accordance with Admiralty instructions, the P. and O. s.s. Osiris was ordered to bring British troops from Scutari to Malta. The Osiris was subsequently converted into an auxiliary cruiser.

At eight o’clock on the evening of 30th July, I received the telegram from the Admiralty indicating the political situation and containing my instructions. The communication is summarized in the “Official History of the War : Naval Operations,” by Sir Julian Corbett (Vol. I., p. 34), as follows :—

Admiral Sir Berkeley Milne " was informed of the general situation and what he was to do in the case of war. Italy would probably be neutral, but he (Admiral Milne) was not to get seriously engaged with the Austrian Fleet till her (Italy’s) attitude was declared.”

Sir Julian Corbett’s summary of my instructions is sufficiently accurate so far as it goes. The phrase “what he was to do in the case of war,” however, may not be clearly understood by the public. As Commander-in-Chief, I had in my possession written instructions given to me by the Admiralty. It was in the discretion of the Admiralty to direct me to proceed in accordance with those instructions, or to telegraph new orders varying them. In the event of my receiving no new orders, the written instructions stood. It is, of course, conceivable that circumstances might arise in which an Admiral’s judgment of what ought to be done would conflict with his orders. As the contingency did not, in fact, occur in my own case, there is no need to discuss the point. I wish to make it quite clear from the beginning that the question whether the dispositions ordered by the Admiralty would in all cases have been my dispositions had they been left to my discretion, does not arise.

Sir Julian Corbett proceeds as follows : “His (Admiral Sir Berkeley Milne’s) first task, he was told, should be to assist the French in transporting their African Army, and this he could do by taking up a covering position, and endeavouring to bring to action any fast German ship, particularly the Goeben, which might try to interfere with the operation. He was further told not to be brought to action in this stage against superior forces unless it was in a general engagement in which the French forces were taking part.”

Reference to the map of the Mediterranean will make clear the strategic position. In the Western Mediterranean the French Fleet was to protect the passage of the French African Army from the ports of Algeria to Toulon. In the Eastern Mediterranean were the Goeben and Breslau, immediately dangerous; the Austrian Fleet, a potential danger; and the Italian Fleet, doubtfully neutral. Between the Western and the Eastern Mediterranean open two gates; one, the narrow Strait of Messina, the other, the wide channel between Cape Bon on the African coast and Marsala in Sicily. Midway in the channel arc placed Malta, the headquarters of the British Fleet, and, further west, the Island of Pantellaria. The Fleet under my command, therefore, was placed between the French Fleet and hostile intervention from the Eastern sea. There were two Powers to consider, Austria and Italy; and two German ships to watch, one of which, the Goeben, was faster than any other vessel of the same class in the Mediterranean. For all purposes, the force at my disposal consisted of three battle cruisers, four armoured cruisers, four light cruisers and small craft.

On 31st July, I informed the Admiralty that I considered it necessary to concentrate all my available forces, and that I could not at first provide protection to trade in the Eastern Mediterranean. Sir Julian Corbett (“Official History,” I. 34), states with regard to my dispositions at this time: “Considering it unsafe to spread his cruisers for the protection of the trade routes, he contented himself with detaching a single light cruiser, the Chatham (Captain Drury-Lowe), to watch the south entrance of the Strait of Messina.” The obvious inference to be drawn from this passage is unfortunate. The disposition of cruisers was not a question of safe or unsafe, nor whether the Commander-in-Chief was “contented " or not. It was a question of strategic and tactical requirements, whose fulfilment was approved by the Board of Admiralty. Moreover, Sir Julian Corbett is in error in stating that the Chatham was despatched on 30th July. She did not leave Malta until 2nd August.

On 31st July, Defence (flag of Rear- Admiral) and Grampus arrived at Malta from Durazzo. On the same day, in accordance with Admiralty orders, the Black Prince was ordered to Marseilles to embark Earl Kitchener. The order was cancelled on 2nd August, and the Black Prince returned to Malta, arriving there on 3rd August.

On Saturday, 1st August, the Admiralty ordered the Examination Service to be put in force. Instructions were given to get the boom defence at Malta into position. By this date the whole Fleet was concentrated at Malta.

On Sunday, 2nd August, I received information that the Goeben had been coaling at Brindisi on the previous day. The Admiralty informed me that the situation was very critical. Later in the day I received from the Admiralty instructions summarized in the “Official History” (I. 85), as follows: “Then, in the afternoon, came further orders which overrode the disposition he had decided on. Informing him that Italy would probably remain neutral, the new instructions directed that he was to remain at Malta himself, but to detach two battle cruisers to shadow the Goeben, and he was also to watch the approaches to the Adriatic with his cruisers and destroyers.”

In accordance with these instructions, Rear-Admiral Troubridge left Malta the same evening with the battle cruisers Indomitable and Indefatigable, the three armoured cruisers, Defence, Warrior, Duke of Edinburgh, the light cruiser Gloucester, and eight destroyers.

The two battle cruisers were attached to the Rear-Admiral’s squadron in accordance with the Admiralty instructions " to detach two battle cruisers to shadow the Goeben.” The rest of the Rear-Admiral’s force, in accordance with the Admiralty instructions, was ordered to watch the mouth of the Adriatic. Thus Rear- Admiral Troubridge left Malta with two separate forces, each allotted to a particular purpose by the Admiralty. The light cruiser Chatham went to search for the German ships in the Strait of Messina. Four destroyers went to patrol the Malta Channel.

IV. THE FRENCH DISPOSITIONS

Upon the same evening, Sunday, 2nd August, I received permission from the Admiralty to communicate with the French Senior Officer. All attempts to communicate with him by wireless having failed, on the following (Monday) evening, I despatched the Dublin light cruiser to Bizerta with a letter addressed to the French Admiral. It will be observed that upon the very eve of war, it had proved impossible to make any arrangements with the French Naval Forces, with which I had been instructed to work, and hostile interference with which I had been instructed to prevent. It is stated in the “Official History " (I. 85), that " the fact was, there had been a delay in getting the fleet to sea. By the timetable of the war plan it should have been covering the Algerian coasts by August 1, but so anxious, it is said, were the French to avoid every chance of precipitating a conflict, that sailing orders were delayed till the last possible moment. . . . Whatever the real cause, it was not until daybreak on August 3rd that Admiral de Lapeyrere put to sea, with orders * to watch the German cruiser Goeben and protect the transport of the French African troops'."

But of these matters I was necessarily ignorant at the time. I knew nothing of the French naval dispositions, except that, in whatever they consisted, it was my duty to assist in protecting the transport of the French African Army. I was not informed of the dispositions of Admiral de Lapeyrere; I received no reply to wireless calls; and on Monday, 3rd August, I despatched the light cruiser Dublin to Bizerta, carrying a letter for the French Admiral at that port.

As the " Official History ” records, Admiral Воue de Lapeyrere put to sea on the same day at 4 a.m. The French Fleet was formed into three squadrons; the first consisting of six battleships of the Danton type, three armoured cruisers and a flotilla of twelve destroyers; the second consisting of six battleships, three armoured cruisers and a flotilla of twelve destroyers; the third consisting of four older battleships. Thus, for covering the passage of their African Army from Algeria to Toulon, there was provided a force of sixteen battleships, six armoured cruisers and twenty-four destroyers. At the moment it sailed from Toulon, “Germany had not yet declared war, the attitude of Italy remained doubtful, and it was quite unknown whether Great Britain would come into the war or not.” (“Official History,” I. 59.)

V. FIRST MEETING WITH GOEBEN AND BRESLAU

I NOW return to the events of Sunday, 2nd August. As already stated, on the evening of that day Rear-Admiral Troubridge sailed for the entrance to the Adriatic with two battle cruisers, three ships of the First Cruiser Squadron, the light cruiser Gloucester and eight destroyers; and later in the day I received information that the Goeben had been coaling at Brindisi.

At 5.12 p.m. the Chatham (Captain Sidney R. Drury-Lowe), had sailed from Malta with instructions to search for the Goeben in the Strait of Messina, and subsequently to join the Rear-Admiral’s squadron.

Four destroyers were patrolling the Malta Channel. My force at Malta was thus reduced to the battle cruiser Inflexible (flag), two light cruisers and small craft. According to Admiralty instructions, the Black Prince, then on her way to Marseilles to embark Earl Kitchener, was recalled to Malta, where she arrived early on Monday, 3rd August.

On Monday, 3rd August, at 4 a.m. I received further instructions from the Admiralty. These are described by Sir Julian Corbett (“Official History,” I. 54), as follows : “About 1 a.m. on August 3rd, to give further precision to their orders, the Admiralty directed that the watch on the mouth of the Adriatic was to be maintained, but that the Goeben was the main objective, and she was to be shadowed wherever she went.” Sir Julian Corbett’s comment on his version of the telegram is that, “Taking this as a repetition of the previous order which instructed him to remain near Malta himself, Admiral Milne stayed where he was and left the shadowing to Admiral Troubridge.” Here, again, the implication is inaccurate. Sir Julian Corbett implies that I was acting upon an assumption. Although, as he states, Sir Julian Corbett had access to all telegrams, and therefore he must have read my telegram to the Admiralty of the previous day (2nd August), Sir Julian Corbett neither mentions the telegram nor the fact that in the telegram I expressly submitted to their Lordships that my tactical dispositions required my remaining at Malta for the time being. The Admiralty reply of the following day was, therefore, both a definite confirmation of my proposed dispositions together with additional instructions concerning them; and I acted, not upon an assumption but, upon orders. |

These instructions were of the greatest moment. The significant clause was “... but Goeben is your objective.” That order clearly indicated that two immediate objects were to be pursued simultaneously: the watch upon Austria and Italy in the Adriatic, and the watch upon the Goeben; and that, of the two, the watch upon the Goeben was the more important. There were also to be fulfilled the earlier instructions : that I was to protect the transport of the French African Army, and to avoid being brought to action by superior forces. The order to protect the French transports was, in fact, covered by the order to watch Italy, Austria and the two German ships. The contingency of being confronted by superior forces, did it occur, must have involved the subordination of all other considerations, for the only way of avoiding action is to retreat.

At 4 a.m. on that Monday morning, 3rd August, I received the Admiralty instructions. At the same time, although I knew nothing of it, the French Fleet sailed from Toulon for the Algerian coast.

At 7 a.m., the Chatham reported that neither the Goeben nor the Breslau was in the Strait of Messina. At the same time I received information that Goeben and Breslau had been sighted early on the previous (Sunday) morning off Cape Trion, the southern horn of the Gulf of Taranto, heading south-west. It therefore appeared that the two German ships had escaped from the Adriatic. In order both to maintain the watch on the Adriatic and to find Goeben and Breslau, at about 8.30 a.m. I ordered Rear-Admiral Troubridge, whose squadron was then about midway between Cape Spartivento, Italy, and Cape Passero, Sicily, to send the light cruiser Gloucester and the eight destroyers to the mouth of the Adriatic, while the rest of his squadron was to pass south of Sicily and to the westward. The light cruiser Chatham was ordered to pass westward along the north coast of Sicily. The light cruisers Dublin and Weymouth were set to watch the Malta Channel. These dispositions were made in case the German ships should endeavour to pass westward, and they were reported to the Admiralty.

At 1.30 p.m. I made further dispositions. Rear-Admiral Troubridge was instructed to proceed to the mouth of the Adriatic with the First Cruiser Squadron to support the Gloucester and the destroyers there, and Black Prince was ordered to rejoin the Cruiser Squadron. The two battle cruisers Indomitable and Indefatigable were ordered to proceed through the Malta Channel and thence westward to search for Goeben, in accordance with the original Admiralty instructions allocating these two ships for that purpose. At the same time the Senior Naval Officer at Gibraltar was requested to keep a close watch for Goeben and Breslau in case they passed the Strait.

At 5 p.m., as I had failed to establish communication with the French either at Toulon or Bizerta, I despatched the light cruiser Dublin to Bizerta, with a letter to the French Admiral. I did not, of course, know that by that time the French Fleet, steaming at 12 knots, had been at sea for eleven hours. It appears that the British Admiralty were also ignorant of the sailing of the French Fleet, for it is stated in the “Official History" (I. 55), that “ organized connection between the British and French Admiralties had not yet been established.” The Admiralty were, therefore, anxious lest the two German ships should escape into the Atlantic. There was never the least suggestion that they might escape elsewhere. My own impression that the Germans would turn westward was confirmed by a report that a German collier was waiting at Majorca.

At 6.30 p.m. in Inflexible, I left Malta to take up a watching position in the Malta Channel, together with the light cruiser Weymouth, the torpedo-gunboat Hussar and three destroyers. At 8.30 p.m. I received instructions from the Admiralty to send two battle cruisers to Gibraltar at high speed to prevent the Goeben from leaving the Mediterranean. Indomitable and Indefatigable were already on their way westward, and they were ordered to proceed at 22 knots to Gibraltar. The Chatham, which was then rounding Sicily, and which had nothing to report, was ordered to Malta to coal.

On Tuesday, 4th August, then, the position was as follows : Inflexible (flag), with Weymouth and small craft, was patrolling the Malta Channel; Rear-Admiral Troubridge, with the First Cruiser Squadron, was about midway between Malta and the mouth of the Adriatic, on his way to reinforce the Gloucester and the destroyers; the light cruiser Dublin had gone to Bizerta, with a letter for the French Admiral; Chatham was coaling in Malta; and the two battle cruisers, Indomitable, Captain Francis W. Kennedy (in command). Indefatigable, Captain Charles F. Sowerby, were steaming westward at 22 knots.

Where were the Goeben and Breslau ? No one knew. At 7 a.m. on Monday, the Chatham had reported they were not in the Strait of Messina. It was now Tuesday. The fact was, they had passed the Strait during the night of Sunday 2nd—Monday 3rd, ahead of the Chatham.

At 8.30 a.m. on Tuesday, 4th August, I received information that Bona had been bombarded by the German ships.

At 9.32 a.m. Indomitable and Indefatigable, off Bona, on the Algerian coast, sighted the Goeben and Breslau, which were steering to the eastward.

"The Goeben was seen at once to alter course to port, and Captain Kennedy altered to starboard in order to close, but the Goeben promptly turned away, and in a few minutes the two ships were passing each other on opposite courses at 8,000 yards. Guns were kept trained fore and aft, but neither side saluted, and after passing, Captain Kennedy led round in a wide circle and proceeded to shadow the Goeben, with his two ships on either quarter. The Breslau made off to the northward and disappeared, and early in the afternoon could be heard calling up the Cagliari wireless stations.” (“Official History,” I. 57.)

Had a state of war then existed, it is probable there would have been a very different end to that meeting.

At 10.30 a.m. Dublin arrived at Bizerta, and at my orders she left at once to join Indomitable in shadowing the German ships, which were steering eastward, on a course lying north of the Sicilian coast, towards Messina. During the afternoon, Dublin joined Indomitable and Indefatigable at a point north of Bizerta. In the meantime, Goeben and Breslau, steaming at their utmost speed, were drawing away from the British battle cruisers, which presently lost sight of the German ships. The Dublin picked them up about 5 p.m., and kept them in sight until nearly 10 p.m., when she lost them off the Cape San Vito, on the north coast of Sicily, and turned back to rejoin the battle cruisers. The Goeben had recently been refitted at Pola, while Indomitable had only just been docked for repair when the warning telegram arrived.

During the day Inflexible (flag), with a division of destroyers, keeping within visual signaling distance of Castille (Malta), waited in the Malta Channel for information and instructions from the Admiralty. At 8.15 p.m., as already stated, I received information from the French Admiral at Bizerta that the Goeben had bombarded Bona and that the Breslau had bombarded Philippeville, on the Algerian coast. What had happened (as we now know), was that the German vessels, upon leaving Messina on the night of 2nd-3rd August, made a descent upon Bona and Philippeville in order to interfere with the transport of the Eastern Division of the French XLX-th Army Corps. According to the “Official History" (I. 55-56), Admiral Souchon, at 6 p.m. on the 3rd August, learned that war had been declared, but he received no orders until midnight, when he was instructed to proceed with Goeben and Breslau to Constantinople. “Long afterwards,” writes Sir Julian Corbett, " it became known that on the following day (4th August) the Kaiser informed the Greek Minister that an alliance had been concluded between Germany and Turkey, and that the German warships in the Mediterranean were to join the Turkish Fleet and act in concert.”

That is an affair of diplomacy upon which I make no comment. It is certain at least that I received no information of any such arrangement, nor, according to the “Official History,” had the British authorities any knowledge of that most momentous treaty. All that we knew in the Mediterranean was that the two German ships steered eastward on the 4th August. Germany was then at war with France, but not with England.

At 5 p.m. on 4th August, about the time when the two battle cruisers lost sight of the Goeben, I received authority from the Admiralty to engage the German vessels should they attack the French transports. The occasion did not arise, and the order was cancelled in the subsequent telegram received two hours later, informing me that the British ultimatum presented to Germany would expire at midnight.

VI. NEW DISPOSITIONS

Аt 6 p.m. on the same day, Tuesday, 4th August, I received a telegram from the Admiralty which seriously altered the strategic situation. I was informed that Italy had declared strict neutrality, which was to be rigidly respected, and that no ship of war was to pass within six miles of the Italian coast. The effect of the order was to bar the Strait of Messina, presumably to both belligerents, certainly to British ships. If the Goeben and Breslau entered the Strait, they could not be followed. They might break back westward or they might turn south through the Strait, and then either turn eastward to the Adriatic, or west through the channel between Africa and Sicily.

In these new circumstances I ordered Chatham and Weymouth to patrol the channels between the African coast and Pantellaria Island and between Pantellaria Island and the coast of Sicily, in case the German ships should turn south; while, further north, Indomitable and Indefatigable, and, later, Dublin patrolled between Sicily and Sardinia, in case the German ships should turn west again.

At 7 p.m. I received a telegram from the Admiralty informing me that the British ultimatum to Germany would expire at midnight, and that no acts of war should be committed before that hour.

It was now necessary to make new dispositions in accordance with my orders. The neutrality of Italy having been declared, I was relieved of responsibility with regard to the Italian Fleet. But it was still of course necessary to watch the Adriatic, both in case the German ships tried to enter that sea and in case the Austrian Fleet sailed. But my first duty was the protection of the French transports from the Goeben and the Breslau.

Now the Goeben had shown herself to be at least three knots faster than the British battle cruisers. The superiority in speed of the enemy necessarily governed all my dispositions. For the benefit of the lay reader it should here be explained that it is useless to try to overtake a ship which is faster than her pursuer. The chase merely continues until fuel is exhausted. Therefore, in order to catch a ship which is superior in speed to her pursuers, it is necessary that the faster ship should be intercepted by crossing her course. That maneuver was performed by Indomitable and Indefatigable on Tuesday, 4th August, when they were at one time within 8,000 yards of Goeben.

That pursuing ships must be so disposed as to cut off the faster ship pursued, is an elementary maxim in tactics which the author of the “Official History " strangely ignores.

In disposing my forces to prevent the Goeben and Breslau going westward, it was therefore necessary to arrange, not to chase but, to intercept, the enemy. At any moment the Germans might try to break westwards, in which case there were three courses open to them. They might (1) pass north of Corsica; or (2) through the Strait of Bonifacio between Corsica and Sardinia; or (8) south of Sardinia between Sardinia and the African coast. I considered that the German ships would avoid both the north of Corsica and the Strait of Bonifacio, for fear of French cruisers, destroyers and submarines. In all probability they would, therefore, try to pass south of Sardinia, and thence to Majorca, where a German collier was waiting at Palma.

In these circumstances, Rear-Admiral Troubridge was ordered, on Tuesday, 4th August, to detach Gloucester to watch the southern end of the Strait of Messina, into which, it will be remembered, British ships of war were forbidden to go. Rear- Admiral Troubridge, with four armoured cruisers and eight destroyers was to continue to watch the mouth of the Adriatic. The two battle cruisers (except Gloucester) and three destroyers were ordered to join my flag off Pantellaria Island at 11 a.m. on the following day, 5th August. These dispositions were communicated to the Admiralty at 8.30 pm. 4th August.

At fifteen minutes past one, 5th August, on the night of 4th-5th August, I received the order to commence hostilities against Germany. I was then in the Malta Channel, and left at once in Inflexible, with three destroyers. At about 11 a.m. on 5th August, Inflexible (flag), Indomitable, Indefatigable, Dublin, Weymouth, Chatham and three destroyers were assembled off Pantellaria Island, midway in the channel between the African coast and Sicily. Dublin was sent back to Malta, there to coal and thence to proceed with two destroyers to join Rear-Admiral Troubridge at the mouth of the Adriatic. Indomitable and three destroyers went into Bizerta to coal. Inflexible (flag) with Indefatigable, Chatham and Weymouth, patrolled on a line northward from Bizerta, being thus disposed to intercept the German ships should they attempt to escape westwards.

At 5 p.m. on Wednesday, 5th August, the German ships were reported to be coaling at Messina.

VII. THE “OFFICIAL " VERSION

It is at this point in the series of events, as related in the “Official History,” that the following comment is made by the official historian. After quoting from my despatch to the Admiralty, Sir Julian Corbett observes: “Nevertheless, he had left the line of attack from Messina open, but, apart from this serious defect in his dispositions, [3] they were in accordance with his original instructions. The order that the French transports were to be his first care had not been cancelled, though, in fact, there was now no need for him to concern himself with their safety.” (“ Official History,” I. 58.)

[3] My italics – A.B.M.

I do not propose to discuss my dispositions with Sir Julian Corbett; but I would observe that the official historian states that, in making them, I had departed from my original instructions, and that the result of that departure was a “serious defect.” I do not understand what Sir Julian means when he asserts that the line of attack from Messina was left open, nor does he explain his meaning. But I affirm that there was, in fact, no departure from my instructions; and that, as Sir Julian Corbett must be aware, my dispositions were approved by the Admiralty in all respects. Yet we have this extraordinary circumstance, that the Admiralty, having submitted to them Sir Julian Corbett’s statement, allowed it to be published, with what is virtually their approval.

Sir Julian adds that there was no longer any need for me to concern myself with the safety of the French transports. Here the implication is that I knew, and also that the Admiralty knew, the movements of the French Fleet, and that either my original instructions should have been cancelled, or that I should have disobeyed them. Here, again, the Admiralty allowed the publication of what is, in fact, a totally false implication; and which is indeed virtually contradicted by the historian himself; for, after interpolating a description of the rapid and unexpected changes in the disposition of the French naval forces, which were not understood at the time by the British authorities, and which were unknown to me, Sir Julian Corbett proceeds to remark that the reason for my own dispositions “ was clearly a belief that the Germans might still have an intention to attack the French convoys, and so long as this was a practical possibility, the Admiral could scarcely disregard his strict injunctions to protect them.” (“Official History,” I. 62.) The historian goes on to describe the position and the feelings of Admiral Souchon and the officers and men of the Goeben and Breslau, then coaling at Messina, adding, what is perfectly true, that “ all this was in the dark, when Admiral Milne, feeling bound by his instructions that the ‘ Goeben was his objective,’ made his last dispositions to prevent her escape to the northward.”

Sir Julian Corbett would seem to consider, as he certainly implies, that a flag-officer may obey or disobey, according to his fancy, the orders he receives from the Admiralty.

While such a misapprehension might naturally be entertained by a civilian, it cannot possibly exist at the Admiralty; and I am, therefore, at a loss to understand on what principle the Admiralty sanctioned the publication of these passages. The historian further implies that it was, in any case, a mistake to take measures to prevent the Goeben and Breslau from escaping “northward.” Again, that may be the opinion of Sir Julian Corbett; but, again, it cannot possibly be the opinion of the Admiralty, for their Lordships both ordered and subsequently approved that disposition of forces. It was a disposition which, at the time, I considered to be the best disposition, nor do I now perceive what in the circumstances would have been a better strategical distribution. Nor does Sir Julian Corbett suggest one.

VIII. GOEBEN AND BRESLAU AT MESSINA

I return to the sequence of the events of Wednesday, 5th August, when Inflexible (flag) with Indefatigable and Weymouth were patrolling the passage between the African coast and the south coast of Sicily. Indomitable and three destroyers had gone to Bizerta to coal. Chatham, which had captured a German collier, was ordered to take her into Bizerta and coal. Dublin was coaling at Malta, and was ordered to proceed thence with three destroyers to join the Rear-Admiral’s squadron at the mouth of the Adriatic. Gloucester was watching the southern end of the Strait of Messina.

At midday I received a report that the Austrian Battle Fleet was cruising outside Pola, in the Adriatic. It should be borne in mind that, at this time, the neutrality of Austria was in doubt.

At 2 p.m. I received a telegram from the Admiralty informing me that Austria- Hungary had not declared war against France or Great Britain and instructing me to continue to watch the mouth of the Adriatic, so that the Austrian Fleet should not emerge unobserved, and that the two German ships should be prevented from entering the Adriatic. It should here be remembered that the numerical and potential superiority of the Austrian Fleet over the British Fleet made the attitude of Austria of supreme moment, a point wholly ignored in the "Official History.”

At 5 p.m. (Wednesday, 5th August) I received a report from Gloucester that, judging by wireless signals intercepted, the Goeben appeared to be at Messina. It should here be mentioned that on the preceding day I had learned that the General, a German mail steamer, had landed passengers at Messina and was remaining at the disposition of the Goeben. It was probable, therefore, that Goeben, Breslau and General were all at Messina. A further report to the same effect was received a little later. At 7 p.m. I received information from the Admiralty that mines had been laid in the Dardanelles (they had been laid before I passed the Straits in June), and that the Dardanelles lights had been extinguished. Had there been any conjecture that the Goeben would try to pass the Dardanelles, it would have been weakened by the information that mines had been laid and lights extinguished. But, in fact, there was no such conjecture. According to the “Official History,” it seems that the German Admiral himself was in a state of painful irresolution.

“According to Admiral von Tirpitz, when on August 3 news was received of the alleged alliance with Turkey, orders were sent to Admiral Souchon to attempt to break through to the Dardanelles. On August 5 the German Embassy at Constantinople reported that, in view of the situation there, it was undesirable for the ships to arrive for the present. Thereupon the orders for the Dardanelles were cancelled, and Admiral Souchon, who was then coaling at Messina, was directed to proceed to Pola or else break into the Atlantic. Later in the day, however, Austria, in spite of the pressure that was being put upon her from Berlin to declare war, protested she was not in a position to help with her fleet. In these circumstances it was thought best to give Admiral Souchon liberty to decide for himself which line of escape to attempt, and he then chose the line of his first instructions.” (“Official History,” I. 71, note.) [4]

[4] According to Major Molas, private secretary to King Constantine of Greece, the existence of the treaty was known in Greece. “On 4th August, 1914, the Kaiser sent for our Minister at Berlin and told him that he might officially inform King Constantine that an alliance had been definitely concluded on that day between Germany and Turkey, and gave him to understand, moreover, that certainly Bulgaria, and perhaps Roumania, would range themselves on the side of the Central Powers.” (" Ex-King Constantine and the War.” George M. Milas. Hutchinson, 1920.)

If the account of Grand-Admiral von Tirpitz, cited by Sir Julian Corbett, be accurate, it will be observed that the whole situation turned upon the conclusion between Germany and Turkey of the secret treaty, which, according to Sir Julian Corbett, was not known to the British Government until “long afterwards.” Again assuming von Tirpitz’s account to be accurate, it would be interesting to learn what, in the view of Sir Julian Corbett—even if he had known on 5th August, 1914, the circumstances which he relates in his history, and which he states were unknown to the authorities—would have been the correct disposition of the British Fleet remedying the “serious defect ” he describes.

Having received no news of the German ships during the night of 5th-6th August, at 6.30 a.m. on Thursday, 6th August, proceeding upon the assumption that they were at Messina, I began a sweep to the eastward, north of Sicily, with Inflexible (flag), Indefatigable and Weymouth. If the Goeben, after coaling at Messina, had left the Strait by the north entrance, she would be signaled by my squadron at about 6 p.m. By 4.40 p.m. I had received no report of the departure of the Goeben from Messina. That she had not escaped westwards, I knew. She might have gone north, but, considering it improbable that she would take that course, I determined to close the northern entrance to the Strait of Messina. The squadron was disposed accordingly. Chatham was ordered to proceed at 20 knots to Milazzo Point, off Messina, and was informed of the position which would be occupied by the two battle cruisers and Weymouth at midnight.

These dispositions had scarcely been made when, half an hour later, the Gloucester, which was watching the southern entrance to the Strait, reported that the Goeben was coming out of the Strait of Messina, the Breslau following her one mile astern, steering eastward. The position was then as follows: If Goeben and Breslau attempted to enter the Adriatic, Rear-Admiral Troubridge, with the First Cruiser Squadron and ten destroyers, would prevent them; if the German ships, followed by Gloucester, escaped her in the night and turned westwards, my squadron of battle cruisers must be so placed as to intercept them. As my instructions strictly forbade me to enter the Strait of Messina, I was obliged, in order to take up the requisite position, to come down the west coast of Sicily. With Inflexible (flag), Indefatigable, Weymouth and Chatham (recalled) I accordingly proceeded to round the west coast of Sicily. Further reports from Gloucester, which was pursuing the German ships, stated that they were steering eastward, then north-eastward.

I therefore continued on my course to Malta, in order to coal there and to continue the chase, arriving at noon on Friday, 7th August. Chatham was then ordered to patrol off Milazzo, in case Goeben and Breslau should turn back and escape through the Strait of Messina northward.

In the meantime, at 11 p.m. on the night of Thursday, 6th August, I had received a telegram from the Admiralty countermanding previous instructions and ordering me, if the Goeben went south, to follow her through the Strait of Messina. Unfortunately, by the time the new instructions reached me, it was too late to fulfil them. I was then off Maritimo, the west coast of Sicily, and to return to Messina would have involved traversing two sides of a triangle, instead of the one which I had still to traverse, as a reference to the chart will show; or, as it stated in the "Official History ” : “Unfortunately, it (the telegram) did not come to hand till midnight, too late for the Admiral to modify the movement to which he was committed.” (I. 63.)

In the "Official History ” occurs the following account of the dispositions of the German ships, taken from Ludwig’s “ Die Fahrten der Goeben und der Breslau,” p. 55 :

“Admiral Souchon’s intention, as his one chance of escape, was to steer a false course until nightfall, so as to give the impression he was making back to join the Austrians in the Adriatic, and as his reserve ammunition had been sent to Pola, this was probably the original intention before the intervention of Great Britain rendered that sea nothing but a trap. The orders he issued were that the Goeben would leave at 5 p.m. at seventeen knots; the Breslau would follow five miles astern, closing up at dark; while the General, sailing two hours later, would keep along the Sicilian coast and make, by a southerly track, for Santorin, the most southerly island of the Archipelago. The two cruisers, after steering their false course till dark, would make for Cape Matapan (south of Greece), where, as we have seen, a collier had been ordered to meet them. In accordance with this plan, Admiral Souchon, the moment he sighted the Gloucester, altered course to port so as to keep along the coast of Calabria (Italy) outside the six-mile limit.” (“Official History,” I. 68.)

Sir Juhan Corbett, in preparing his material, had before him the orders of the German and French Admirals, as well as those of the British Admiral; he also knew the actual dispositions and movements from day to day, the objects with which they were made, and the actual results obtained. He seems, perhaps un-consciously, to ignore the fact that the orders and the dispositions of French and German ships were unknown at the time both to the Admiralty and to the British Commander-in-Chief.

For instance, Sir Julian Corbett, referring to my dispositions, proceeds to affirm that my "idea was that Admiral Troubridge, with his squadron and his eight destroyers, besides two more which were being hurried off to him from Malta in charge of the Dublin, was strong enough to bar the Adriatic, and that there was still a possibility of the German making back to the westward along the south ' of Sicily.” Here, again, the implication is clearly that my “idea” was mistaken; and again I have to observe that it was not a question of ideas, but of the best dispositions it was possible to make in the circumstances, dispositions which were demanded by the only known conditions of the problem, and which were approved at every stage by the Admiralty.

IX. SECOND MEETING WITH GOEBEN AND BRESLAU

To return to the chase of the Goeben and Breslau so gallantly conducted by Captain W. A. Howard Kelly in Gloucester. At 7.30 p.m. on Thursday, 6th August, the German ships were steering north-east along the coast of Calabria, between Gloucester and the land. As the dark fell, they were becoming lost to sight; and Captain Kelly, in order to keep them in view and to get them in the light of the moon, steered inshore to reverse the position. In so doing, he ran well within range of the Goeben, which could have sunk him, and proceeded on her port quarter. The Breslau then began to pinch him inshore, and Captain Kelly was obliged to drop back. The Breslau steered to cross his bows; Captain Kelly altered course to meet her; and the two ships passed each other at a distance of 4,000 yards. Captain Kelly, rightly considering it to be his first duty to follow the Goeben, did not open fire. Breslau retreated east-south-eastwards and disappeared. Captain Kelly held on in chase of Goeben. At about two o’clock the Goeben, then off the Gulf of Squillace, also altered course to the southward.

In the meantime, Rear-Admiral Troubridge, who had been patrolling with the First Cruiser Squadron (Defence (flag), Warrior, Duke of Edinburgh, Black Prince) off Cephalonia, on the west coast of Greece, upon learning that the German ships were steering north-eastward, went north, in order to engage them off Fano Island, should they attempt to enter the Adriatic. When he learned that the Goeben and Breslau had altered course to the southward, Rear-Admiral Troubridge, at midnight on the night of 6th-7th August, turned south to intercept them. In the " Official History " it is stated that "His intention had been to engage the Goeben if he could get contact before 6 a.m., since that was the only chance of his being able to engage her closely enough for any prospect of success, and when he found it impossible, he thought it his duty not to risk his squadron against an enemy who, by his superiority in speed and gun-power, could choose his distance and outrange him.”

At 4 a.m. on the morning of Friday, 7th August, I received information from Rear- Admiral Troubridge that he had abandoned the chase of the German ships; or, to be more exact, that he had abandoned his intention of intercepting them and bringing them to action.

For his conduct on this occasion Rear- Admiral Troubridge was tried by Court martial and was " fully and honorably " acquitted. [5]

[5] Sir Julian Corbett, on p. 67, quotes the verdict of the Court, thus suggesting that he had access to the records of the Court-martial, which was held in secret. Indeed, his whole account of the matter gives the same impression. The papers have been denied to Parliament.

There is, of course, nothing more to be said on the matter; and my observations upon the episode do not refer to Rear- Admiral Troubridge, but to the account of the episode presented in the “Official History.”

It is there stated that Rear-Admiral Troubridge "had received no authority to quit his position, nor any order to support the Gloucester " (I. 65). The statement is incorrect. On 3rd August, the Rear-Admiral had received the Admiralty instructions (already described) to maintain the watch on the Adriatic, and stating, " but Goeben is your objective.” Nor are the Rear-Admiral’s signals to me, to which Sir Julian Corbett presumably had access, in accordance with Sir Julian’s statement.

Sir Julian Corbett proceeds (I. 65) to make the following extraordinary statement : “Still, he (Rear-Admiral Troubridge) only slowed down, and held on as he was, in expectation that his two battle cruisers would now be sent back to him, with instructions for concerting action.”

I do not know why Sir Julian Corbett should attribute that action and that expectation to the Rear-Admiral. He did not, as the chart (No. 4) published in the “Official History” clearly shows, hold on “as he was,” but turned eastward to Zante. Nor is it possible to understand why the Rear-Admiral should be described as regarding the battle cruisers as “ his,” when they were no part of his command, and as expecting the arrival of ships which he knew were 800 miles away, a fact which Sir Julian Corbett could have ascertained had he consulted the Admiralty chart accompanying the text of his own “Official History.” Still less is it possible to understand why the Admiralty should have permitted the publication of these blunders.

A little further back in his account of the matter (I. 61), Sir Julian Corbett actually represents Rear-Admiral Troubridge as expecting on the previous Wednesday, 5th August, that “his two battle cruisers would now be returned to him ”when the Rear-Admiral, of course, knew that they were cruising north of Sicily. It has already been explained that the two battle cruisers were at first attached to the Rear-Admiral’s squadron for the sole purpose of shadowing the German ships. Then follows this remarkable passage, in which Rear-Admiral Troubridge is de-scribed as entertaining quite inexplicable ideas : “Indeed, his impression was that when they (the two battle cruisers) were first attached to his flag it was a preliminary step to the whole command devolving on him. For in the provisional conversations with France it was understood that the British squadron at the outbreak of war would come automatically under the French Commander-in-Chief— an arrangement which necessarily involved the withdrawal of an officer of Admiral Milne’s seniority.”

Sir Julian Corbett’s reason for attributing this singular view to the Rear-Admiral can only be conjectured. As a matter of fact, the arrangement between the French and British Governments to which he refers was not signed until 6th August, and I received no copy of it until my arrival at Malta on 10th August. Nor under that agreement was the command to pass to the French Admiral until the XIXth Army Corps had been landed in France. But, in any case, it is quite incredible that a flag-officer should be under the “impression " that any strategical dispositions were a “preliminary step to the whole command devolving on him,” in the absence of any notification to that effect. Rear-Admiral Troubridge, however, is in a position to defend himself against these charges. I mention them, because Sir Julian Corbett, assuming their accuracy, proceeds to imply that I ought to have acted in accordance with a state of things which did not, in fact, exist.

" Admiral Milne,” writes Sir Julian (I. 61), “ however, took an entirely different view, and still feeling bound by his “primary object,’ began at 7.30 a.m. on August 6 to sweep to the eastward, intending to be in the longitude of Cape San Vito, the north-west point of Sicily, by 6 p.m., ‘ at which hour,’ so he afterwards explained, ‘the Goeben could have been sighted if she had left Messina, where he considered she was probably coaling.”

The true sequence of events, as already narrated, sufficiently indicates the series of false implications contained in this passage. The main implication is, not only that I was mistaken in every particular, but that the Admiralty were also mistaken. If there is any other inference to be drawn from this part of Sir Julian Corbett’s “History,” it is that the forces operating to the north of Messina should have been withdrawn in defiance of all instructions, leaving that way of escape open to the Goeben.

At about the time (midnight, 6th-7th August) when Rear-Admiral Troubridge turned south from off Santa Mama to intercept the German ships, the Dublin and two destroyers, on the way to join the Rear-Admiral, sighted, in the moonlight, smoke on the horizon. Captain John Kelly, commanding Dublin, had been guided by signals received from his brother, Captain W. A. Howard Kelly, commanding Gloucester, then chasing the Goeben. At first Captain Kelly, in Dublin, took the ship in sight to be Goeben. Then the signals from Gloucester told him that she must be Breslau, and at 4 a.m. he altered course to attack Goeben by torpedo.

But Captain John Kelly failed to find Goeben, and continued on his course to join the Rear-Admiral’s flag. Captain Howard Kelly, in Gloucester, continued his pursuit of the Goeben. At about 5.80 a.m. (Friday, 7th August), I signaled to Captain Kelly instructing him gradually to drop astern and to avoid capture. Captain Kelly held on, and at 10.30 a.m. Breslau rejoined Goeben. At about 1 p.m., Breslau, in order to check Gloucester, began to drop astern. Captain Kelly, in order to keep Goeben in sight, determined to engage Breslau, so that either she would be forced to retreat towards Goeben, or Goeben would be compelled to turn back. At 1.85 he opened fire, which was returned. Captain Kelly increased speed, brought the enemy on his starboard quarter and continued fire, it is believed with effect. The maneuver had the result intended, for the Goeben turned 16 points and opened fire, whereupon Captain Kelly broke off the action, retreated, and then continued the chase until the German ships had rounded Cape Matapan. I had ordered Captain Kelly, who was, I knew, getting short of coal, and who ran great risk of capture, to stop pursuit at Cape Matapan and to rejoin the Rear-Admiral. At 4.40 p.m., then, Captain Kelly turned, while the German ships held on through the Cervi Channel, between the southern extremity of Greece and the island of Kithera. Captain Kelly was highly commended for his action by the Admiralty, and received the honour of the Companionship of the Bath.

During the night of 6th-7th August, I had received an offer from the French Admiral to place at my disposal a squadron of armoured cruisers.[6]

[6] Armoured cruisers Bruix, Latouche-Treville, Admiral Charner and cruiser Jurien de la Graviere.

X. FURTHER DISPOSITIONS

Аt noon on Friday, 7th August—while Gloucester was still pursuing Goeben—Inflexible (flag), Indefatigable and Weymouth arrived at Malta and coaled. Chatham was then patrolling north of Messina. Indomitable, which had been coaling at Bizerta, arrived at Malta shortly after the arrival there of the rest of my squadron.

In the “Official History " it is stated that " The Indomitable at Bizerta was greatly delayed in coaling, so that it was not until 7 p.m. she was ready to sail, and then she received her orders—but they were not that she should reinforce Admiral Troubridge.” (I. 61.) [7]

[7] The footnote on p. 61,1. “Official History,” referring to the coal supply at Bizerta, is inaccurate. The collier mentioned was sent in by me to supply the Fleet.

Here there is a clear implication on the part of the historian that the Indomitable should have been sent to reinforce the Rear-Admiral in the Adriatic. Again, on p. 66, it is stated that “The Indomitable was coming up astern at 21 knots, and when she reached Malta he (the Commander-in-Chief) did not send her on, but kept her there till his two other ships had coaled.” Sir Julian Corbett here distinctly implies that the Indomitable was kept at Malta without reason. The reasons, however, are contained in the documents to which Sir Julian Corbett had access. There were two reasons. One was that in pursuing the German ships at full speed on 4th August, there occurred boiler defects in Indomitable, which made it necessary to spend twelve hours in Malta in repairing them. The other reason was related to that superiority in speed possessed by the Goeben, which the official historian ignores. At noon on 7th August, when Indomitable arrived at Malta, Goeben was off the southern extremity of Greece, and proceeding eastwards. Had Indomitable (without repairing her boiler defects) been ordered to proceed direct from Bizerta, at the time of her leaving that port on the evening of 6th August, she would have been some 850 miles distant from Gloucester, and about 365 miles distant from the German ships. Goeben and Breslau were then steering towards the Adriatic, where Rear-Admiral Troubridge, with the First Cruiser Squadron was waiting for them. When, later in the evening, I learned that the German ships had turned south, it was necessary to prevent their return westward to attack the French transports. In order to do so, the battle cruiser squadron must be so disposed as to intercept the German ships. As already explained, owing to their superior speed, to attempt to catch them by pursuit was useless.

When upon the afternoon of 7th August, Goeben and Breslau entered the Cervi Channel, Indomitable would have been at least 180 miles distant from Goeben, and, supposing Goeben to continue to steam at only 15 knots, it would have taken Indomitable, steaming at 20 knots, another thirty-six hours to overhaul Goeben.

For these reasons, I considered it advisable to keep Indomitable with the rest of the Second Battle Cruiser Squadron, a decision which was approved by the Admiralty. But, apart from these considerations, had I sent Indomitable to chase Goeben, the sequel shows that the only result would have been to run her out of coal at a critical moment when the telegram notifying declaration of war against Austria having been received, it was necessary to concentrate the fleet.

With reference to the dispositions of Rear-Admiral Troubridge on the night of 6th-7th August, it is stated in the “Official History " (I. 64) that the Rear-Admiral’s “destroyers, with scarcely any coal in their bunkers, were all either at Santa Maura or patrolling outside. His intention, as we have seen, had been to seek an engagement only at dusk, but Admiral Milne had ordered him to leave a night action to his destroyers.” In a footnote it is added: “Their collier had been ordered to Port Vathi in Ithaca, but the Greek skipper had gone to another port of the same name.” It would be hard to pack more errors in the same number of words. The collier described as going to Port Vathi in Samos—not Ithaca—was the Greek vessel Petros, which several days later was taken up by the British Minister at Athens to carry 1,000 tons of coal from the Piraeus. The collier sent by me to supply the destroyers in the Adriatic was the Vesuvio, which left Malta at 8 p.m. on 6th August for Port Vathi, Ithaca — not Samos — where she duly arrived at 2 p.m. on the 8th. The Rear- Admiral was informed of her despatch, but he was evidently ignorant of her arrival, for he continued to report to me difficulties due to deficiency of coal. When, early on the 9th August, Weymouth visited Port Vathi, she found that the collier had arrived as arranged.

It is apparently the intention of the whole passage in the “Official History " referring to the lack of coal of the destroyers in the Adriatic, to suggest negligence on my part. The difficulty of obtaining coal was indeed considerable, and necessarily affected the disposition of forces, but not as implied in the “Official History.”

It may here be explained that at noon, on 7th August, I was informed by Rear-Admiral Troubridge that he was supplying destroyers with coal sufficient to enable them to steam to Malta at 15 knots. On the following day, 8th August (to anticipate a little the order of events), Gloucester reported that the second division of destroyers was kept at the Ionian Islands for want of coal, and in the evening the Rear- Admiral informed me that no destroyer had more than 40 tons. As it has been explained, the collier Vesuvio had already (2 p.m., 8th August) arrived at Port Vathi, Ithaca, unknown to the Rear-Admiral. By 9th August three more colliers were on their way to Port Vathi and an ample supply of coal was thus secured.

To return to the events of Friday, 7th August. At 8 p.m. three destroyers were sent to watch the southern end of the Strait of Messina, in case the German ships should return and attempt to pass the Strait. The patrol was maintained until 16th August. As the French squadron of armoured cruisers was patrolling the channel between Cape Bon, on the African coast, and Marsala in Sicily, both the westward lines of retreat were thus effectively watched.

At midnight a report was received that the German mail steamer General, after transformation into an armed auxiliary cruiser, had left Messina steering south. The French Admiral at Bizerta and all his ships were informed of the report.

XI. THE MISTAKEN TELEGRAM

BEFORE 1 a.m. on the morning of Saturday, 8th August, the Second Battle Cruiser Squadron, Inflexible (flag), Indomitable and Indefatigable, and Weymouth having completed with coal, sailed from Malta to search for Goeben and Breslau, which had been last seen by Gloucester, at 5.12 p.m. on the previous evening, steering east at 15 knots through the Cervi Channel, between Cape Malea, the southern extremity of Greece, and the Island of Kithera. At 8.37 a.m., 8th August, information was received that no German ships were at Naples. At 9.15 a.m. Chatham, patrolling to the north of Messina, was ordered to proceed southward through the Strait of Messina at 20 knots to Malta, there to coal.

Then occurred an incident which necessarily affected the whole of my dispositions, with the result that the pursuit of the German vessels was checked for twenty- four hours. The actual delay was much longer, as will appear, because the alteration of dispositions involved a considerable divergence of course and a consequent retracing of track.

In the "Official History " the account of the matter is as follows : “Then fortune played another trick, for here he received from the Admiralty a warning, which had been sent out by mistake, that hostilities had commenced against Austria. He could not yet tell whether the Goeben's objective might not be Alexandria and our Levant and Eastern trade, but since his last news of the French Fleet was that it would not be free to co-operate with him before the 10th, his only course seemed to be to turn back and re-concentrate his fleet. [8]

[8] My italics.—А. В. M.

“He therefore proceeded to a position 100 miles south-westward of Cephalonia so as to prevent the Austrians cutting him off from his base, and ordered Admiral Trou-bridge to join him. The Gloucester and the destroyers were to do the same, while the Dublin and Weymouth were left to watch the Adriatic. Later on in the day (August 8) he was informed that the alarm was false, but as, at the same time, he was instructed that relations with Austria were critical, he continued his movement for concentration till noon on the 9th. Then came a telegram from the Admiralty to say definitely we were not at war with Austria and that he was to resume the chase.” (I. 69).

The official historian here implies that in making the new dispositions, inaccurately described as “turning back,” there was a choice of courses to be followed. There was, in fact, no such choice. My written instructions concerning measures to be taken in case of war with Austria were explicit and definite. Either Sir Julian Corbett, in compiling his narrative, had access to copies of those instructions, or he had not. If he had access to them, I am at a loss to understand why he should imply that there was an alternative course, or that any considerations other than my instructions could possibly affect my action. If Sir Julian Corbett did not see my instructions, it is equally difficult to understand why he should have drawn conclusions for which he had no warrant, and why the Admiralty, which were aware of the facts, should have allowed those conclusions to pass.

What actually happened was that at 2 p.m. on Saturday, 8th August, when the squadron was half-way between Sicily and Greece, steering eastward, I received a telegram ordering hostilities against Austria to be begun at once. Acting instantly upon the instructions provided for that contingency, I proceeded to a position in which I could support Rear-Admiral Troubridge’s squadron, then watching the mouth of the Adriatic, and issued orders concentrating the Fleet.

In order to execute these dispositions, it was necessary to turn north-westwards, and to steer for a rendezvous 100 miles south-west of Cephalonia, at which the Rear-Admiral was ordered to join my flag. Weymouth was sent to join Dublin at the mouth of the Adriatic, and Chatham was ordered to join them so soon as she had finished coaling at Malta. Gloucester was ordered to convoy destroyers. Thus, at the critical moment of the search for the German vessels, the whole of the light cruiser force was diverted northwards from the line of pursuit.

At 4 p.m., a telegram was received from the Admiralty negativing the previous telegram. The new message being made in a somewhat irregular manner, it could not be accepted as genuine without confirmation, which was accordingly requested. The reply, received at 6 p.m., confirmed the negative telegram. A little later, in a further telegram from the Admiralty, the situation with regard to Austria was described as critical. In these circumstances, it was my duty to continue to act upon my instructions relating to the contingency of war with Austria. It is enough to say, as the “ Official History " correctly states, that those instructions involved the concentration of the Fleet and consequently the entire abandonment of the pursuit of the German vessels.