Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

SMALL UNIT ACTIONS DURING THE

GERMAN CAMPAIGN

IN

RUSSIA

by General-Major Burkhart Mueiler-Hillebrand, General-Major Heilmuth Reinhardt, and others

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY PAMPHLET NO. 20-269

FOREWORD

Department of the Army Pamphlet No. 20-269, Small Unit Actions During the German Campaign in Russia, is published as an adjunct to existing training literature in the belief that much can be learned from other armies, particularly the vanquished. It does not embody official training doctrine. Although called a historical study, it is not such according to a precise interpretation of the term. It is rather a series of interesting and instructive small unit actions based on the personal experience of Germans who actually took part in them.

Clausewitz wrote that, in the art of war, experience is worth more than all philosophical truth. This pamphlet is published with that thought in mind, tempered with the truth that investigation, observation, and analysis are necessary to give full meaning to experience.

ORLANDO WARD

Major General, USA Chief, Military History

WASHINGTON, D. C.

JANUARY 1953

PREFACE

The purpose of this text is to provide small unit commanders with instructional material, at their own level, concerning the Russian front during World War II. A careful study of the examples in the text will provide many lessons in tactics, logistics, and techniques, in the coordination of weapons, in the influence of terrain, climatic and weather conditions upon operations, and in the qualities of the officers and men who fought on the Russian front. It is only by utilizing German experience that the best insight into the fighting on that front can be secured.

To the average military student a thorough and detailed knowledge of the fighting and living conditions on the battlefield is of far greater benefit than a superficial acquaintance with large operations, which are primarily the province of commanders and staffs of the higher commands. In his Battle Studies, Ardant du Picq stated the same idea as follows:

The smallest detail, taken from an actual incident in war, is more instructive for me, a soldier, than all the Thiers and Jominis in the world. They speak, no doubt, for the heads of states and armies but they never show me what I wish to know—a battalion, a company, a squad, in action.

The young officer, lacking practical wartime experience, will find much information in field manuals and service regulations, but such texts will not stimulate his imagination or understanding of battle. These must be stimulated and developed by other means, if the principles propounded in manuals are to become a live part in the professional preparation of small unit commanders before they participate in battle. One of the most vivid media of instruction that can be drawn from military history is the small unit action based on personal experience.

A number of books dealing with small unit actions have been published. One of the first was Freytag-Loringhoven's Das Exerzier Reglement fur die Infanterie, which appeared in 1908 and which attempted to show the validity of selected statements in the German field manual for Infantry by subjecting them to the test of military history. Perhaps best known to the United States Army is Infantry in Battle, which considerably influenced U.S. Army training during the 1930's. During World War II General George C. Marshall, who as commandant of the Infantry School fathered Infantry in Battle, initiated the American Forces in Action. Series. These pamphlets are essentially small unit actions. Three Battles: Arnaville, Altmzo, and Schmidt is a volume in the official histories of THE UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR II and deals with small unit actions. Additional books of this type, soon to appear, are Service Goes Forward and Small Unit Actions in Korea.

The actions contained herein describe the Russian soldier, his equipment, and his combat methods under a variety of circumstances and conditions as seen by his opponent—the German. The narratives are intended to supplement the theoretical knowledge of Russian combat doctrine during World War II that can be acquired from the study of manuals. Whereas the military doctrines of the nations vary little, the application of these doctrines differs greatly between countries. The chief characteristics of Russian combat methods during World War II were the savagery, fanaticism, and toughness of the individual soldier and the lavish prodigality with human life by the Soviet high command.

The actions here described are based solely on German source material, primarily in the form of narratives of personal experience. They were written under the direct supervision of General Franz Haider, Chief of the German Army General Staff from 1938 to 1942. General Haider, like many of our own high-ranking officers, has on numerous occasions expressed interest in small unit actions and has often stressed their importance in training junior leaders.

The German narratives, comprising over a hundred small unit actions, reached this Office in the form of 1,850 pages of draft translations done in the Historical Division, USAREUR. These wTere analyzed for content, presentation, and pertinence to the subject. The better ones were then rewritten, edited, and arranged in chronological sequence to give the best possible coverage to the different phases of the German campaign in Russia. Under the direction of Lt. Col. M. C. Heifers, Chief of the Foreign Studies Branch, Special Studies Division, Office of the Chief of Military History, this work, as well as the preparation of maps, was done by Mr. George E. Blau, Chief, and 1st Lt. Roger W. Reed, 1st Lt. Gerd Haber, Mr. Charles J. Smith, and Mr. George W. Garand of the Writing and Translation Section. Although the original German source material has undergone considerable revision, every effort has been made to retain the point of view, the expression, and even the prejudices of the original.

P. M. ROBINETT

Brigadier General, U. S.A. Ret.

Chief, Special Studies Division

[Most of the illustrations are from the collection of captured German combat paintings now in the custody of the Chief of Military History, Special Staff, U.S. Army; the others are U.S. Army photos from captured German films.]

Map 1 . GENERAL REFERENCE MAP OF EUROPEAN RUSSIA

PART ONE. INTRODUCTION

I. General

Proper combat training for officers and enlisted personnel is essential to military victory. The objective of peacetime training must be to improve their efficiency so that they can achieve optimum performance in time of war. This will be attained if every soldier knows how to handle his weapon and is fully integrated into his unit and if every leader is able to master any situation with which he might be faced. The better their preparation for war, the fewer improvisations commanders and soldiers will have to introduce in combat.

Every tactician and instructor recognizes the validity of these principles and tries to instill them in his trainees in the most realistic manner. Yet even the best-trained German troops had to learn many new tricks when war broke out and when they were shifted from one theater to another. In each instance they were faced with problems for which they were not sufficiently prepared. In unusual situations field commanders were sometimes compelled to violate certain regulations before they could be rescinded or modified by higher authority.

The preceding observations give an indication of the problems involved in preparing the German field forces for an encounter with an opponent whose pattern of behavior and thinking was so fundamentally different from their own that it was often beyond comprehension. Moreover, the peculiarities of the Russian theater were such that German unit commanders were faced with situations for which there seemed to be no solution. The unorthodox Russian tactics with which the Germans were not familiar were equally disturbing, and Russian deception and trickery caused many German casualties. Several months of acclimatization were often necessary before a unit transferred to Russia was equal to the demands of the new theater. Occasionally a combat efficient unit without previous experience in Russia failed completely or suffered heavy losses in accomplishing a difficult mission that presented no problems to another unit familiar with the Russian theater, even though the latter had been depleted by previous engagements. This fact alone proved how necessary it was to disseminate the lessons learned in Russia, since this was the only method by which inexperienced troops could be spared the reverses and heavy casualties they would otherwise suffer during their commitment against Russian troops. To meet this need for training literature, a series of pamphlets a*:ci instructions based on German combat 3xperiences in Russia was issued in 1943-44.

II. The Russian Soldier

The Germans found, however, that to be acquainted with Russian tactics and organization was useful but by no means decisive in achieving victory in battle. Far more important was the proper understanding of the Russian soldier's psyche, a process involving the analysis of his natural impulses and reactions in different situations. Only thus were the Germans able to anticipate Russian behavior in a given situation and draw the necessary conclusions for their own course of action. Any analysis of the outstanding characteristics of the Russian soldier must begin with his innate qualities.

a. Character. The Slav psyche—especially where it is under more or less pronounced Asiatic influences—covers a wide range in which fanatic conviction, extreme bravery, and cruelty bordering on bestial ity are coupled with childlike kindliness and susceptibility to sudden

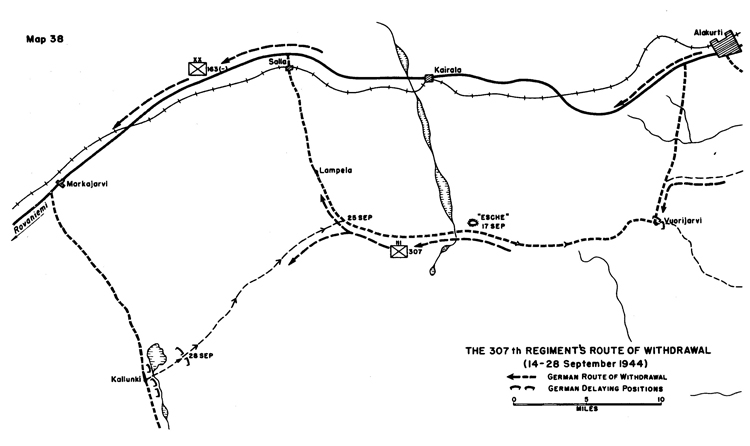

fear and terror. His fatalistic attitude enables the Russian to bear extreme hardship and privation. He can suffer without succumbing.

At times the Russian soldier displayed so much physical and moral fortitude that he had to be considered a first-rate fighter. On the other hand, he was by no means immune to the terrors of a battle of attrition with its combination of massed fire, bombs, and flame throwers. Whenever he was unprepared for their impact, these weapons of destruction had a long-lasting effect. In some instances, when he was dealt a severe, well-timed blow, a mass reaction of fear and terror would throw him and his comrades completely off balance.

b. Kinship With Nature. The Russian soldier's kinship with nature was particularly pronounced. As a child of nature the Russian instinctively knew how to take advantage of every opportunity nature offered. He was inured to cold, hot, and wet weather. With animal-like instinct he was able to find cover and adapt himself to any terrain. Darkness, fog, and snowdrifts were no handicap to him.

Even under enemy fire he skillfully dug a foxhole and disappeared underground without any visible effort. He used his axe with great dexterity, felling trees, building shelters, blockhouses, and bunkers, and constructing bridges across waterways or corduroy roads through swamps and mud. Working in any weather, he accomplished each job with an instinctive urge to find protection against the effect of modern weapons of destruction.

c. Frugality. The frugality of the Russian soldier was beyond German comprehension. The average rifleman was able to hold out for days without hot food, prepared rations, bread, or tobacco. At such times he subsisted on wild berries or the bark of trees. His personal equipment consisted of a small field bag, an overcoat, and occasionally one blanket which had to suffice even in severe winter weather. Since he traveled so light, he was extremely mobile and did not depend on the arrival of rations and personal equipment during the course of operations.

d. Physical Fitness. From the outset of the Russian campaign the German tactical superiority was partly compensated for by the greater physical fitness of Russian officers and men. During the first winter, for instance, the German Army High Command noticed to its grave concern that the Russians had no intention of digging in and allowing operations to stagnate along fixed fronts. The lack of shelter failed to deter the Russians from besieging German strong points by day and night, even though the temperature had dropped to —40° F. Officers, commissars, and men were exposed to subzero temperatures for many days without relief.

The essentially healthy Russian soldier with his high standard of physical fitness was capable of superior physical courage in combat.' Moreover, in line with the materialistic concepts of communism, the life of a human being.meant little to a Russian leader. Man had been converted into a commodity, measured exclusively in terms of quantity and capability.

III. German Adjustments to the Russian Theater of War

Conversely, the German troops were ill prepared for a prolonged campaign in Russia. An immediate readjustment and a radical departure from the norms established in the western and central European theaters of war became necessary. As a first adjustment to local conditions the German Army revised the standards for selecting lower echelon commanders. Their average age was lowered and the physical fitness requirements were raised. Staff cars, riding horses, and every piece of excess baggage had to be left behind whenever a German unit had to go into action against Russian forces. For weeks at a time officers and men had no opportunity to change their underwear. This required another type of adjustment to the Russian way of life, if only to prevail in the struggle against filth and vermin. Many officers and men of the older age groups broke down or became sick and had to be replaced by younger men.

In comparison with the Russian soldier, his German counterpart was much too spoiled. Even before World War I there was a standing joke that the German Army horses would be unable to survive a single night in the open. The German soldier of World War II had become so accustomed to barracks with central heating and running water, to beds with mattresses, and to dormitories with parquet floors that the adjustment to the extremely primitive conditions in Russia was far from easy. To provide a certain amount of comfort during a term of service extending over several years was perfectly justifiable, but the German Army had gone much too far in this respect.

The breakdown of the supply system and the shortage of adequate clothing during the winter of 1941-42 were the direct outgrowth of German unpreparedness. The extraordinary physical fitness of the Russians, which permitted them to continue the struggle without let-up throughout the biting-cold winter, caused innumerable German casualties and thereby shook the confidence of the troops.

IV. Peculiarities of Russian Combat Methods

During the course of the war the Russians patterned their tactics more and more after those of the Germans. By the time they started their major counteroffensives, their methods of executing meticulously planned attacks, organizing strong fire support, and establishing defensive systems showed definite traces of German influence. The one feature distinguishing their operations throughout the war was their total disregard for the value of human life that found expression in the employment of mass formations, even for local attacks. Two other characteristics peculiar to the combat methods of the Russians were their refusal to abandon territorial gains and their ability to improvise in any situation.

Infantry, frequently mounted on tanks and in trucks, at times even without weapons, was driven forward wave upon wave regardless of the casualties involved. These tactics of mass assault played havoc with the nerves of the German defense forces and were reflected in their expenditure of ammunition. The Russians were not satisfied at merely being able to dominate an area with heavy weapons or tanks; it had to be occupied by infantry. Even when as many as 80 men out of 100 became casualties, the remaining 20 would hold the ground they had finally gained whenever the Germans failed to mop up the area immediately. In such situations the speed with which the Russian infantry dug in and the skill with which the command reinforced such decimated units and moved up heavy weapons were exemplary.

A quick grasp of the situation and instantaneous reaction to it were needed to exploit any moment of weakness that was bound to develop even after a Russian attack had met with initial success. This was equally true in the case of a successful German attack. Under the impression that they had thoroughly beaten and shattered their Russian opponents during an all-day battle, the Germans occasionally relaxed and left the followup operation or pursuit for the next morning. On every such occasion they paid dearly for underestimating their adversary.

The conduct of the Russian troops in the interim periods between major engagements deserved careful analysis because it provided clues to what had to be expected during the initial phase of the coming battle. The gathering of information was complicated by the fact that Russian commanders put so much stress on concealing their plans during the buildup phase for an attack and during the preparation of a defensive system. The effectiveness of secrecy and adaptation to terrain was forcefully demonstrated in the shifting and regrouping of forces. While the speed with which Russian commanders effected an improvised regrouping of large formations was in itself a remarkable achievement, the skill with which individual soldiers moved within a zone of attack or from one zone to another occasionally seemed unbelievable. To see a few soldiers moving about in the snow at great distance often meant little to a careless and superficial observer. However, constant observation and an accurate head count often revealed surprisingly quick changes in the enemy situation.

In view of the alertness of the Russian infantryman and the heavily mined outpost area of his positions, a hastily prepared reconnaissance in force by the Germans usually failed to produce the desired results. Under favorable circumstances the patrol returned with a single prisoner who either belonged to some service unit or was altogether uninformed. The Russian command maintained tight security, and the individual soldier rarely knew his unit's intentions. The resulting lack of information with regard to Russian offensive plans gave no assurance, however, that strong Russian forces would not launch an attack at the same point the very next day.

To celebrate major Soviet holidays Russian sharpshooters usually tried to break the standing marksmanship scores and on those occasions German soldiers had to be particularly on the alert. In general, however, Russian attacks were likely to take place on any day, at any time, over any terrain, and under any weather conditions. These attacks derived their effectiveness mainly from the achievement and exploitation of surprise, toward which end the Russians employed infiltration tactics along stationary fronts as well as during mobile operations. The Russians were masters at penetrating the German lines without visible preparation or major fire support and at airlanding or infiltrating individual squads, platoons, or companies without arousing suspicion. By taking advantage of the hours of darkness, or the noon rest period, the weather conditions and terrain, or a feint attack at another point, the Russian soldiers could infiltrate a German position or outflank it. They swam rivers, stalked through forests, scaled cliffs, wore civilian clothing or enemy uniforms, infiltrated German march columns—in short, suddenly they were there! Only through immediate counteraction could they be repelled or annihilated. Whenever the Germans were unable to organize a successful counterthrust, the infiltrating Russians entrenched themselves firmly and received reinforcements within a few hours." It was like a small flame that rapidly turns into a conflagration. Despite complete encirclement Russian units which had infiltrated German positions could hold out for days, even though they suffered many privations. By holding out, they could tie down strong German forces and form a jumpoff base for future operations.

V. Russian Combat Orders

In contrast to the steady stream of propaganda poured out by the political commissars whose language abounded in flowery phrases and picturesque expressions designed to stimulate the Russian soldier's morale and patriotism, the combat orders of lower-echelon commanders were very simple. A few lines drawn on a sketch or on one of their excellent 1:50,000 maps indicated the friendly and hostile positions, and an arrow or an underscored place name spelled out the mission. As a rule such details as coordination with heavy weapons, tanks, artillery, tactical air support, or service units were missing, because more often than not the mission had to be accomplished without such assistance.

On the other hand, it would be unjust not to mention that these details were considered with utmost care by the intermediate and particularly by the higher echelon command staffs. Whereas in the early stages of the campaign captured Russian division and regimental orders often showed a tendency toward stereotype thinking and excessive attention to detail, during the later phases the Russian staff work improved considerably in this respect.

PART TWO. ARMS AND SERVICES

Chapter 1. Infantry

I. General

Hitler's plans for the invasion of Russia called for the destruction of the bulk of the Russian Army in western European Russia. A rapid pursuit was then to be launched up to a line extending approximately from the Volga to Archangel. Along this line, Asiatic Russia was to be screened from the European Continent by the German Army.

The execution of the operation was to be entrusted to three army groups. Army Group Center was to rout the Russian forces in White Russia and then pivot northward to annihilate the armies stationed in the Baltic area. This objective was to be achieved in conjunction with Army Group North which was to thrust from East Prussia in the general direction of Leningrad. Meanwhile, Army Group South was to attempt a double envelopment south of the Pripyat Marshes and crush the Russian formations defending the Ukraine before they could withdraw across the Dnepr. Here, Kiev was to be the first major objective, the seizure of the highly industrialized Donets Basin the next one. Once the northern and southern wings had made sufficient progress, all efforts were to be concentrated on the capture of Moscow, whose political and economic importance was fully recognized. The entire campaign was to be over before winter; the collapse of the Soviet Government was anticipated at an early stage of the campaign.

The description of the course of the actual operations is not within the scope of this study. However, knowledge of the planning on which the invasion was based does afford a better understanding of the series of actions involving Company G of a German infantry battalion during the crucial winter of 1941-42. This unit helped to guard the life lines of the two German armies holding the Vyazma-Rzhev salient west of Moscow (sees. Ill, IV, and VI-VIII).

The infantry actions included in this chapter stress fighting under poor weather conditions, particularly in subzero temperatures, in the

heart of European Russia. It was under such adverse conditions, which hampered armored operations, that German infantry battalions and companies demonstrated their capabilities and combat efficiency. A series of five other actions describes the struggle of the 2d Battalion of a German infantry regiment that fought to the bitter end in the Stalingrad pocket during the winter of 1942-43 (sees. IX-XII and XIV). The remaining examples have been selected to complete the picture of German and Russian small infantry units fighting under unusual weather and terrain conditions.

II. German Limited-Objective Attacks South of Leningrad (September 1941)

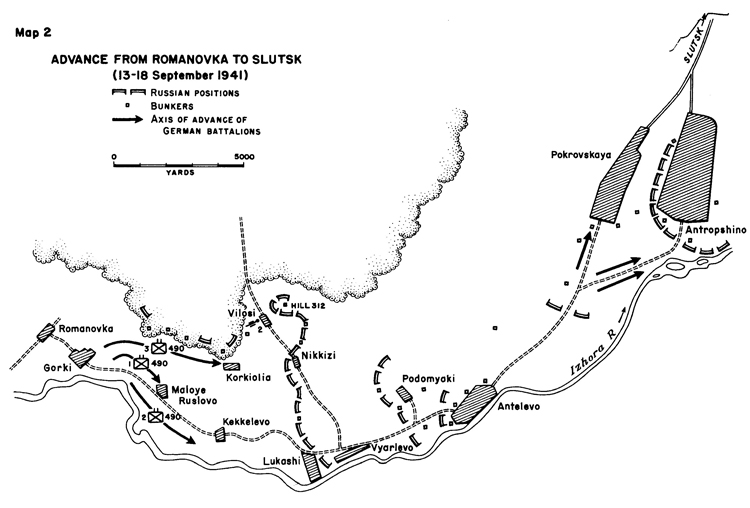

After its lightning advance through the Baltic States during the early days of the Russian campaign Army Group North arrived at the gates of Leningrad, where the Russians fiercely contested every inch of ground. During the late summer of 1941 the Germans were slowly forging a ring of steel around the strongly fortified city. In mid-September the 490th Infantry Regiment was given the mission of eliminating Russian centers of resistance approximately 15 miles south of Leningrad in the area north of the Izhora River between Romanovka and Slutsk. In the path of the regiment's advance stood an unknown number of Russian bunkers and defense positions established on the hills dominating the Izhora Valley. These positions had to be neutralized in order to secure the German lines of communication during the thrust on Slutsk. Late on 13 September the regiment crossed the river south of Gorki and spent the night in that village. The attack against the Russian-held hills north of the river was to start the next day, with the 1st and 2d Battalions advancing along the river valley and the 3d protecting the flank to the north (map 2).

Very little was known about either the terrain or the Russian fortifications in the area. The German maps, as well as previously captured enemy maps, were either inadequate or inaccurate. For this reason, the commander of the 3d Battalion decided to conduct careful terrain reconnaissance before attacking. The reconnaissance took the entire morning, and it was not until noon that the attack of the 3d Battalion against the Russian bunkers sast of Gorki finally got under way. Attached to the forward elements were three demolition teams equipped with flame throwers and shaped charges. Only a few minutes were required to dispose of the first Russian bunker. While the engineers were preparing to attack the next bunker, two Russian howitzers in a cornfield west of Vilosi went into action.

Map 2. ADVANCE FROM ROMANOVKA TO SLUTSK (13-18 September 1941)

The regimental artillery was on the alert and destroyed the two howitzers and a neafby ammunition dump. By 1600 the demolition teams had captured the second bunker and were preparing to attack a third, which they presumed to be the last. Half an hour later this bunker was in German hands. The engineers were just about to withdraw and take a well-deserved rest when the 1st Battalion advancing farther to the south, discovered two additional bunkers, one of which was about 1,000 yards southwest of Vilosi. The demolition teams destroyed both bunkers in short order, thus paving the way for the 3d Battalion's advance toward Hill 312 northeast of Vilosi. Continuing its attack, the 3d Battalion made some slight gains in the late afternoon of 14 September, but halted at 2015 after darkness set in and withdrew to Vilosi for the night. The other two battalions had made only little headway during the day, and spent the night of 14-15 September at the eastern edge of Vyarlevo. During the night Russian aircraft scattered bombs over widely separated areas, including some positions held by their own troops.

The seizure of strongly fortified Hill 312, scheduled for the next day, promised to be an arduous task. Although H-hour had originally been set for 0600, the attack had to be postponed until afternoon because the morning hours were needed for thorough terrain reconnaissance by two patrols sent out by the 3d Battalion.

One of the patrols, led by Lieutenant Thomsen, was to reconnoiter the hills between Korkiolia and Lukashi to determine whether and in what strength they were occupied by the Russians. The second patrol, under Sergeant Ewald, was to reconnoiter the area north of Hill 312 to determine the enemy's disposition and strength, and to probe for weak spots in his defense.

Patrol Thomsen was stealthily advancing southeastward from Korkiolia when it was suddenly intercepted and pinned down. In the ensuing exchange of fire the patrol was able to identify a number of Russian bunkers and field positions and to relay the necessary target data to the 3d Battalion CP. A short time later these Russian strong points were destroyed by the accurate fire of the regimental artillery. After having completed its mission, Patrol Thomsen returned to battalion headquarters.

By noon no word from Patrol Ewald had been received by the commander of the 3d Battalion. Since he could not postpone the attack on Hill 312 any longer, he ordered Lieutenant Hahn, the commander of Company I, to seize the hill.

GERMAN PATROL returning with prisoners and wounded comrades.

At 1230 Hahn assembled the assault force, which consisted of Company I plus a machinegun and a mortar platoon, a demolition team consisting of two engineers equipped with flame throwers and shaped charges, ancUen artillery observer. Since Sergeant Ewald's patrol had not returned, only the two platoons led by Lieutenant Borgwardt and Sergeant Timm were available for the attack. In extended formation, the assault force advanced through the woods west and northwest of Vilosi and reached a point north of Hill 312 apparently without attracting the enemy's attention. From there, Lieutenant Hahn identified a bunker on top of Hill 312 and two positions on its northern slope. The fortifications were held in strength. Before he was able to conclude his observations, the enemy spotted the Germans, fired on them, and pinned them down.

The artillery observer attached to the assault force called for direct howitzer fire, whereupon the bunker received two hits which, however, appeared to do little damage. Hahn reported the situation to battalion headquarters and was ordered to continue the attack.

Platoons Borgwardt and Timm were to skirt Hill 312 and approach its base through the dense thicket that extended southward from the forest edge to the hill. Platoon Borgwardt went to the right, Platoon Timm to the left. The latter was to support Borg-wardt's advance up the hill and then dispose of the obstinate bunker on the crest of the hill as soon as Borgwardt entered the two slope positions. While the two platoons were moving out, the attached machinegun and mortar platoons went into position at the edge of the forest north of Hill 312. The howitzers gave the signal to attack by firing six rounds at the enemy bunker on top of Hill 312. Company headquarters personnel had to act as covering force since an enemy relief thrust was to be expected at any time.

Again the fire of the howitzers failed to put the bunker out of action. While the shells were exploding on and around the bunker, Borg-wardt's men stealthily worked their way up the hill, creeping toward the two Russian positions whose occupants' attention was diverted by machinegun and mortar fire from the edge of the woods north of the hill. Platoon Borgwardt suddenly broke into the positions and caught the Russians completely by surprise.

While Borgwardt's men were engaged in seizing the two positions, Platoon Timm followed them up the hill and captured the bunker with the help of the engineers, whose flame throwers and shaped charges succeeded where the artillery had failed. Just as the operation seemed to have been brought to a successful conclusion, the personnel who had remained at the edge of the forest north of Hill 312 were attacked from behind by a force of about 50 Russians. Hahn ordered the newly arrived Patrol Ewald to hold off the Russians while

the rest of the assault force followed the elements that had captured the hill. Upon arriving at the summit they immediately set up their weapons, took the Russians under effective fire, and repulsed their attack. From the top of the hill, Hahn saw the 1st Battalion, now no longer subject to flanking fire from Hill 312, penetrate the Russian positions west of Nikkizi. He immediately established contact with the battalion commander and made preparations to defend the hill against a potential Russian counterattack. This precaution had to be taken, for within the hour the artillery observer on top of the hill noticed Russian forces assembling for a counterattack in the woods north and northeast of Hill 312. However, the Russians lost all enthusiasm for an attack after the German artillery lobbed a few well-aimed shells into their midst.

After the capture of the hill on the afternoon of 15 September, the 3d Battalion continued its advance on the left of the 490th Infantry Regiment. Russian resistance was light, and the battalion had little difficulty in occupying Podomyaki since the Russians had evacuated the fortified position west of the village and had withdrawn to Antelevo.

On the morning of 17 September the 3d Battalion prepared to advance from the northwest toward Antelevo, which the Russians appeared to be defending its strength. The Russian positions west and north of the village were situated on high ground dominating the terrain over which the battalion had to advance; to the south and east Antelevo was protected by the Izhora River. At dawn a reconnaissance patrol of Company I identified two concrete bunkers as well as field emplacements in and around Antelevo. The northern and western sections of the village were held by one Russian battalion. German howitzers and antitank guns took the bunkers under fire, though only with little effect. Once again demolition teams were needed to destroy the enemy fortifications with shaped charges. The flame throwers, which previously had proved so effective, could no longer be used since the supply of flame-thrower fuel had been exhausted.

By an unexpected stroke of luck, the reconnaissance patrol managed to capture a Russian outpost whose telephone was still connected to the CP of the Russian regimental commander at Antelevo. The German battalion commander immediately interrogated the captured Russian telephone operator and obtained the latter's code name. His next step was to put his knowledge of Russian to the test. Using the code name of the Russian telephone operator, he called the Russian regimental commander. The latter was apparently misled, but did not divulge anything of value except that he was determined to hold Antelevo.

When the German officer became more insistent in his quest for additional information, the suspicions of the Russian commander were aroused, and he changed his tone. The German then tried a more direct approach and made an outright demand for the surrender of the Russian regiment at Antelevo. This was curtly rejected.

The commander of the 490th Infantry Regiment thereupon decided to mass his forces and seize Antelevo by direct assault. During the afternoon of 17 September he assembled the 1st and 3d Battalions west and north of the village, respectively, and launched an attack against the enemy stronghold after a strong artillery preparation. Again the demolition teams performed their task in an exemplary manner and quickly put one Russian bunker after another out of action. The Russians had apparently considered these particular bunkers impregnable, for once they were destroyed the enemy infantry fled in wild disorder, abandoning most of its equipment. By nightfall Antelevo was securely in German hands.

With the fall of Antelevo, Russian resistance seemed to disintegrate all along the regiment's route of advance, except for a brief encounter at the road fork south of Antropshino. There the Russians attempted to stop the regiment along prepared positions, but failed to do so. After this delay the German forces fanned out and reached Slutsk on 18 September, the 3d Battalion via Pokrovskaya and the 1st and 2d via Antropshino. Upon its arrival in Slutsk the regiment established contact with the 121st Infantry Division, which had previously captured the town.

A number of lessons may be learned from this operation. First, all regimental units had to conduct thorough terrain reconnaissance since their maps and those captured from the Russians were frequently either inadequate or inaccurate. Whenever one of the battalion commanders failed to reconnoiter the terrain thoroughly, his unit was in danger of being ambushed by the Russians.

The Germans were able to take the Russian bunkers with a minimum loss of time and men by employing skilled demolition teams. Each member of these teams had been thoroughly trained and was well versed in his task.

The capture of the Russian outpost on the morning of 17 September might have provided the Germans with information about Russian intentions and troop dispositions, had it been properly exploited. The battalion commander showed a lack of good judgment by using his average knowledge of Russian in an attempt to extract information from the Russian regimental commander. This was clearly a task for an expert interpreter who was skilled in methods of interrogation.

The Russians were fighting a delaying action during which they often failed to take advantage of the favorable terrain and of their prepared positions. The flight of the Antelevo garrison was indicative of how easily the Russians became demoralized when they were confronted by an unexpected situation. When the German demolition teams blew up the bunkers with shaped charges, the Russians panicked and instinctively took to flight, as happened so often during the early months of the campaign.

III. Company G Counterattacks During a Snowstorm (November 1941)

This action is typical of the fighting in the late autumn of 1941, when Russian resistance began to stiffen west of Moscow and the ill-equipped German troops had to rally all their energy to continue the advance toward the Russian capital.

In November 1941 the 464th Infantry Regiment of the German 253d Infantry Division was occupying field fortifications about 60 miles northeast of Rzhev. On the regiment's right flank was Hill 747 (map 3). Since the hill afforded an extensive view of the German rear area, the Russians had made repeated attempts to capture it in an effort to undermine the position of the 464th Infantry Regiment. The hill had changed hands several times, but was now occupied by the Germans. The presence of heavy weapons including assault guns, as well as reports of repeated reconnaissance thrusts, gave rise to the belief that the Russians were preparing for another attack against the hill. Accordingly, the regimental commander withdrew Company G from the sector it was holding and committed it on the regiment's right flank.

After reporting to battalion headquarters around noon on 15 November, Lieutenant Viehmann, the commander of Company G, accompanied by his platoon leaders, undertook a terrain reconnaissance. A heavy snowfall set in. As the group was returning from the reconnaissance mission, submachine gun and mortar fire was heard from the direction of Hill 747. The company commander attached little importance to this at the time. However, upon arriving at the battalion CP he learned that the Russians had taken advantage of the snowstorm and had seized the hill without artillery or mortar support in a surprise raid. An immediate counterattack by German troops failed to dislodge the Russians.

Map 3. HILL 747 NORTHEAST OF RZHEV (15 November 1941)

Viehmann thereupon received orders to recapture the hill in a surprise attack to be launched at 2200. Regimental headquarters attached a medium mortar platoon and a light howitzer platoon to the company and promised artillery support. Viehmann formed three assault parties and moved them into jumpoff positions close to the Russian line under cover of darkness. The infantry company to the right was to divert the attention of the defending force at the time of the actual attack, while the unit to the left was to support the attack with its fire. Artillery and heavy weapons were to open fire on specified areas at prearranged flare signals.

The German assault parties occupied their jumpoff positions without attracting the * attention of the defending Russians. The party in the center, led by Viehmann, was only about 35 yards from the nearest Russian position. Close observation of the Russian defenses and the actions of individual soldiers indicated that a German attack was not anticipated. The Russian sentries were shivering from the cold and were by no means alert. Rations and supplies were being drawn. Not far from Viehmann's observation point a Russian detail was unloading furs and felt boots from a sled.

At 2200 the German assault parties, shouting loudly, broke into the Russian position. The attack confused the Russians, who dropped everything and attempted to make their way to the rear. Their escape, however, was prevented by the two assault parties that, at the beginning of the attack, had skirted either side of the hill and severed the Russian lines of communications. Unaware of the fighting, the Russian heavy weapons and artillery remained silent throughout the attack. When the signal flare went up, the German artillery and heavy weapons opened fire, laying a barrage on the Russian-held side of the hill. Two Russian machineguns covering each flank put up fierce resistance before being silenced in the hand-to-hand fighting.

GERMAN SENTRY using large wash tab to protect himself against icy wind.

After 45 minutes Hill 747 was completely in the hands of the Germans; their former MLR had been reoccupied and communications established with adjacent units. About 60 prisoners, 7 medium mortars, 5 heavy machineguns, 3 antitank guns, and large quantities of ammunition were taken. In the morning 70 Russian dead were found on the hill. Of the five German casualties, only one was severely wounded.

The manner in which the Russians exploited the snowstorm in carrying out a surprise attack without artillery or mortar support was typical of Russian infantry combat methods in wintertime.

The Russians launched their attack before winter clothing had been issued; some of the men wore only thin summer uniforms. As a stimulant, each Russian soldier was issued five tablets which had an effect similar to that of alcohol and a large ration of sugar cubes. In addition, the men were promised a special liquor ration upon completion of their mission. The sugar and tablets were presumably issued to counteract the discomfort caused by the temperature of 16° F. However, once the effects of these stimulants wore off, the men began to feel the cold acutely and their senses became numbed, as was observed in the case of the Russian sentries. During the German assault to retake Hill 747 the Russian defenders appeared to be as susceptible to the cold as were the Germans. This must be considered an isolated case, however, since the Russian soldiers were generally able to endure extremely low temperature. At the same time it indicates that some of the Russian units were insufficiently prepared for winter combat and had to improvise protective measures to overcome the rigors of the unexpectedly early winter weather.

IV. Company G Operates in Deep Snow (January 1942)

On 13 January Company G of the 464th Infantry Regiment was ordered to provide protection against Russian partisan raids on the division's supply line, which led from Toropets via Village M to Village O (map 4). To this end the company was reinforced by two heavy machineguns, two 80-mm. mortars, and one antitank platoon.

Map 4. FIGHTING EAST OF TOROPETS (13-16 January 1942)

On the evening of 14 January the company, mounted in trucks, reached Village O, 5 miles east of Village M. Upon its arrival at Village O, a supply unit, which was fleeing eastward toward Rzhev before the powerful Russian offensive, indicated that strong contingents of Russian troops from the north had cut the German supply route in the forest west of Village N. Using civilian labor, the Russians had constructed a road at least 30 miles long that led south through the large forest bypassing Toropets to the east. The company commander, Lieutenant Viehmann, decided to establish local security in Village O, spend the night there, and continue westward on foot the next morning in order to see what was going on. During the night a few Russian civilians slipped out of the village, established contact with the Russian troops, and supplied them with intelligence regarding the German dispositions.

At dawn on 15 January, after posting security details, the company started out and arrived in Village M without having made contact with the Russian's. As the company's advance element approached Village N, the Germans noticed a large group of soldiers in German uniform standing in the road, beckoning to them. That these soldiers were not Germans became evident when the antitank gun moving up behind the advance element was suddenly fired upon. The company's other antitank guns covered the advance element's withdrawal to Village M, where it rejoined the main body of the company. The prime mover of the lead gun was lost during this action. The Russians, however, did not follow up their attack.

In Village M the company set up hasty defenses against an attack from the north and west and tried to determine the strength and intentions of the opposing Russian force. From a vantage point in Village M it was possible to observe the eastern edge of Village N, where the Russians were building snow positions and moving four antitank guns into position. There was an exchange of fire but no indication of an impending Russian attack. During the hours of darkness Company G built snow positions along the western and northern edges of Village M, while the aforementioned supply unit occupied Village R, about one mile east of Village M, and took measures to secure it, particularly from the north.

During the night of 15-16 January reconnaissance patrols reported that the Russians were continuing their defensive preparations in Village N and that their line of communications was the road leading north from there.

On 16 January between 0400 and 0500 a 50-man Russian reconnaissance patrol approached the northwest corner of Village M on skis. Although the Russian patrol had been detected, it was allowed to come very close before it was taken under fire. Approximately 10 men of the patrol escaped and three were taken prisoner; the rest were killed before they could reach thwGerman position.

According to the statements of the three prisoners, two Russian divisions were moving south toward Village M. On 16 January Villages M and R were to be captured. What the prisoners either did not know or refused to tell, was that the Russians, attacking in force across frozen Lake Volga, had broken through the German positions west of the 253d Infantry Division 2 days before and had pushed on to the south. Thus, Viehmann was unaware of the true German situation.

Since the Russians in Village N remained passive, Viehmann decided to concentrate on defending his village against an attack from the north. The deep snow caused some difficulties; for instance, ma-chineguns had to be mounted on antiaircraft tripods so that a satisfactory field of fire could be obtained.

About 0800 on 16 January the company's observation post identified three Russian columns moving south toward the forest north of Village M. Except for antitank guns these columns did not seem to be equipped with heavy weapons. Around 1000 the first Russians appeared at the southern edge of the forest, some 1,000 yards from the German defensive positions. At 1020 the Russian center and right-wing columns attacked with antitank guns and infantry. Just a short time before this attack Company G had dispatched two rifle squads to Village R to reinforce the supply unit'there, since the Russian left-wing column was headed in that direction.

The first wave of Russian infantry, some 400 men strong, emerged from the forest on a broad front. It was evident that the 3-foot snow was causing them, great difficulty. The concentrated fire of the German heavy weapons succeeded in halting the attack after it had advanced about 200 yards.

After a short while a second, equally large wave emerged from the forest. It advanced in the tracks of the first and carried the attack forward, over and beyond the line of dead. The Russian antitank fire became heavier, being directed against the German machinegun positions, which the Russians had spotted. As a result, several ma-chineguns were destroyed; some changed their positions frequently in an effort to dodge the Russian fire. The Russians advanced an additional 200 yards, then bogged down under the effective German small arms fire. They sustained heavy losses which, however, were compensated for by the reinforcements pouring down south into the forest from Village P. Viehmann estimated that the Russians committed the equivalent of two regiments in this action.

By 1100 the Russian left-wing column had reached a point 150 yards from the German positions in Village R, where the terrain was more favorable for the attacker than that north of Village M. The supply unit and the two rifle squads defending Village R could no longer be reinforced because the road from Village M was under constant Russian fire.

Realizing that his position would become untenable within the next few hours, Viehmann ordered his men to prepare to evacuate Village M. A few men with minor wounds were detailed to trample a path through the deep snow from Village M toward the forest to the south in order to facilitate a quick withdrawal. The troops in Village R were also to withdraw to the same forest if pressed too heavily by the Russians.

The members of the third Russian assault wave emerged from the forest unarmed. However, they armed themselves quickly with the weapons of their fallen comrades and continued the attack. Meanwhile, Village R was taken and the Russians closed in on Village M from the east. The Germans were now very low on ammunition, having expended almost 20,000 rounds during the fighting.

About 1300 Company G, after destroying its mortars and antitank guns, evacuated Village M. Viehmann planned to make contact with the German troops in Village O by withdrawing through the forest south of Village M. He ordered the evacuation of the wounded, then withdrew with the main body of the company, and left behind a light machinegun and an antitank gun to provide covering fire and to simulate the presence of a larger force. After the gun crews had expended all the ammunition, they destroyed the breech operating mechanism of the antitank gun and withdrew toward the forest. About halfway there they were fired on by the Russians who had meanwhile entered Village M. The retreating Germans managed to escape without losses because the Russians did not pursue them into the forest.

During the next 3 days the company marched—with almost no halts for rest—through the deep snow that blanketed the dense forest, relying heavily on a compass in the absence of familiar landmarks. On 19 January, after bypassing Village O, which was found to be occupied by the Russians, it finally reestablished contact with the 253d Infantry Division. Only then did the company learn that all forces on the German front south of and parallel to Lake Volga had been withdrawn in the meantime.

In this action deep snow hampered the movements of both the attacking Russians and the defending Germans. Only by trampling a path in the snow before its withdrawal from Village M, did Company G avoid being trapped by the Russians.

GERMAN SENTRY in sheepskin coat near Moscow, December 1941.

The appearance of a Russian reconnaissance patrol in German uniform was a frequent occurrence; however, the number of disguised

Russians encountered on 15 January in Village N was unusually large. As so often happened during the winter of 1941-42, the Russians attacked in several waves on a given front, each successive wave passing over the dead of the preceding and carrying the attack forward to a point where it, too, was destroyed. Some waves started out unarmed and recovered the weapons from their fallen comrades.

V. Russian Infantry Attacks a German-Held Town (January 1942)

While the German troops west of Moscow tried to weather the Russian winter offensive and maintain their precarious lines of communication in the Rzhev-Velikiye Luki area, Marshal Timoshenko's forces launched a strong attack against Army Group South. In mid-January 1942 they attacked the German positions along the Donets River between Kharkov and Slavyansk and achieved a deep penetration near Izyum. The Russians smashed through the weakly held German positions and advanced westward, attempting simultaneously to widen the gap by attacking southward. In that direction the Russian objectives were Slavyansk and the industrial Donets Basin, whose capture would lead to the collapse of the German front in southern Russia.

The German troops along the Donets River had not expected^ Russian winter offensive since the opposing forces were believed to oe weak and incapable of launching one. Because of the shortage of winter equipment, the Germans had been forced to leave only outposts along the Donets River and in isolated villages, while their main forces occupied winter quarters far to the rear. In most instances the defending units were unable to delay the progress of the Russian offensive because the attacking troops simply bypassed them.

Toward the end of January the temperature dropped to — 50° F. The snow was about 3 feet deep. The weather was clear and a biting east wind prevailed.

There was light Russian air activity, with fighters and light bombers intervening occasionally in the ground fighting. The Lufwaffe rarely made an appearance.

Timoshenko's forces were at full combat strength, well armed, appropriately equipped for winter combat, and fed adequate rations. By contrast, the German units were at 65 percent of T/O strength and short of winter clothing and equipment, but their rations were plentiful.

Map 5. OEFENSE OF KHRISTISHCHE (23- 27 January 1942)

By defending the town of Khristishehe against attacks from the north, northeast, and east, the 1st Battalion of the German 196th Infantry Regiment was to block any further Russian advance along the road to Slavyansk (map 5). To the south, reconnaissance patrols were to maintain contact with a few strong points located in nearby villages. To the west the battalion was to keep in close contact with the adjacent unit of its regiment. Snow positions had been established at the edges of Khristishehe because it was impossible to dig in the frozen soil. The battalion's field of fire extended up to 2,200 yards north and south. To the east lay a long ridge, beyond which there was a large forest held by strong Russian forces.

During the night of 23-24 January a Siberian rifle regiment with twenty-four 76.5-mm. guns, advancing westward, reached a point 1 mile northeast of Khristishche. It fired on a German reconnaissance patrol, which withdrew southwestward leaving behind one wounded man, who disclosed to the Russians that there were two German regiments in and around Khristishche.

On the morning of 24 January a Russian reconnaissance patrol in platoon strength attempted to approach Khristishche, but was almost completely wiped out by German machinegun fire and snipers. Russian reconnaissance patrols looking down from the hill observed lively movement in the town, but made no attempt to advance any farther during daytime.

According to information obtained from a subsequently captured Russian officer, the Siberian rifle regiment received the following order on 24 January:

The Germans have been beaten along the entire front. They still cling to isolated villages to retard the victorious Russian advance.

Khristishche is being defended by severely mauled German units, whose morale is low. They must be destroyed so that the Russian advance to Slavyansk can continue.

At 2115 on 24 January two battalions of the regiment will attack Khristishche without artillery preparation and will advance to the western edge of the town. The 3d Battalion will follow behind the 1st and 2d Battalions and clear the village of all Germans. Then the 3d Battalion will occupy the nbrtheastern edge of Khristishche on both sides of the road leading to Izyum, facing southeast. Reconnaissance patrols will probe in the direction of Slavyansk. One ski company* will reinforce each assault battalion. The ski units will enter Khristishche without permitting anything to divert them from this objective. During the day preceding the attack the battalion and regimental artillery and mortars will fire for adjustment on all important targets. However, the Germans must not be led to expect our attack.

Throughout 24 January the positions of the 1st Battalion of the German 196th Infantry Regiment were hit by intermittent fire from light artillery and heavy mortars. Apparently this fire was directed by Russian observers on the ridge northeast of Khristishche.

At dusk the Germans increased their vigilance. In the snow trenches the sentries, dressed in white parkas, were doubled and posted at intervals of approximately thirty feet. Observation was made very difficult by the east wind, which blew snow into the men's faces. The sentries were relieved every 30 minutes.

T/0 & E of a Russian Ski Company

At 2115 the sentries of Company C observed rapidly approaching figures near the boundary between their sector and that of Company B. They tried to open fire with their machineguns but found them frozen. Finally, one sentry was able to give the alarm by firing his carbine. By this time Russian assault troops on skis had been observed along the entire battalion front firing carbines and signal pistols and throwing hand grenades. The only German machinegun which would fire was the one that had been kept indoors.

The Russian surprise raid did not proceed as planned because the attackers were unable to jump over the 4-foot snow wall on skis and because most of them were not immediately ready to fire since they carried their weapons slung across their backs. The Russians were therefore repulsed, except for those who penetrated into the extreme north end of the town. Twenty-five Russians occupied the first house but were wiped out within 5 minutes by hand grenades.

Meanwhile, the German mortars and infantry howitzers laid down a barrage on the ridge northeast of the town. Two Russian battalions, which had just gained the ridge, were caught in the barrage and turned back.

The 1st Battalion took 43 prisoners, including some wounded. Over a hundred Russians lay dead in and around the German positions. The Germans had lost 2 dead, 8 wounded, and 3 suffering from frostbite.

Throughout the night the Germans heard loud cries and shouting from the forest, followed by submachinegun and rifle fire. Russian prisoners subsequently stated that the commissars assigned to the platoons and companies were trying to reorganize their units. They were unsuccessful in this attempt until the following morning (25 January), by which time several Russian soldiers had been shot and the regimental commander replaced.

That same morning a Russian combat patrol of GO men approached Khristishche from the north but was wiped out some 500 yards from the German positions. In the afternoon two Russian reconnaissance patrols of 30 men each, supported by 3 machine gunners and 20 snipers, advanced toward the town from the southeast in single file. They were stopped halfway to their objective by German small arms fire. Approximately 20 men ran back over the hill, only to be stopped by their commissars and shot for cowardice. The intervening hours before darkness passed without incident.

The Russian troops built snow positions at the edge of the forest, set up observation posts and combat outposts on the crest of the hill, and dug emplacements for their artillery and mortars. Each squad built a shelter hut with tree trunks and branches, on top of which snow was packed. These shelters were built close together in an irregular pattern. The infantry howitzers and heavy mortars received five extra issues of ammunition, which were stored in nearby shelters.

That night a Russian combat patrol of 50 men under the command of an officer approached Khristishche from the east. The patrol was armed with 8 submachineguns, 2 pistols, 2 signal pistols, 38 automatic rifles, 2 light machineguns, each with 500 rounds of tracer ammunition, and 8 hand grenades per man. Most of the men wore padded winter uniforms and felt boots with leather soles; those, however, who could speak German were dressed in German uniforms. The patrol was to occupy the first houses and then send a message to the rear, where a reinforced company was kept in readiness to follow up the patrol's attack and to occupy Khristishche.

About 0130, while an icy east wind was blowing, five figures approached the two German sentries near the eastern corner of the town and called out from a distance, "Hello, 477th Regiment! Hello, comrades !" The Germans, who because of the whirling snow could see only about 60 feet ahead, challenged them from a distance of 30 feet with "Halt! Password!" The answer was "Don't fire! We are German comrades!" They continued to advance. The sentries now noticed a number of men about 50 feet behind the 5 soldiers who were approaching. Again they called "Password, or we fire!" Again the answer was "Don't shoot! We are German comrades!" Meanwhile the 5 Russians in German uniforms had approached to within 20 feet, whereupon they hurled hand grenades, which wounded 1 German sentry. The other fired his carbine to give the alarm, but in doing so was shot by the Russians, who immediately headed for the first house, followed by the main body of the combat patrol.

The Russians tossed hand grenades into the first house just as the men of the German squad which occupied the building ran out the back door without suffering any casualties. Throwing hand grenades and firing carbines and machineguns from the hip, the German infantrymen tried to stop the Russians who closed in from three sides. The German squad was pushed back to the second house, and the Russians immediately occupied the first one, set up two machineguns, and opened fire on M Company men, who were coming up on the double.

The Russians threw hand grenades and explosives through a window into the second house in order to wipe out the German squad occupying this house. At first this attempt was unsuccessful, but when the house caught fire that German squad was forced to evacuate. It got outside through a damaged wall on the far side of the house. By this time the commander of Company M had taken charge of the situation and had launched a counterthrust with company headquarters personnel, reserve squads, and the squad that had initially occupied the first house. Throwing hand grenades and firing their weapons on the run, the counterattacking Germans drove the Russians from Khristishche within a few minutes. Eight Russian enlisted men and one commissar manned two machineguns in the first house, where they resisted to the last man.

GERMAN SUPPLY COLUMN returning from the front, January 1942

Upon noticing the signal equipment that the Russians had left behind in the first house, the German company commander correctly concluded that a Russian main force was assembled outside the village, waiting for the signal to advance. He called for artillery support against the suspected Russian jumpoff positions. The artillery fire began a minute later and probably prevented the Russian company from following up the attack. The remainder of the night passed quietly.

On the morning of 26 January the sun shone brightly, and the east wind continued to blow across Khristishche. Quiet reigned until 1000, when the Russian artillery started to shell the northeastern part of the town. Harassing fire continued until 1500.

At 1100, as the battalion commander was making his rounds of the German positions, a sentry from Company C reported that he had observed some suspicious movements on the forward slope of the hill east of Khristishche. A few Russian corpses which had been lying there had already vanished that morning, and he believed that the small piles of snow some 200 yards east of his post had increased in size.

The battalion commander observed the forward slope of the hill with binoculars for 1 hour, although a cold wind was blowing. He discovered a number of Russians hiding in the deep snow and cautiously piling up snow in front of them to increase their cover. The German sentries fired their carbines at every suspicious-looking pile of snow; no further movements were observed.

Russian prisoners subsequently stated that 1 Russian platoon of 40 men had been ordered to approach the town under cover of darkness and to dig into the snow. After daybreak this platoon was to push further toward the town in order to launch a surprise attack against it at nightfall. The platoon maintained wire communication with the rear.

Despite the bitter cold, the Russians remained in the snow for about 10 hours without being able to raise their heads or shift their bodies. Yet not one of them suffered frostbite.

On the basis of previous experience, the Russian commander ordered a mass attack without artillery support for that night (26-27 January). The fact that there were snow flurries and a strong east wind, may have induced him to make this decision.

The Russians assembled 3 battalions, totaling 1,500 men, for the attack. Two battalions were echeloned in the first assault wave, while the third battalion followed about 350 yards behind. The Russian regimental command post remained at the edge of the forest. Each company had 20 submachineguns, 35 automatic rifles, 10 rifles with telescopic sights, 8 heavy machineguns (drum fed), 5 light mortars, 12 pistols, and 2 signal pistols, as well as a number of rifles with fixed bayonets. Each man was issued three hand grenades and an ample supply of ammunition. All men wore padded winter clothing and felt boots.

At 0330 the Russian regiment started its attack. Any noise that the approaching Russians might have made was drowned out by the howling wind. The battalions advanced in close formation without leaving any intervals between units. The companies marched abreast in columns of three's and four's, with an interval of 5 to 10 paces between them. Without commands the Russians marched in close order to within 50 yards of the German positions and then began their assault amid wild shouting.

Only a few Russians broke into the German position; they were greeted with such a devastating hail of fire from the alert defenders that the dense Russian columns were mowed down, row after row. Nevertheless, those who survived attacked again and again.

Then the German artillery fire hit the Russian reserve battalion, which was completely dispersed. After half an hour the impetus of the attack had spent itself. Within two or three yards of the German positions the enemy dead or wounded had piled up to a height of several feet. The Russians suffered about 900 casualties in the engagement.

Khristishche remained in German hands because the garrison was alert and had learned to take proper care of its weapons.

VI. Company G Struggles Against Overwhelming Odds (March 1942)

The following action shows a Russian regiment attacking eastward in an attempt to cut off some German units and link up with friendly forces moving in from the opposite direction. The attack methods employed by the Russian infantry showed that the troops were inadequately trained. The infantry units emerged from their jumpoff position in a disorderly manner, having the appearance of a disorganized herd that suddenly emerged from a forest. As soon as the Germans opened fire, panic developed in the ranks of the attack force. The infantrymen had to be driven forward by three or four officers with drawn pistols. In many instances any attempt to retreat or even to glance backward was punished with immediate execution. There was virtually no mutual fire support or coordinated fire.

Map 6. DEFENSE OF VILLAGE T NORTH OF OLENINO

Typical of Russian infantry tactics was the tenacity with which the attack was repeated over and over again. The Russians never abandoned ground which they had gained in an attack. Frequently, isolated Russian soldiers would feign death, only to surprise approaching Germans by suddenly coming to life and firing at them from close range.

In February 1942 the 2d Battalion of the 464th German Infantry Regiment occupied snow positions without bunkers or dugouts along the western edge of Village T, situated north of Olenino near the rail line leading from Rzhev to Velikiye Luki (map 6). German reconnaissance patrols probing through the forest west of that village had been unable to establish contact with the Russians. Toward the end of February a reconnaissance patrol ascertained the presence of Russian forces in the forest. Subsequent information obtained from local inhabitants indicated that the Russians were being reinforced for an attack.

From 27 February to 2 March, detachments, consisting of about 80 Russians each, attacked daily in the same sector and at the same time. The attacks took place about 1 hour after sunrise and were directed against a point at the northwest edge of Village T. Every one of them was unsuccessful, the attacking Russians being wiped out before they could reach the German position.

On the evening of 2 March a Russian deserter reported that his infantry regiment, supported by six tanks, would attack Company G's sector, which was south of the village. To strengthen the defense of his sector the company commander, Lieutenant Viehmann, placed three 37-mm. antitank guns behind the MLR and planted antitank mines across the road leading southwestward. Although his unit was under-strength, Viehmann ordered each platoon to form a reserve detachment of 10 men for a possible counterthrust.

At daybreak on 3 March two Russian heavy tanks of the KV type, painted white to blend with the landscape, were spotted standing at the edge of the forest about 500 yards in front of Company G's sector. At 0820 Russian aircraft bombed the village, while the two tanks, about 150 yards apart, advanced another 100 yards, stopped, and opened fire at the most conspicuous German fortifications. At 0830 four more Russian tanks, this time T34's, emerged from the forest. They paired off, penetrated the right and center of Company G's MLR, and rolled up the stretch between the two points of penetration. Encountering no effective resistance, they pushed deeper into the German defensive position while providing mutual fire support. The three German 37-mm. antitank guns proved ineffective against the T34's and were quickly knocked out, as were a number of German heavy weapons. However, without immediate infantry support the Russian tanks were incapable of achieving any further results.

GERMAN FOXHOLE near Rzhev, February 1942

It was not until 2 hours later that approximately 300 Russian riflemen attacked from the forest, while the two KV tanks stood still and the T34's roamed at will through the depth of the German defensive position. Hampered by the deep snow, the infantry had to bunch up and advance along the tank tracks, offering easy targets during their slow movement. Despite the loss of many of their heavy weapons, the German defenders mustered sufficient strength to repel the Russian attack and to force the infantry to withdraw into the forest, the tanks following soon afterward.

A short time later the four T34's reappeared. This time each tank carried a rifle squad. Additional infantry supported the attack. When the T34's re-entered the German MLR three of them were eliminated by German infantrymen who threw antitank mines into their paths. The Russian foot infantry elements advanced 350 yards from the forest's edge before being pinned down by German mortar fire. The one tank that remained intact quickly withdrew into the forest, followed by the Russian infantry. Throughout the day the two KV's remained in the German outpost area and fired on everything that moved within the German position.

Russian prisoners taken during the fighting stated that the riflemen mounted on tanks had been ordered to establish themselves within the German defensive position to support the Russian infantry's attack. These statements were confirmed when it was discovered that a number of small Russian detachments had infiltrated the German outpost area, from where they refused to be dislodged despite the severe cold. After dark, German combat patrols were finally able to move out and liquidate them.

All was quiet on 4 March. The next day the Russians resumed the attack all along the 2d Battalion sector with a force estimated at 2 to 3 infantry regiments and supported by 16 tanks. While the Russian artillery confined itself to harassing the German rear area, the mortars laid down intensive fire, whose effect was insignificant because of the deep snow. Severe fighting continued unabated until evening. After dark the Russians broke into the southern part of Village T at several points. By that time severe losses in men and materiel had greatly weakened the defending force. Nevertheless, the Germans held the northern part of Village T until the morning of 6 March, when they withdrew to a new position 2 miles farther east.

In this engagement the Russians demonstrated extraordinary skill in approaching through the snow-covered forests without attracting the attention of the Germans. They permitted small German reconnaissance patrols to pass at will to create the impression that the forest was clear.

The four limited attacks that preceded the main assault were either feints or reconnaissance thrusts in force. By repeating them against the same sector on 4 subsequent days, the Russians probably intended to divert German defense forces to that point.

During the main assault the teamwork between Russian tanks and infantry was inadequate. In this particular engagement the Russian infantry showed little aggressiveness, and the tanks had to advance alone to break up the German defense system before the infantry jumped off. Actually, the long interval between tank and infantry attacks had precisely the opposite effect. It is true that the Russian tank attack threw the German defense into temporary confusion, because the 37-mm. antitank guns were ineffective against the T34rs and KV's and the German infantry lacked experience in combatting tanks at close range. Moreover, the two KV tanks acted as armored assault guns and prevented all movements within the German position. These often-used tactics were successful as long as the Germans did not have antitank guns whose projectiles could pierce the armor of these tanks. However, by the time the Russian infantry launched its attack two hours later, the defenders were able to overcome their initial fear of the giant KV tanks and to rally sufficient strength to frustrate the Russian infantry attack. When the Russian armor attacked for the second time, the German infantry knew how to cope with it effectively.

As in many other instances, the lower echelon Russian commanders revealed a certain lack of initiative in the execution of orders. Individual units were simply given a mission or a time schedule to which they adhered rigidly. This operating procedure had its obvious weaknesses. While the Russian soldier had the innate faculty of adapting himself easily to technological innovations and overcoming mechanical difficulties, the lower echelon commanders seemed incapable of coping with sudden changes in the situation and acting on their own initiative. Fear of punishment in the event of failure may have motivated their reluctance to make independent decisions.

The Russian troops employed in this action seemed to be particularly immune to extreme cold. Individual snipers hid in the deep snow throughout day or night, even at temperatures as low as — 50°F. In temperatures of —40° F. and below, the German machineguns often failed to function, and below — 60° F. some of the rifles failed to fire. In these temperatures the oil or grease congealed, jamming the bolt mechanism. Locally procured sunflower oil was used as a lubricant when available, as it guaranteed the proper functioning of weapons in subzero temperatures.

VII. Company G Annihilates a Russian Elite Unit (March 1942)

During March 1942 Russian pressure from the north and west forced the Germans to make a limited withdrawal northwest of Rzhev. In late March the 2d Battalion of the German 464th Infantry Regiment, including Company G, established defensive positions in Village S, about 12 miles northwest of Olenino. The village was situated on level ground and was faced by forests to the north, east, and south (map 7). The terrain to the west was open, permitting the defenders to detect at an early moment the approach of any Russian forces coming from that direction. Since the German forces in the area were not strong enough to establish a continuous defense line, the village was organized for perimeter defense. The battalion constructed snow positions above the ground, excavation of the frozen soil being impossible, and maintained contact with adjacent units by sending patrols through the forests around the village. On 25 March the low temperature was —44° F. and 3 feet of snow covered the ground. On that day the 2d Battalion repelled several attacks from the west, inflicting heavy losses on the Russians, who then intensified their patrol activity.

Map 7. DEFENSE OF VILLAGE S NORTHWEST OF OLENINO (25-26 March 1942)

Before dawn on 26 March a reconnaissance patrol sent out by Company G returned from the forest bordering Village S to the north without having encountered enemy troops. The distance from the edge of the forest to the defense perimeter measured approximately 150 yards. Half an hour after the return of the German patrol 100 Russians suddenly emerged from the forest and attacked Company G at the northwestern part of the defense ring. The Russians participating in the attack were armed with submachineguns and moved on skis, which made the small force exceedingly mobile in the snow-covered terrain. In addition, every third man carried a frangible grenade in his pocket, presumably for the purpose of setting fire to the village. Several Russians literally blew up when their frangible grenades were struck by bullets and exploded. Because of the severe cold some of the German machineguns failed to function, and the Russians succeeded in penetrating the German positions.