Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

PRINCIPLES AND EXPERIENCES OF POSITION WARFARE AND RETROGRADE MOVEMENTS

BY GENERAL DER ARTILLERIE WALTER HARTMANN

Part I: Descussion of the principles of position warfare, and account of the experiences of a division in such a situation.

Part II: Discussion of the principles of retrograde movements, and account of the experiences of a division which retreated 60 kilometers by stages.

Part I

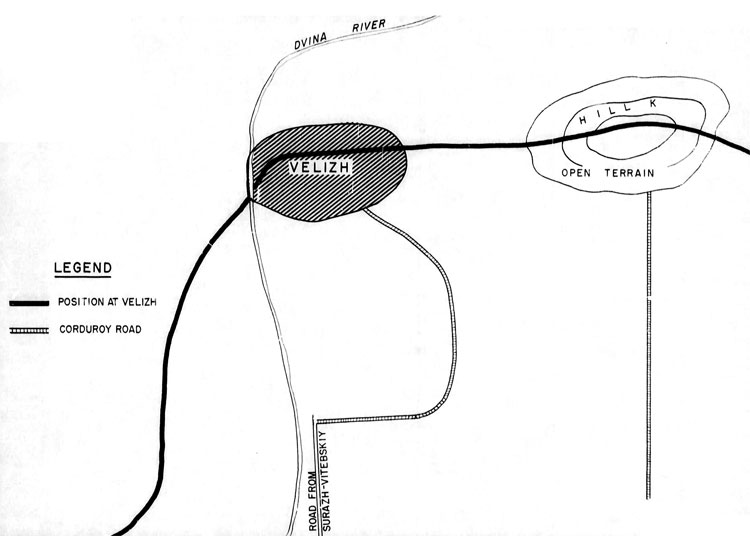

A. Situation (sketch 1)

The division is in position in its sector near VELIZH on the upper DVINA, supported on both flanks. The DVINA crosses the front at a right angle. VELIZH is within the own front lines. The division is reinforced by one light infantry brigade and two additional battalions. The width of the sector front is approximately $0 kilometers.

SKETCH 1. POSITION AT VELIZH

B. Topography

The sector is gently rolling country which does not permit extensive observation of the depth of the enemy territory. The terrain is wooded and contains large swamps which are, outside of the roads, often impassable on foot, but in any event impenetrable for vehicles. This swamp area is interspersed with islands of firm ground, either with or without forest. The two opposing positions are built on these firm islands. Twenty kilometers of corduroy road had been laid to provide access to the several regimental sectors. The town of VELIZH and its vicinity, as well as a large, flat, elevated plateau about fifteen kilometers to the right (called Hill К in sketch 1) were open terrain without swamps. The Russian positions at the ridge near К dominated the German positions and rear areas by virtue of superior visibility. Near VELIZH the advantage was on the side of the German positions.

Experiences; Although we considered the swampy terrain generally as impassable, it is not to be looked upon as absolutely safe protection against enemy surprise actions. The Russians know the country and have been accustomed to it for generations. They always know how to find islands and paths, as well as other ways for launching offensive activities.

The following principle should therefore prevail: There is no impassable terrain.

C. Position Warfare

1. Strength of trench complements:

The strength depends upon the importance of each particular sector. As can be seen from paragraph В [above], the roads leading to an important communication center made VELIZH and Hill К decisive points. The enemy's desire to break through at these points made them the focus of constant local engagements. For that reason the strength of trench complements (including regimental reserves) was about 25 men 2 per 100 meters, the highest number which I have ever experienced in position warfare. On the other hand, the strength in the less frequently attacked positions was correspondingly lower - in the actual swamp positions about 15 to 20 men per kilometer.

Experiences:

It is important to give constant attention to the strength of the trench complements, and to make appropriate adjustments in accordance with the changing situation. The maintenance of a graphic chart provides an instant picture of the changing strength. The entire front sector is to be divided into sub-sectors one kilometer long, and the corresponding strength of complements to be entered as follows:

| Date | VELIZH |

HILL K |

1 km |

| May 1 | 20 | 24 | 28 | 13 | 18 | 26 | 30 | 32 | 27 | 16 |

| May 30 | 32 | 38 | 36 | 18 | 18 | 21 | 19 | 21 | 27 | 19 |

Similarly, a graphic chart of losses is recommended. On such a chart, divided by front-kilometers, the daily losses are shown in the sector in which they occur. (The basic pattern is the same as that of the strength chart.) Very soon it became evident that rather heavy losses were sustained again and again at certain points, or that such casualties occurred at different points at different times. It follows that positions had to be improved, especially at points at which casualties recurred frequently, in order to reduce casualties. Whenever casualties occur in a sector heretofore spared, it can be deduced that the enemy has increased his activity at this locality. To lower casualties constantly in daily position warfare is an especially important task of the division - a part of its command function. A graphic chart as described above is a good aid in this task. At the same time it provides a good and instantly available picture of the enemy activity during a given period. A similar record of both own and enemy combat patrol activities reveals instantly, in form of a chart, a clear picture of the own and enemy situation.

2a. General remarks about the position in the division sector.

The particularly noteworthy fact about the divisions employed in position warfare was that the frontages they had to defend were substantially larger than their effective strength warranted. As a result, the organization of reserves remained a difficult problem throughout. Also, since these reserves ware very weak, the trench complements could only be relieved very seldom, if at all. Here, without fanfare, the troops in the trenches performed heroically, in a manner believed impossible by pre-war military thinking. The intermediate command (division) had, therefore, to devote even greater effort to finding ways and means for mitigating these disadvantages and preserving the physical and mental stamina of the front soldier even during prolonged periods of duty in the trenches. Only minor measures were taken, but they grew in importance because of the trying conditions mentioned above. These measures, generally speaking, consisted of an improvement of the position. I do not refer to improvements of positions brought about by own attack, these required the assignment of combat units from higher headquarters. The division could, therefore, achieve an improvement of positions only by relinquishing especially unfavorable points. This pays off every time and enables the troops better to defend the positions. It means strength, not weakness, of leadership.

Examples: The forward line of the position near VELIZH was drawn in front of the town, the inclusion of the town itself into the defense position was an advantage. Even a totally destroyed and demolished town offers a succession of possibilities for defense against local penetration. Thus, attacks of the enemy, ranging in strength from battalion to division, collapsed in the town. An attack against a town can succeed only if medium artillery is available in adequate numbers, i.e., after preparations which an alert enemy with sufficient air reconnaissance cannot overlook. The Russian attacks lacked sufficient support by medium artillery.

It is unfavorable to place the defense line inside the town. Such a line requires and wastes too many forces. Had the enemy succeeded in forcing his way into parts of the town, the correct and appropriate measure would have been a withdrawal to a line behind the town. However, the division was not faced with this problem. The withdrawal of a forward line is advisable when the observation of enemy territory is thereby improved, and enemy observation of the own rear area obstructed. Such a gain, however, is illusory if withdrawal means a substantial extension of the front. This was the case at Hill K. For this reason the defense line could not be abandoned at that point, and the disadvantages described in paragraph В above had to be endured.

Positions on a reverse slope with outguards on the crest are no longer appropriate in this age of tank and air warfare. This type of position is to be considered only when backed up by a higher elevation which sufficiently assures artillery observation. Positions with a rather extended frontage, meeting the above-described requirements, are rare in the Eastern Theater of War. Such positions, if found in a defense sector, may be selected whenever they can be incorporated in the front line without increasing its length. They offer the advantage of giving freedom of movement to the troops during the day by obstructing the enemy's visibility. The attendant disadvantage is the additional drain on the available manpower for the occupation of outposts on the crest of the elevation. An active enemy will also seek to reach the crest, and local fighting for its possession may make such a position a constant trouble spot.

2b. Construction of positions.

The sector which, as a matter of fact, was much too large for the division, accentuated the problem of economy of manpower. It was mainly a problem of the infantry. Without relief the infantry had to fight, build fortifications, rest, and, as far as possible, conduct training. The fighting power of the trench complements could only be maintained by careful planning and avoidance of overexertion. It was an ever-recurrent experience that a tremendous amount of digging was wasted whenever no plan existed for the construction of positions. Such a plan must be prepared for each company, with due regard for situation and terrain.. The thought of providing first of all protection against enemy fire, then rest, and finally freedom of movement to the rear, leads to the following natural sequence: 1. Improvement of the forward trench and construction of shelters against light and medium mortars; 2. Construction of 3hellproof dugouts; 3. Building of communication trenches to the rear (one per battalion).

Whether point 2 or 3 should be given preference depends in every саsе on local conditions. Tackled next, after the above-mentioned most essential measures had been taken, were improvements and perfections in the depth of the defensive positions (machine-gun emplacements and switch positions), facing local penetrations. In the preparation of

the plan for the fortifications one had to keep in mind that construction material had to be brought up, and that building was possible only at night. The plan was drawn at battalion level with the aid and under the supervision of construction specialists. Thus, haphazard building by individual companies, often without co-ordination with the adjoining companies, was avoided. Piecemeal building of field fortifications would have meant a maze of short trenches, which make a coordinated defense difficult and complicate operations in case of smaller penetrations by the enemy.

2c. Forest positions.

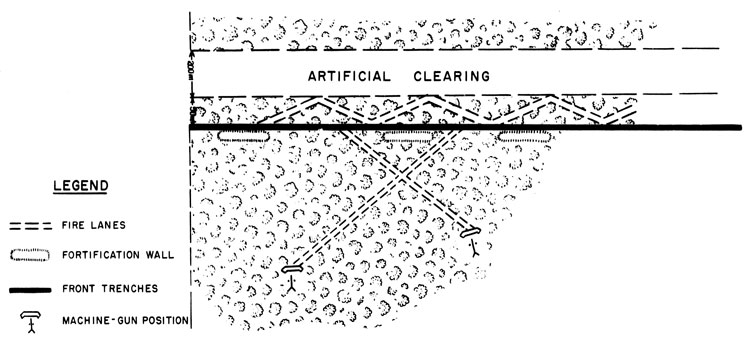

Large segments of the division sector were purely forest positions, A series of local forest skirmishes and the successful defense against local attacks and attempted breakthroughs has proved the following layout to be the most efficient for forest positions:

The front line is not placed at the edge of the forest, but rather 50 to 100 meters inside it. If the forest is dense, the line is pushed closer (about 50 meters, to the edge; if it is thin, it is placed, farther back. If the position does not run along the edge, but rather through a large forest, a clearing 100 to 200 meters deep, has to be cut about 50 meters in front of the position, provided the distance to the enemy line is sufficient (e.g., 1 kilometer) to permit it. It is important that a zone, even if limited in size, be created in front of the own position, permitting free and unobstructed visibility. The removal of underbrush in front of the position is part of the preparation. Where the woods were thick, protective lanes of fire, extending to the main clearing, were cut for machine guns. Wherever the enemy was close (200 to 500 meters), it was worth-while to erect a parados immediately behind the own trenches, so as to be able to move mогe easily and safely even during the daytime. Lanes of fire were cut in order to clear a field for effective fire from machine guns located in emplacements deep inside the defense position. Part of the trench was covered as shelter against tree bursts.

SKETCH 2. DIAGRAM OF FOREST POSITION

3. Operations

a. Reconnaissance and combat patrols.

As has been mentioned before, no attacks in battalion or greater strength were planned by us to improve our position or for any other purpose. It remained the primary task of the division to hold the position, including the key points VELIZH and Hill K, against all enemy attacks. In order to succeed in this task it was necessary to conduct an especially active defense on a lower level, since we had to forego larger attacks. This was the decisive factor in saving us from getting into a rut and losing confidence in our own superiority.

The means used was reconnaissance, which formed a basis for active combat as well as an important part of actual combat. The results of all visual day observations, night patrols, and air reconnaissance, were translated into infantry and artillery actions which were planned from battalion level up to division. These actions consisted of the use of snipers, combat patrols, and artillery fire against identified command posts and batteries. The available supply of ammunition, always limited in the defensive, made it necessary to designate definite authorities competent to decide on the expenditure of ammunition at battalion, regiment, and division level. Furthermore, orders had to be given аs to the time at which identified targets were to be fired on. This depended, among other things, on the enemy's daily routine. Trench listening devices may be used to good advantage as a supplement to reconnaissance wherever the own and enemy positions are close (100 to 200 meters. In this manner the division learned of intended tunneling operations near VELIZH, and could take suitable countermeasures in time. The enemy, however, gradually improved considerably his security discipline with reference to talking in the trenches, and thus took the ground from under this means of gaining information. This type of small-scale operation can succeed only if all reconnaissance and intelligence activities are well organized and quickly translated into combat actions without a fixed pattern. Other small-scale operation were the nightly combat patrols. They served the purpose of reconnaissance, and could be considered offensive operations on a small scale. They maintained, and considerably increased the morale of the troops and their confidence in their own superiority. Only surprise could assure the success of these patrols. The objective - a certain part of the enemy trenches or an advance position - was carefully selected in advance. Before the actual undertaking, reconnaissance patrols ascertained at night whether the enemy still occupied those particular trenches. Similarly, it could be learned whether the enemy was particularly alert in that position, and, as a result, whether surprise could be achieved. It was to be determined whether the operation should take place during a moonlit or a dark night. Next., the attack was practiced behind our own lines at a location offering conditions similar to those of the real objective. The operation itself was assigned to the personnel which had conducted the reconnaissance, and which was thus familiar with the real objective. A further decision had to be made whether the operation was to be supported by artillery. Experience has shown that artillery support frequently alerts the enemy, and thus jeopardizes the element of surprise. It was, however, advisable to assign to the attacking force an artilleryman with a radio set, especially where the objective was rather distant from the own lines. After the completion of the mission, artillery fire was to be called for as a kind of barrage to cover the return to the own lines. All in all, preparations were made down to the most minute detail - the same as for a night attack on a larger scale. During all these cumbersome preparations, however, none of the participants doubted the final success. The battalion commander was in charge of these preparations. The number of combat patrols had to be limited so as not to overtax the troops and thus endanger the defense. Considering the over-all situation, even one raid of combat patrols per battalion per month meant a great deal. It is absurd to issue orders at higher headquarters that a raid is to be executed within the next three days. This may be justifiable in the very first stages of position warfare. At a later stage it leads to certain failure. In addition to rather large attacks by the Russian enemy, he was also very active in night reconnaissance and combat patrols. Because of their primitive way of life, the Russians were better adapted to night activity, that is, night fighting. In other words, they have the characteristics of an animal prowling by night. This had to be counterbalanced by our own actions. Because the complements holding the trenches were so weak, the troops had to rest by day, whereas trench complements were maintained at maximum strength by night. This rule was relaxed only during moonlit nights.

b. Reserves

Reserves discussed here are not those assigned by higher headquarters, which are necessary whenever it is recognized that major attacks by the enemy are imminent, but reserves organized out of the division's own manpower. Without them not even small-scale operations could be carried out successfully in position warfare. It was difficult to form such reserves, and to place them advantageously. Despite all misgivings, these reserves were formed by weakening still further the already weak trench complements. The withdrawal of a whole battalion from the entire sector of the division (50 kilometers) was the absolute limit considering the thinly manned lines. This meant necessarily a further lengthening of the individual sectors. However, such a reserve battalion could not be held as a unit behind the division sector. In view of the extended frontage and the small пumbег of access roads, which in part consisted only of narrow corduroy roads with occasional by-passes, such a battalion would usually have arrived too late to be of use against enemy attacks. To divide the battalion into companies, and to assign the latter to the regimental sectors, placing them under the regimental commander, was not a good solution either. The battalion as a tactical unit thus would have ceased to exist, and the battalion commander's functions would have been eliminated for all practical purposes. The solution of resting, rehabilitating, and training a battalion behind the front, and at the same time keeping it available as reserve, could therefore not be applied. As an expedient, one company, plus elements of the machine-gun company, was pulled out from each regimental sector and used as reserve. This solution shows clearly that that reserve could not even be called a tactical reserve. It was really nothing more than a pureLy local, small, combat reserve. It was, on the other hand, quickly available in case of enemy attacks and local penetration - a decisive factor in a successful defense. (See paragraph с below - Penetrations). At the same time, these reserves remained unfortunately within reach of the enemy's small arms, mortars, and artillery. The highly necessary mental ana also physical relaxation was, of course, mostly lost. The local reserves of the battalion were usually the battalion headquarters reinforced by a squad, those of the company a squad. Nevertheless, our troops, realizing the necessity, accepted all these hardships heroically.

c. Penetrations

Particularly at the front sectors of VELIZH and Hill К did the Russians develop lively offensive activity in the form of attacks by units ranging from battalions up to a division. These attacks differed from large-scale attacks on a broad front with a strategic objective in that they were carried out on a narrow front at night, or in the late afternoon about two hours before darkness. The reasons for this timing were obvious to anyone who knew the enemy and his way of fighting. He was an expert in consolidating his gains by quickly filling newly won trenches with fresh troops. He made these new positions so strong that German counter thrusts or counterattacks aiming at restoring the situation meant considerable losses if launched later, or on the following day, and were doomed to failure unless carefully prepared and supported by heavy weapons. At night the manning and consolidation of newly won territory was, of course, much easier and simpler for the enemy; that is why he timed his attack as described above. However, even by day lie was unsurpassed in this way of infiltration. These tactics were recognized, and attempts were made to counteract them with artillery, but in the end this led to a waste of ammunition without visible success. Sometimes, but not always, the imminence of enemy attacks was recognized in advance from the preparations. Intercepted messages, the arrival of reinforcements, and the increase of trench complements were indications of an imminent attack. Statements of prisoners largely lacked credibility and reliability. At the same time, the apparent reinforcements might also be nothing more than replacements. Nevertheless, the suspicion that an attack might be imminent had to produce immediate counter measures». The enemy attack was launched either with or without artillery support, depending on whether the enemy's jump-off position was far from, or close to our trenches. Near VELIZH, for example, the trenches were only 50 to 100 meters apart at some points. Here the attack was naturally launched without artillery support, as a surprise assault from the jump-off position. wherever the enemy advanced under the protection of his own artillery, he showed his superb training by hugging the fire curtain almost to the point of self-sacrifice. In other words, if an imminent attack could not be broken up in time by artillery fire, it was usually impossible to avoid temporary penetrations.

Defense:

Whenever an attack was recognized in time, an attempt was made at breaking it up with all heavy weapons from mortar up to medium artillery. It was purely a matter of properly functioning artillery. Target area and time were exactly prearranged. By simple symbols, the target areas were marked on the map in advance, for instance, fire on target area L and M from 2000 to 2010. Orders had been given for every heavy weapon as to the target area and its specific target within the area. If this artillery defense functioned properly, it was an important factor in a successful defense - not always completely checking a penetration, but at least preventing its extension by the enemy. Defensive fire which lasted too long not only meant an excessive expenditure of ammunition which the defense could not afford, but it was also less effective than a frequent repetition of this defensive fire at irregular intervals.

I now come to the discussion of the infantry defense. Let us assume that the initial penetration of the enemy had succeeded, as was often the case. It was then essential to take full advantage of his temporary weakness. This weakness was the result of two factors: First, the enemy who had penetrated into our fortifications did not yet know his way around, and therefore felt not sure of himself; second, the enemy artillery fire was at this stage not trained on the contested trenches. With lightning speed one had to take advantage of this situation. The company and battalion reserves had to act on their own initiative during the counter thrust, and, without awaiting orders, clear the trenches of the enemy who had penetrated. Spirited troops under the resolute leadership of officers or noncommissioned officers were usually successful in this respect. The regiment had to bring up its combat reserve immediately (see paragraph "reserves") as replacements for casualties and as reinforcements against possible further attacks. If the enemy, who had penetrated, could not be thrown back within a short time (two or three hours), further attempts along this line were useless in view of the limited forces available. In this case it was vital to seal off the penetration on both sides by means of the regimental reserve. It was imperative to avoid an extension of the penetration. Only counterattack could now restore the old situation. Whether it was ordered by the division depended on the importance of the lost trenches. Such a counterattack was always difficult because of the small forces available, and a gamble. The necessary troops had to be taken from another sector, and had to become familiar with the terrain. All this required time, and could not be rushed. The most important factor, however, was that even a successful attack resulted in heavy casualties, caused by enemy artillery fire after the attack. This happened because the trenches, after recapture, were usually so badly battered that they offered only scanty cover for the time being. №e decision whether a lost fortification should be regained was, therefore, a serious one for the command.

I have already emphasized in the chapter on construction of positions, that a well laid-out trench system was important for successful waging of position warfare. The description of trench warfare in this chapter undoubtedly shows the need for such a trench system. The VELIZH sector consisted of a maze of trenches, a relic from earlier battles. Many of these trenches were filled in, or else made unusable with the aid of barbed wire. Even attacks by a whole enemy division were not carried beyond the front trenches. The artillery was not yet overwhelmingly strong, and ammunition, especially for medium artillery, was not used as lavishly as later on. Thus our artillery could successfully cope with the tremendous numbers of attacking infantry and make the defense fully successful. This strengthened our feeling of superiority.

d. Use of heavy weapons.

This paragraph is a discussion of the employment of machine guns and antitank guns. Again and again the question came up whether to employ these weapons only in the forward line, only in depth of the position, or partly up front and partly in the depth of the position. It is undoubtedly clear that no unequivocal answer is possible. It depends rather on the over-oil situation, that is, the prevailing circumstances. Let me clarify: If it is said or ordered that every attack must be crushed in front of the defender's forward lines, the whole defense plan must be designed to make the heavy weapons effective particularly in front of the own trenches. Accordingly, they have to be placed in an advanced position. If, however, in a changed situation the enemy blankets and destroys the front trenches completely with artillery fire before ana during the initial stages of the attack, heavy weapons employed in advanced positions can no longer be effective. If the relative strength has developed to a point where penetration of the front trenches cannot be avoided during larger attacks, the heavy weapons should not be placed forward.

The defensive mission of the heavy weapons units has to be changed along with the changing situation so as to make it their task to limit an enemy penetration and to prevent its becoming a breakthrough. For that purpose heavy weapons have to be placed inside the main battle position at a distance of one to four kilometers behind the front trenches, depending upon the terrain, decisive points, and the number of heavy weapons.

e. Communications

The basic concepts of coordination of telephone, radio, and light signals were applied. Double telephone lines were an additional safeguard.

f. Conclusions

In reading the chapter on operations, it might be concluded theoretically that an attack cannot succeed unless made with tremendously superior forces. Consider, however, how much misunderstanding and friction occurs even in normal, everyday life. This is multiplied in combat with all its death-dealing weapons. For example, four batteries are committed in the defense of an attacked sector, but perhaps only one of them fires on the proper target area, the second is neutralized by counter battery fire, and the remaining two batteries aid not receive their orders because of destroyed communications.

The smaller the breadth of the enemy attack, the more effective can units not attacked, especially artillery, take part in the defense of the threatened position. Considering the small defense

forces, the experience gained may thus be summed up as follows: "The success of the defense becomes more uncertain as the width of the attack increases." Apart from the skill and heroism of the troops, the secret of our continuous success in defense was the fact that there was no

surprise with regard to the area to be attacked, and that breadth of the attacks aid not exceed 1200 meters.

All through Part I emphasis has not been placed on basic concepts of tactics on a large scale, but on all the little tactical expedients and improvisations. Nothing can serve better to illustrate at a low level the reasons for losing the war than a description of the ways and means forced upon us for command and conduct of combat. This dire situation of command and troops grew worse and worse, finally the breaking point was reached.

Part II

A. Initial Situation

The Russian large-scale attacks had begun to push back the German front in an area far to the south of our division sector. During the fall these attacks shifted to areas closer to the division. Higher headquarters decided on a strategic withdrawal of the division, as well as the adjacent units on either side, before the start of a large-scale attack against our positions. The decision was made, among other things, in order to maintain contact with the southern fronts, which had already been moved back. The actual order was received by the division two days before the first withdrawal. The general outline of the mission, as given in the orders, was approximately as follows: The division will withdraw step by step into the new position P-R. (This position was located about 50 kilometers behind the previous one.; The position is at this time being prepared for defense. Such intermediate position to which the division will fall back according to orders will be held until the receipt of orders for further withdrawal to the next position. The timing of the step-by-step withdrawal to the final position P-R depends on the overall situation. It is imperative to hold every intermediate position against enemy attacks until a new withdrawal is ordered.

The entire withdrawal, including the fighting in the intermediate positions, lasted five weeks. The division reached position P-R at the beginning of the sixth week, during the last days of October. Once the enemy began to attack, it ceased to be a step-by- step withdrawal according to plan. The mission was made extremely- difficult by a restriction to the effect that the individual intermediate positions were to be evacuated only on orders from higher headquarters, and not when the situation on the own front sector made retreat advisable, only a division which had proved its worth in previous battles could succeed in carrying out these orders. The command was constantly plagued by the worry about how long the division would be able to hold out, and whether the withdrawal would then will succeed; but our division was successful. No reinforcements of infantry or artillery were assigned to the division for the completion of the mission. On the other hand, the urgent need for assignment of tanks or assault guns became evident upon the withdrawal to the first intermediate position. Accordingly, the division was reinforced by a panzer battalion, the strength of which varied between eight and thirteen tanks. The sector frontage was also reduced during the withdrawal into the first position; after all, the entire retrograde movement also gave us the decisive advantage of a shortened front.

D. Preparations for the retrograde movement.

Having spent a number of months in position warfare, the division could not suddenly change over to mobile warfare without some difficulties. Our mobility had been considerably limited due to the loss of horses which had not been replaced, and the transfer of motor vehicles to other units. Only 48 hours were allowed until the start of the first retrograde movement. On the other hand, it goes without saying that no material was to be left behind. All this vas accomplished only because two motorized columns were made available. An additional difficulty was presented by the limited number of access roads, consisting almost exclusively of one-way corduroy roads with occasional by-passes. It was essential that the enemy air reconnaissance be prevented from recognizing the planned retrograde movement. In formulating the orders which had to be issued immediately, the following points had to be considered:

1. What can and must be moved to the rear during these two days, and

2. When?

Advantageous was the fact that combat, trains and supply services had been located behind the first intermediate position because of the swampy terrain. The following were immediately moved to the rear:

1. Ammunition dumps, less three days' ammunition supply;

2. Part of the artillery, and some of the antitank guns.

Traffic control was improved. In daytime, six hours were reserved for frontward, and three hours for rearward traffic, whereas when during the night, when enemy air reconnaissance was limited, the procedure was reversed. Thus, the retrograde movement was to be concealed from the enemy. Furthermore, the movement of motorized and horse-drawn vehicles had to be regulated.

Reconnaissance and survey of own future positions.

The first intermediate position to be occupied in the retrograde movement was located about nine to eleven kilometers behind the defense position at VELIZH. The left wing of the division (one regiment) was not affected by the withdrawal, because its position was no longer on a level with the other parts of the division but bent toward the rear (see sketch 1, part 1). Apart from the trenches and strong points in the battle position (up to live kilometers behind the front trenches), there were neither improved positions nor any\ kind of strong points farther to the rear. The following lesson, taught by experience, is to be emphasized in this connection. Reserve positions often did not serve their purpose. Large-scale breakthroughs rolled over these positions which could not be manned in time with fresh forces. Enemy penetrations did not stop at reserve positions but at points where fresh forces could be thrown against the declining momentum of the attack. The construction of reserve positions serves its full purpose only if it is planned to withdraw to that position in time - that is, while there still is full freedom of action. It must be intended to give way to overwhelming enemy pressure if and when a certain situation arises. Even the best position is of no value unless occupied in time,and this is possible only where there is freedom of action. Where should one suddenly and quickly find forces for the manning of a rear position when the waves of a large-scale attack are surging through a broken front? Had this manpower been available, it would naturally have been set aside as a reserve already before the start of the large- scale attack. The division could depend on construction work being done on the final position F-R during the withdrawal movement. Whether the improvements would be fully completed at the time of the division's arrival could naturally not be foreseen.

No improvements had been made on the first intermediate position. However, the position as a potential line of defense had been surveyed previously, staked out, and divided into sectors. The various battalions had received sector assignments, and had familiarized themselves with them. The artillery positions and observation posts had been surveyed in the same manner, ana the entire artiLlery organization had been mapped out. These advance measures facilitated a systematic and effectual occupation of the new position at a time when the division had to change from position to mobile warfare. The only small changes that had to be made in the advance plans had become necessary because exact sector limits had not been set previously.

I shall call the first position to which we were to withdraw "Position One," and the day of withdrawal "X-day." From one to two kilometers in front of Position One, depending on the terrain, a covering position was planned. It did not consist of an unbroken line, but rather of individual strong points. Their purpose was to cover the occupation of Position One, and to screen it against enemy reconnaissance. Thus it was intended to delay the enemy's preparations for an attack against Position One. For the retrograde movement the covering position was, at first, a rear-guard position and became, after occupation of Position One, an advanced position.

Elements of the artillery, which were to be moved back before x-day, were placed in positions between the rear-guard position and Position One on x minus 1. The medium artillery, with its longer range, could fire on enemy targets even from there. One piece from each of the batteries that had been withdrawn remained, nevertheless, in the old position in order to maintain, or rather feint, the normal artillery fire of the previous days to a certain degree. The infantry that was intended for occupation of the rear-guard position was withdrawn in the same manner, and placed there on x minus 1. This made it possible for them to establish themselves at least somewhat in the new defense position up to the evening of x-day. The defense did not consist of an unbroken line; only a few decisive points were occupied. They were selected chiefly with a view toward the blocking of roads and paths because all mobile warfare - and, from the er.emy point of view, this seemed imminent - normally develops at first along roads. The timely construction of the communications net in Position One was another vital preparatory measure, which enabled the division commander to learn in time where the pressure of the pursuing enemy became particularly strong. Nothing but a constant flow of information on the enemy enabled us to bring up the limited reserves in support of the small defending forces at the threatened point. The exact location of the regimental and battalion command posts was, therefore, designated in

advance in order to assure the quick construction of communications. Without interrupting communications, locations of command posts could be changed, if necessary, after arrival of the headquarters at Position One. This procedure has not only proved itself adequate but, in fact, the only way to guarantee continuity of command. Radio traffic, which had been allowed in the defense only in case of enemy attacks, was permitted after the occupation of Position One.

C. Withdrawal to Position One.

For a successful withdrawal it was essential that the enemy should not recognize the intention in advance and interfere with the withdrawal movement. The measures contemplated for the time prior to x-day have been described in Part B. For x-day ana the night itself the following additional measures were essential:

1. On x-day, our front had to present an unchanged picture to the enemy. A conspicuous increase or decrease of firing activity, compared with that of previous days, had to be equally avoided. The usual patrol activities would have been desirable, but had to be omitted because the necessary forces were not available.

2. Timing: The withdrawal itself had to take place under cover of darkness. Considering the difficult road conditions and the necessity of allowing the troops the greatest possible amount of time for occupying the new position before the enemy attacked, the proper time was immediately after darkness. The danger of premature silence in the old position had to be avoided. It was therefore ordered that certain machine guns in the depth of the position, as well as certain

artillery pieces and mortars, should fire according to a specified timetable. They were placed under the command of the rear-guard units, and moved back with them. The loss of some of the heavy weapons was unavoidable. The rest of the troops who had been committed in the combat zone were marched back in small groups, and were collected by companies at prearranged points in the rear area. This was not difficult for the troops who were familiar with the terrain.

3. Rear guards. These were the troops who remained in the position, and were withdrawn shortly before dawn in accordance with a specific timetable. Of course, the front position was now no longer fully manned, but only consisted of certain strong points occupied by rear guards. The terrain between these strong points was covered by a few machine guns, mortars, and artillery pieces which had remained in their emplacements in the depth of the position. Their mission was to close and cover, to a certain degree, the gaps in the front line.

The difficulty of maintaining firm control is always the .main problem of rear-guard operations. Such a control can only succeed with the help of good communications. The front was very wide, and the few heavy weapons in the depth of the position could not remain cut off from communications. Most of the old command posts were no longer occupied, the telephone switchboards had been moved, and radio traffic was prohibited. The existing telephone lines were fully utilized for the establishment of connections between strong points and heavy weapons in the depth of the position, but they had to be supplemented and changed to match the requirements of the rear guards. The commanding officers of the various sectors had to report

to neighboring units the enemy situation in their respective sectors, direct the harassing fire during the night, and make independent decisions in the event of enemy attacks.

The time for the withdrawal of the rearguard was set for 2 1/2 hours before dawn. Provided the епеmу did not interfere, all other withdrawing elements would have reached Position One by that time. To leave the rear guard in the old position until the enemy would recognize the withdrawal - which might not have happened until daybreak - would have meant sacrificing these troops.

4. Instructions to be followed in the event of immediate pursuit by the enemy:

Should the enemy, despite all precautions, recognize the withdrawal from the position during x-night, and pursue immediately, the following instructions are to be followed: Withdrawing units which are attacked by the enemy will fight back then and there. Units that have already withdrawn farther to the rear, and reserves, will not be brought up as reinforcements. 3very momentary defensive success must be exploded by resuming the interrupted retrograde movement. The purpose of these instructions was to avoid that rather large forces be locked in battle in front of Position One or the rear-guard position. These forces would most probably have been annihilated. They would then not have been available for the manning of Position One, and their loss would have endangered its successful defense. Throughout the war, we as well as the enemy experienced time and again that at night even well-trained troops in pursuit advance only hesitantly in the absence of a predetermined plan. The firing of even one machine gun slows down the pursuit immediately. Generally speaking, the danger was, therefore, less the recognition of the withdrawal by the enemy during x-night, than recognition during the preceding days. In the latter case, the enemy could prepare the pursuit, and could particularly bring up tanks in time. This would have provided him with a good chance for breaking through Position One before the defenses were properly prepared. Antitank teams were placed at all paths as well as corduroy roads. At thus stage, the division did not as yet have its own tanks. By the evening of x-day, the heavy antitank weapons were already emplaced in Position One.

In short, Chapters B and С provide the following conclusions:

1. Withdraw the greatest possible number of forces up to the evening of x-day, despite the risk of weakening the front.

2. Use these forces for the preparation of Position One for defense.

3. Concentrate efforts on concealing the withdrawal in the days preceding the evening of x-day.

4. Avoid fighting, except for necessary local defense, during x-night in front of the rear position.

D. Fighting in Position one.

Without enemy interference, the division withdrew to Position One during x-night. Only parts of the telephone lines of the rear guard had to be sacrificed.

1. Advanced positions. The covering positions now became, from the tactical point of view, advanced positions. The enemy moved up after dawn, advancing hesitantly on a broad front. During the early afternoon he probed the advanced positions, and subsequently attacked them with stronger forces. He was repulsed successfully. The artillery had a special share in this defensive success. All batteries, including those not located between the advance positions and Position One, maintained radio contact with observers in the advanced positions. The entire day was thus gained for defensive preparations in Position One. In the evening the division was faced by the difficult decision whether to maintain the advanced positions for another day. The success of the above-described defensive action, and the desire to gain additional time before the enemy could attack Position One, favored holding on for another day. After all, the situation in the division sector did not authorize the commander to set the time for withdrawal from Position One. On the other hand, there was the likelihood that the enemy would renew and increase his attacks on the following day, and penetrate through the gaps between the advanced strong points,, Thus there was the danger that the strong points might be encircled and isolated, belying on the experience and fighting qualities of the troops, the division commander finally decided not to abandon the advanced positions. The fact that the broken terrain permitted withdrawal even by day was an additional argument in favor of maintaining the advanced positions. Only the artillery stationed between the advanced positions and Position One was withdrawn behind Position One. The next day passed, as expected, with renewed stronger attacks against the advanced positions. One strong point was by-passed and, before this was recognized, attacked from the rear, and wiped out. The other strong points withstood the attacks until about noon. Fighting a delaying action, their complements then withdrew to Position One. Thus it happened that the enemy reconnaissance patrols did not probe Position One until the late afternoon of the second day. A larger, organized attack was, therefore, not to be expected before - at the earliest - the morning of the third day. On the other hand, we had lost the men who had occupied one strong point. This shows that withdrawal from the advanced positions during the evening of the first day would have been the better course. It was more or less a fortunate accident that the enemy did not take better advantage of the situation, and did not deal similar blows to our other advanced strong points, excessive demands on troops too easily achieve the opposite of the desired result, and affect the overall situation unfavorably.

2. Reserves. Highways of advance and roads always furnish the stage for mobile warfare, the very type of operation with the resumption of which - though on a limited scale - we are here concerned. This principle has been clearly demonstrated in the course of our own attacks in Poland, France, and Russia. For that reason, we strengthened especially the points where roads and paths led through the defense lines of Position One. The enemy's probing of our defenses gave us no clue as to the direction of his main attack. The long, marshy stretches were left less densely occupied. Moreover, in the initial stage our defenses in the main battle position, in contrast to the VELIZH position, were not yet deep, particularly because of our limited forces. For example, most of our heavy machine guns were placed u the front, not in depth of the position as at VELIZH. This was not too serious, because during these first days the enemy could not yet employ the overwhelming and crushing power of a heavy artillery barrage. The required quantities of ammunition had not been brought up yet at this stage. In this situation the rule about reserves, described in Part I, Section С 3, did not apply. Here the division needed a tactical reserve of at least battalion strength, assembled behind the center of the front so as to be ready for commitment at any threatened point, Each regiment required an additional reserve of at least one company. These reserves could be withdrawn because the division sector had been narrowed and no defenses established in the depth of the position. This procedure was thoroughly satisfactory. In the course of the next five weeks of fighting, one of the main tasks of tactical leadership was the forming of new reserves every evening for the next day's fighting.

The attack expected for the morning of the third day did not materialize. Enemy artillery laid intermittent harassing fire on the main roads; rather strong combat patrols advanced toward our positions, and were thrown back. In the afternoon, the coordinated attack developed, with the main effort- as expected - along the roads, but at no point did it reach our lines. Several tanks were destroyed. The position, like that of VELIZH, was located in terrain interspersed with considerable stretches of swamp and forest. This enabled us to concentrate the few available heavy antitank: guns in the areas well suited for tank warfare. However, it became clear even during that engagement that successful defense and withdrawal to the next position would be impossible without a reserve of tanks. The requested tanks joined the division in the next intermediate position.

Attacks during the fourth day, launched against the same points as during the previous day, lacked again the necessary punch for penetrating our position. However, the use of reserves, including parts of the division reserve, became necessary. Mo reinforcements arrived, and every additional day of combat meant, therefore, a heavy burden for command and troops. The fifth day brought a surprise, and the situation became extremely critical. For three days the enemy had attacked along the roads without success. Naturally, the division was prepared for similar action on the fifth day. However, the enemy surprised us, t.nd attacked part of the forest positions. Using large numbers of infantry, he broke through the position and surged into the rear area, while at the same time keeping the previous points of attack under artillery fire. After this break-through, we fought the enemy in the forest as well as in open terrain. The commitment of all available reserves and the displacement of the artillery, which fired partly point-blank, enabled us to restore the situation by evening, though a salient remained in our lines at the point of penetration. We would have been able to master the critical situation much faster had we had a tank battalion at our disposal. Because of the wooded terrain, the enemy did not use any tanks. After this fifth day of fighting, withdrawal of the division to the next intermediate position was indicated. However, this was not done. We awaited the next morning with anxiety, but contrary to expectation the enemy remained relatively inactive on the sixth day. His infantry troops had suffered considerable casualties, so that he had to regroup for new attacks.

The further withdrawals were made in similar fashion, and I sh.ill not describe them in detail. In conclusion, I present the following summary of fundamentals deducted from the experiences in these engagements:

E. 1. Advanced positions.

Experience has shown that, after withdrawal, the enemy will attack the new position with strong forces at the earliest after one day, at the latest on the third day. Once the enemy attacks, it will depend entirely on the relative strength of defender and attacker how long the position can be held. The tactical means of gaining time (advanced positions) are exhausted at this point. The struggle for time either has taken place before, or else will occur during further withdrawal. Here again it will be waged with the aid of advanced units. The greater the distance covered by the withdrawal, the better is the opportunity for advanced units to withdraw gradually in order to delay the approach of the enemy to the main position. If these units are more than four kilometers in front of the position, they must be proportionately strong, and equipped with their own mobile artillery and, if possible, with tanks. The disadvantage of weakening the main battle position by assigning men and equipment to the advanced positions is more than made up by the gain of time. Therefore, advance units are to be used especially where the old and the new positions are far apart, and where the intervening terrain contains dominating heights with good visibility. These conditions did not exist to a sufficient degree in the terrain between VELIZH and Position One.

2. Artillery: Mobile artillery was another decisive weapon in this straggle for time, A daily requirement was the displacement of batteries and the moving of observation posts in order to allow massed artillery fire at threatened points. Luring this first stage, when the enemy attacked a new ana unfamiliar defense line, he could not yet lay down the kind of barrage used during a large-scale attack in position warfare. Thus our own artillery had a much better chance of breaking up enemy infantry attacks. For fire control, radio traffic was permitted. Only flexibility in the use of observation posts placed anywhere up to the most advanced lines assured success. In this situation, emphasis was placed again on the principles of artillery operations in mobile warfare.

3. Tactical reserve. In addition to the displacement of artillery, the organization of a tactical reserve was an essential element for the successful command of the division. It had to consist of infantry, engineers, and tanks.

4. Fighting in woods and swamps. The enemy attack in the wooded sectors demonstrated his natural ability - which he successfully exploited - in fighting in swampy and wooded terrain of limited visibility. The enemy chose swampy terrain particularly when he wanted to press an attack before he had brought up heavy weapons, artillery, and sufficient ammunition. Attacks of this type were made with large masses of infantry which were always at the disposal of the enemy.

One episode taken from the fighting in a position farther to the rear should clearly illustrate this method of fighting.

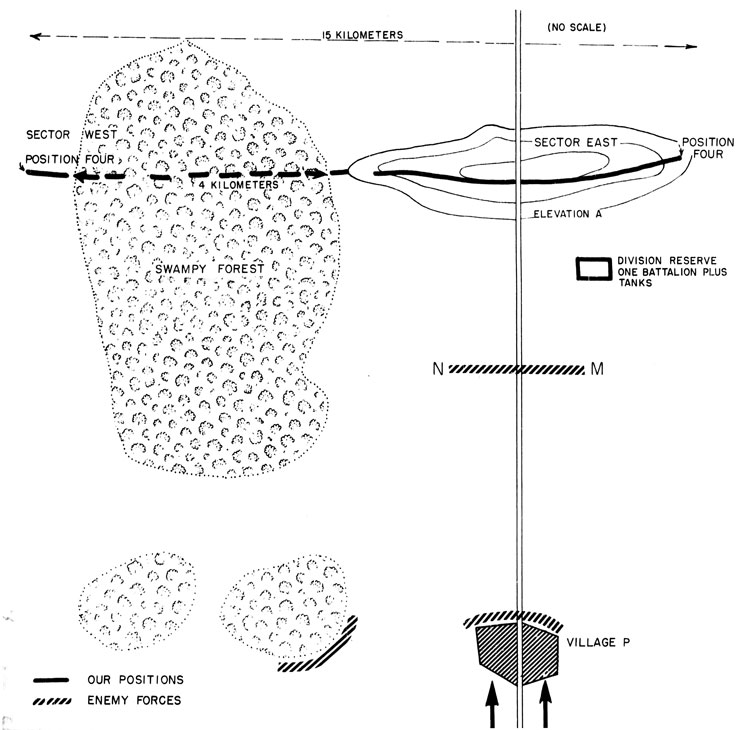

Initial situation (see sketch 3)

SKETCH 3. ENEMY ATTACK IN THE WOODS

The right wing of the defense position (Sector East) was on high, open ground, especially suited for defense. An improved highway leading through this terrain was the only traffic artery in the entire vicinity. A dense and swampy forest of about three to four kilometers width adjoined Sector East on the left. Then followed open terrain (Sector West).

Subsequent tactical development

On the second day after occupation of Position Four, the enemy attack against the elevated position of Sector East began, supported by about twenty tanks. The attack was repelled by our own artillery fire which disabled most of the tanks. However, it was impossible to establish any kind of contact with Sector West on the other side of the swampy forest. The company assigned to covering the forest reported time and again that the swamps were impassable, and that, as a result, no unbroken defense line could be organized, and no contact between the two sectors established. Neither the assignment of engineers as reinforcements, nor a reconnaissance conducted by the battalion commander on the third day provided a solution for the closing of this gap in the forest. In the course of the third day, the enemy made further, unsuccessful attacks, mostly against Sector East. The same evening, after darkness, the division's assistant adjutant on his way to the command post of Sector East encountered enemy troops near village P, The road was blocked. Immediate reconnaissance revealed enemy troops with heavy infantry weapons near village P and in the woods to the west. The division reserve (one battalion and the tank battalion) had been moved to the most threatened sector, namely Sector East. It was our estimate of the situation that the enemy had traversed the swampy forest in unknown strength in order to penetrate into the depth of our position while reinforcements were brought up, or else to roll up the front of Sector East from the rear. The situation was especially critical because the entire supply of our division and of the division on our right depended on the blocked road. Quick action was indicated, since no other communications existed in the sector, orders were issued by radio as follows:

1'he division reserve (one battalion plus tanks) will attack along the road in the direction of village P. The attack will be executed without consideration of an expected, renewed enemy attack against our elevated Position A. Simultaneously an attack with weak forces will be launched from the south.

H-hour was set for 1700, at dusK. The division faced the difficult task of freeing forces for the attack from the south, and bringing them up in time. By 1600 we had succeeded in having two companies with three assault guns ready south of village P. In short order we drove the enemy from village P and the forest to the west. Continuing their advance in northern direction, our companies approaching line il-N encountered much stronger enemy forces with numerous heavy weapons. Only the attack from the north was able to clear the road with the aid of tanks, and restore the situation. A real battle had developed, which ended with the annihilation or capture of the enemy troops. It turned out that simultaneous with our withdrawal to Position Four, enemy troops had followed us through the forest in which we had been unable to establish contact between Sectors East and West. The enemy had remained in hiding in the forest until the evening of the third day, and during that time had received reinforcements. During the evening of the third day the enemy then occupied the positions shown in Sketch 3. His forces consisted of two infantry regiments with their heavy weapons, plus some light antitank guns. The епеmу intended to attack Sector East from the rear, while elements near village P were to protect the operation against interference from the south. In contrast to the preceding days, this critical fourth day was cot marked by en enemy attack from the north against Position East. The annihilation of two enemy regiments presumably was one of the reasons why no further attacks on Position four followed. This episode demonstrates the ability of the enemy to take advantage of every terrain feature; it also demonstrates the effectiveness of quick, decisive action on our part.

D-133