Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

JAPANESE IN BATTLE

First and Second Edition, 1943, 1944

ENEMY METHODS

JAPANESE IN BATTLE

1st Edition

GENERAL HEADQUARTERS, INDIA

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE DIRECTORATE 4/G.S.I. (t) MAY 1943

THIS DOCUMENT MUST NOT FALL INTO ENEMY HANDS

FOREWORD.

The Japanese are an island race who have mastered the art of war, not through any mysterious or indefinable quality inherited from their Emperor, their islands, or their ancestors during your grandfather's time they were still in the bow-and-arrow stage—but through serious study of ancient and modern methods, and by intensive training. If we analyse their tactics, reducing them to fundamentals, all that they practise is to be found in our own training manuals, or in the military histories of ancient campaigns ; not even the snipers in the trees are new— the jungle tribes of Africa and Brazil have employed them since time immemorial.

In their long history the peoples of our Empire have shown the world that they possess more than an average share of courage and tenacity, and today we must add to these advantages our undoubted superiority in arms and equipment. Any success which the Japanese have had against us was due to intensive training, carefully rehearsed plans and normal guts. Whatever the task in hand—be it the digging of a single fox-hole or the preparation of a large-scale invasion—their work is done with meticulous care, and by intensive and sustained training alone can we hope to outmanoeuvre them.

This pamphlet is largely the work of soldiers and airmen fighting in Burma and the South West Pacific who, in notes, sketches and photographs, have recorded their observations of the Japanese in Battle.

Special acknowledgement is due to the American Marine Liaison Officer of the Pacific Ocean Areas whose appreciation of Japanese characteristics and methods has been quoted in Chapter I, Section 2. Acknowledgement is also due to our Allies for the drawings reproduced as Examples 13 and 15 in Section 4 of the Chapter on Defence.

Part II, which is devoted to the important subject of counter measures, is being prepared by the Military Training Directorate, G.H.Q., India Command.

CHAPTER I. GENERAL

1. Morale.

"When I received my mobilization orders, I had already sacrificed my life for tny country. . . .you must not expect me to return alive "

1. This sentence is quoted from a letter found on the body of a dead conscript. It is by no means exceptional and indicates a fanatical conception of service which finds expression in a disregard for personal safety and a readiness to fight to the last man and the last round. The morale from which such feelings of self-sacrifice spring, is based on an attitude of mind assiduously cultivated from a very early age.

Japanese moral training instils a strong religious belief; " Comrades who have fallen !" reads what is almost the last entry in a soldier's diary, " Soon we shall be fighting our last fight to avenge you, and all of us together, singing a battle song, will march to Kudan ". (Kudan is a shrine near Tokyo dedicated to the war dead). The second pillar of Japanese morale is deep personal devotion to the Emperor. The last blood-smeared page of a diary captured in Burma has " Three cheers for the Emperor " scrawled across it. The Army belongs to the Emperor and its mission is his divine will. Finally the Japanese believe they are a chosen people, a superior i-ace. Such is the basis of a morale to which is closely allied a high state of individual and collective battle discipline.

All this does not mean that the Japanese are immune from fear and defeat* By a different process they have reached that stage of fanatical self-confidence which the Nazis reached in 1939. " We are a superior race with a divine mission. We are invincible ". These are the foundations of sand upon which Germans and -Japanese alike'have built their morale, and the initial military successes which both these countries achieved against their ill-prepared enemies gave ample credence to the lie of invincibility. But the Nazi no longer goes into the attack making the Hitler salute or with " Heil Hitler " on his lips, and his arrogant self-confidence, subjected to the growing armed might of the United Nations, is crumbling. And so with the Japanese ; faced with the example of Germany and the just retribution which will most assuredly overtake them, they cannot hope to maintain a morale which is based on the fallacy of invincibility and a divine mission. Even now (May 1943) when our main effort is still confined to Europe and North Africa and the situation is more favourable to the Japanese than it can ever be again, we find that the desire for self preservation can at times be stronger than the desire to stay and fight it out. To quote from a recent situation report—

"After a fairly quiet night the enemy attacked the 1 Punjab posns from the North. No ground was given, but the feature known as the Pimple, not previously occupied by us was occupied by the enemy.... a counter attack was put in by a coy of 1 Punjab and a pl of 15 Punjab with the bayonet. It was completely successful and drove the enemy off the Pimple and out of the village. The enemy retreated across the open country NE where they were caught by our arty..."

Our counter attack cost the enemy about 103 killed, of which 73 have been checked over not counting those killed and wounded by our arty...."

A prisoner of war describing the action said—" The fire fight developed in earnest at about thirty yards range and then the bayonet charge which followed completely overran our position. I was wounded twice in the chest and before losing consciousness saw my comrades beat a hasty retreat ".

In conclusion a statement made by a Japanese recently captured in the Arakaa is worthy of note. He volunteered the information that our shelling and bombing ihad caused, besides shell shock, several cases of nervous prostration.

2. Tactical Characteristics.

2. To quote from an American appreciation : " Japanese tactics in general are

based on deception and rapid manoeuvre. They will go to extremes to create falsa

impressions. Sheer weight of numbers and steam-roller tactics are apparently

distasteful to them, as they lack finesse, though such would probably be used if

required. One gets the impression that the perfect solution to a tactical problem is

a neatly performed strategem, followed by an encircelment or a flanking attack

driven home with the bayonet. This allows of the commanders to demonstrate

their ability and the men to show their courage and ferocity in hand to hand

fighting. Their plans are a mixture of military artistry and vain-glorious audacity ".

" Deception, strategems and ruses must be expected at all times. Bull-dog tenacity in carrying out a mission, even to annihilation, will very frequently give a most erroneous impression of the Japanese strength and will often result in small forces overcoming larger ones, as their units are not rendered ineffective until they are nearly all casualties ".

" This capacity for driving on despite losses is not only displayed by officers. Training for the Japanese has been so thorough that every man will keep plugging until his own part of the main mission is completed. Long experience has taught even the privates what must be done before a mission is completed, and discipline, lack of imagination, and fatalism, drives them on despite losses.

"To the Japanese leader, tactics is an art, with decisions gained by skill, not by sheer power. Their policy for the use.of manoeuvre may appear to lead towards complicated evolutions. Training and the delegation to subordinates of the initiative for independent action are most probably the factors that make such tactics simple ".

3. The Principles of War.

3. In the second edition of Japanese Military Forces it was stated that the principles of Surprise and Mobility characterized all Japanese land operations. To these must undoubtedly be added the principle of Offensive Action.

4. Surprise is achieved in both strategy and tactics and ruses are extensively, employed. Approaches through country regarded as impassable and the conduct of operations during foul weather are means by which troops more sensitive to ground and climate have been placed at a disadvantage. The fifth column has been freely employed, and with their aid it has been possible greatly to increase the methods by which the enemy can be taken by surprise.

Ruses include the use of disguises, calling out in the language of the troops opposing them and feigning panic and disorganised withdrawal. This last ruse may be accompanied by strewing the line of withdrawal with stores and equipment— all carefully covered by concealed machine guns.

5. Mobility, which is achieved in a number of ways, has been one of the most

important factors in obtaining surprise. The ability to exploit to the full the

exceptional marching powers of the troops—they are capable of covering thirty or

more miles per day—is closely allied with the ability to feed them. They may, by

chosing a circuitous path through difficult country, attempt to overtake and cut the

line of retreat of a force withdrawing along a road, but mobility does not end there;

if the chances of living on the country are small troops may carry as much as seven

days rations with them thus freeing themselves during this period from the encumbrance of an administrative tail. Impressed local inhabitants, with carts if the

country is suitable, supplement their carrying powers, whilst opportunities to seize

local supplies are never neglected.

The Japanese soldier has been trained to carry up to 58 lbs., which is what Napoleon's troops carried when they marched to Moscow—but their total load included 15 days rations ! Lest either of these loads should be thought exceptional we should not forget the British troops in the Peninsular who carried about 60 lbs. and those at Mons in 1914 who carried only a few pounds less.

It should on no account be construed from this paragraph that the Japanese habitually carries a heavy load of rations and equipment, for like us he prefers to fight as lightly equipped as possible, but the pointworthy of note is that if several days' mobility can be achieved only at the price of carrying a load of rations on his back, he is prepared to carry itr

About our own mobility the Japanese have stated " Although the English Army has some mechanical mobility, in general it does not have much manoeuverability "

6. Offensive Action is described in one of our training pamphlets as a principle which gives moral superiority and, tends to confer the initiative and, with it, liberty of action. A famous British general recently simplified it thus " The object of every soldier will be to kill Germans ", and this is very near to the Japanese interpretation for the latter applies the principle of offensive action not only to his attacks but also situations in which his defeat is a foregone conclusion. Whatever the situation his object is to kill the enemy. " If only I can die killing six or seven of the enemy instead of by his first onslaught " writes a diarist just before the last attack is made by a small party.

In August 1942 American marines raided an island held by about 90 Japanese. The raid was a complete success and most of the garrison were annihilated. The remnant, however, estimated at about a dozen, attacked the raiding party as it was leaving the island and thus suffered further casualties. It is an interesting example of offensive action in desperate circumstances.

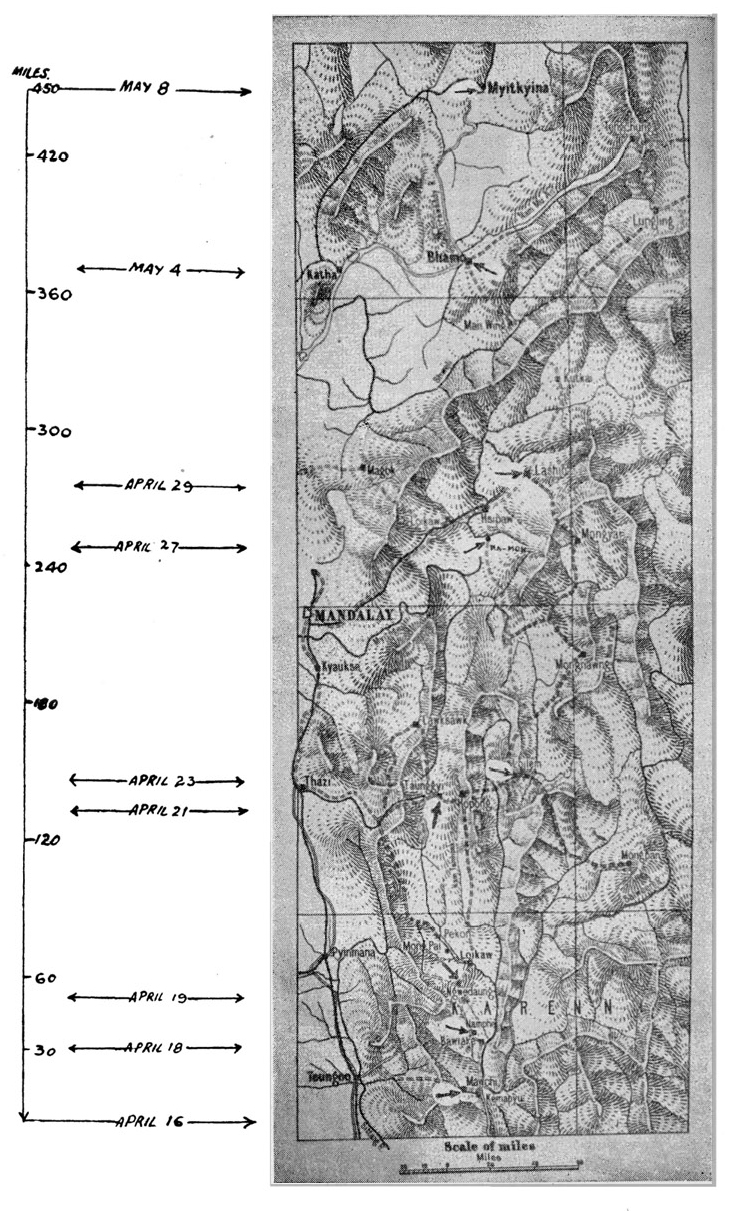

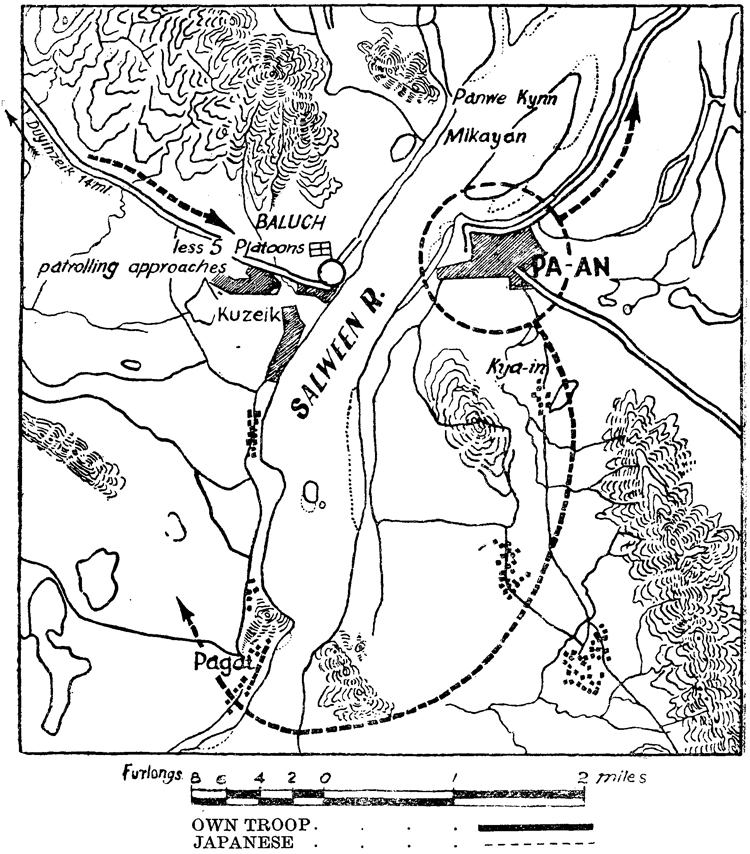

4. An Example of strategic mobility.

An outstanding example of strategic mobility on the part of the Japanese was their advance through the Shan States from Karenni in the South to Myitkyina in the North, a distance of some 450 miles, covered in three weeks. This feat is even more remarkable when it is realised that during their advance the Japanese fought three not inconsiderable engagements and were hindered by numerous delaying actions.

In early April 1942 the Japanese forces, consisting of the 56th Division, advanced northwards between the Salween and Sittang Rivers and occupied the town of Mawchi. Facing this advance the Chinese disposed four battalions in depth along the road Mawchi-Loikaw.

On April 17th, the Japanese, having made unsuccessful frontal attacks against the Chinese, by-passed the position and cut the road between Bawlake and Namphe, reaching the town of Namphe on the following day. Here, there was heavy fighting but the enemy overcame all opposition and pushed on another 20 miles, reaching Ngwedaung on the morning of the 19th.

Two days later, on the evening of April 21st, the Japanese had occupied Taunggyi, having carried out a large scale encirclement of the Chinese positions-Loilem, a town some 40 miles away, was their next objective, and this they captured on April 23rd after by-passing the Chinese, who had taken up defensive positions along the Taunggyi-Loilem road.

In the next four days the Japanese force pushed on another 120 miles, reaching Na-mon on April 27th. Two days' heavy fighting ensued, but the enemy succeeded in maintaining their advance and pushing the Chinese from Lashio, to positions at Kutkai some 40 miles northward. Once having succeeded in ejecting the Chines© from this position, and having surprised the force holding the bridge over the Shweli River at Man Wing, no further organised resistance was offered to the Japanese advance. As a result Bhamo was entered on May 4th and Myitkyina was occupied four days later, on May 8th.

DISCUSSION.

The maintenance of a daily average advance of some 21 miles despite delaying actions and despite having to fight battles speaks for itself as an example of strategic mobility.

In considering how this advance was achieved the following points are outstanding. :—

Firstly, the skill of the Japanese in the choice, direction and execution of their encircling movements which, probably more than any other single factor, accounted for the speed and great distance of withdrawals the Chinese were compelled to undertake.

Secondly, the refusal on the part of the Japanese to be deterred from their primary objective by threats to flank or rear.

Finally, there is the ability of the Japanese to move without a cumbersome administrative tail.

5. Orders.

7. Japanese operation orders are often extremely brief. The general absence of detail suggests that battle has, where possible, been reduced to a drill. In the large number of captured orders available for examination little reference is made to frontages, dividing lines, or supporting fire; this is because Japanese units are generally given clearly defined features as objectives while artillery is placed under the command of units or even sub-units and may fire by observation at targets of opportunity.

In Chapter XII of the second edition of Japanese Military Forces examples were given of an order for the advance to contact and an attack order. Below are three orders for the defence, the first two, which are more in the nature of instructions, are extremely brief, the third is in some detail and it was accompanied by a sketch ; the •ketch has not been reproduced.

Example 1.

HORI Order No. A-137 South Seas Detachment Order

6 Nov. 0900

ILIMOW

1. Since yesterday (5th) morning YAZAWA Unit (BUTAI) has been attacked by approximately one enemy battalion which was repulsed. Since last evening, security unit (BUTAI) of KUWADA Battalion has been attacked by a small number of enemy, which were repulsed. The situation at the rear of the enemy line is not clear, but troops seem to be there.

2. The Detachment will consolidate the key point along the road to the south of ILIMOW.

3. One Coy. of the YAMAMOTO Regiment (less 1/3 2 M. G., 1/2 P, casualties collecting detachment unit, No. 3, portable wireless attached) shall depart from its present position immediately, followed by the main body, and proceed to BAIBARI and consolidate the key points in the vicinity of said place.

4. YAZAWA Regiment is to carry on its present duty.

5. I will be at ILIMOW.

Detachment Commander

HORI, Tomitaro

Method of distribution :—

Summon Lt. Colonel TSUKAMOTO and issue it verbally. After it has been sent to Colonel YAZAWA by telephone, it will be issued verbally, to be written down.

Example 2. HORI Order No. A 316.

South Seas Detachment Order 0600 3 Nov. PAPAKI.

1. According to the reports from YAZAWA Unit (BUTAI), a portion of the enemy is now advancing toward the vicinity of KOKODA and ISURABA road south of FUKURAKUHI (T. N :—FUKURAKU-tombstone or monument. This may be the name of a place) A part of YAZAWA Unit (BUTAI) was attacked last evening, but repulsed the enemy.

2. A part of the detachment (SHITAI) will protect the rear of the left flank in the vicinity of ILIMOW.

3. The YAMAMOTO R (T. N :—Regiment) will occupy a position in the vicinity of BAIBARI, 6,000 kilometers south of ILIMOW, with its main strength (3rd. Bn.) in order to protect the Detachment's left flank YAMASAKI Engineer platoon will assist.

4. YAZAWA R is to carry out its present duty. No. 88 Wire Company of HOZUNI unit H.Q. is released from the detail.

5. I will be here.

Detachment Commander :— HORI, Tomitaro.

Method of distribution:

After substance is sent to YAMAMOTO Unit (BUTAI) Commander by runner or radio, verbally issue to the order receivers for their notes.

Example 3.

SECRET

Order No. 5 for No. 3 Company of KURE No. 3 Special Landing Party— August 17th 1942, at KAVTENG Company Headquarters. Commander of

No. 3 Company, Kure No. 3 Special Landing party, MARUYAMA JUNTA.

Order for No. 3 Company.—

1. Enemy situation.—The enemy appeared in the seas near the Solomon Islands with powerful operational units, and a large number of transport ships, opening an attack against position " X " at daybreak of August 7th.

2. Situation of our troops.—No. 1 Coy. has despatched sentry groups and is in the midst of constructing defensive positions on the plateau south of the pasture in the PANAPEI district, and on the seacoast of PANAPEI.

3. Company Commander's Decision.—This Company, following the secret operational Order No. 17 of KURE No. 3 Special Landing Unit, will construct defensive positions along the coastline of the Seaplane Base south of NUAN and perfect the defensive preparations against the ocean front.

4. (1) No. 1 Platoon Commander will direct his own. platoon, the H.Q. Platoon, and No. 2 Platoon (all members except those on duty), and must quickly construct defensive positions as designated.

(2) The HQ Platoon Commander, and the No. 2 Platoon Commander will place under the direction of No. 1 Platoon Commander the necessary number of men required during the construction of the positions.

5. Distribution (disposition) of troops on the ocean-front as per attached map

No. 1.

(1) Nos. 1 and 2 Platoons (To each will be attached one quick-firing gun, one heavy machine gun, one light machine gun, one heavy grenade discharger) the first line. Positions No. 2, No. 1 Platoon, Position No. 1 and No. 2 Platoon. The Q Platoon, reserve unit.

(2) The HQ Platoon Commander must lay telephone lines between the 1st

and 2nd positions. (In case there is more than 2 distribution of positions).

(3) The Front Line Platoon Commander will diligently strengthen defensive

(defence) positions in the area under his charge, clearing the field of fire so as to give

maximum fire power, and facilitate speedy movements of troops.

It is also necessary to take strict precautionary measures in the flank and rear.

6. Distribution (disposition) of troops on the Land side, is to stand by at the

Company Headquarters.

7. Orders for commencement of movements of various units will be given later.

Particulars of Commands.

1. Alarm Call.—(Landing Unit Assembly Call) by bugle call (Landing Unit

Assembly Call) or by verbal orders (messengers).

2. Personnel.—All members except those on duty. (Even those who are unable

to participate in the actual battle on account of illness, must arm and stand by at the

'Company Headquarters).

3. Assembly Point.—East side of the Company Headquarters.

4. Armaments, and ammunition carried by troops—As prescribed by the

Landing Unit. (Reserve ammunition will be loaded in the trucks).

5. Vehicles.—Five trucks (for transporting units and moving men).

One machine gun carrier (for use in commanding and liaison).

One Passenger Car (for use in commanding and liaison).

6. Information, reconnaissance and patrols.

8. The Japaneseadvanced into Malaya and Burma using reproductions of British Ordnance Survey maps upon which Japanese translations had been super-imposed. The information which these maps provided was supplemented by a detailed study in peace time of the probable area of operations. This study involved the " planting " of commercial photographers in places of operational interest and other forms of " economic " penetration the primary task of which was espionage. Consider able success was also achieved in organizing the fifth column through which it was possible to continue the collection of information after photographers, barbers, tatoo artists and all the other Japanese who had found their way westward, had either left hastily or been interned. With fifth column assistance it was possible to obtain up-to-date information on dispositions and defences and during mobile operations to direct aircraft onto headquarters and other suitable targets.

9. During the early days of the war in the South West Pacific and Burma, the Japanese often subordinated reconnaissance to speed of advance; Frontal attacks were launched against imperfectly known positions and bold decisions were taken even where information was lacking. The initial offensive had succeeded and whatever the cost the momentum was to be maintained; the operations evolved themselves into one vast encounter battle in which the Japanese, having siezed the initiative sought to maintain it. As resistance hardened, however, their attention to reconnaissance became once more evident and operations in Burma in particular show an intimate topographical knowledge which could only have been obtained by extensive patrolling and by the employment of local inhabitants as guides.

10. The use of small patrols in a purely reconnaissance role has often been

reported. According to the nature of the country and the task involved these

patrols may either remain in observation in one place or make a reconnaissance

involving a march of several days during which they are entirely dependent on what

they carry themselves. Patrols of this nature often consist of three to six other

ranks commanded by an officer or N. C. 0. They will often be in local civilian dress.

Reconnaissance reports are frequently accompanied by sketches the general standard of which is high. If it is considered that the task involved does not warrant the employment of a patrol a couple of scouts may be used instead. Their tasks may be to lie in hiding near our positions and observe.

11. Fighting patrols vary in strength, but a platoon or less is commonly

employed. In Burma the activities of these patrols have been confined almost

entirely to the hours of darkness, the exception being when they have been sent

out by day some distance to a flank—sometimes with the object of seizing local

herdsmen for interrogation.

The tasks of troops patrolling at night vary from drawing fire in order to discover our positions, to determine raids in which attempts are made to overwhelm small posts. Drawing fire is, however, by far the most common activity.

12. Reports from New Guinea describe how once, strong patrols (30, 60 or 120, are the figures quoted) were employed by the Japanese whose " movements were similar to those of troops in an encounter." It is clear from the account given, that these were small aggressive detachments which advanced along jungle tracks until they made contact with our troops ; they then endeavoured to hold them frontally whilst sections or platoons tried to outflank them through the jungle. It is possible that such offensive action will be taken by patrols covering the occupation of a defensive position.

7. Training and rehearsals.

13. In peace the Japanese train for war. In war they train for important operations. The severity of their training is worthy of note, and the following extracts from reports by officers who were attached to the Japanese Army before the War give some indication of the thoroughness of their preparations :

" The autumn manoeuvres of the Guards Division took place in the first halt of November in the mountainous region round the semi-active volcano Mount Asama about a hundred miles northwest of Tokyo.

The weather was extremely severe, the temperature well below freezing point in the daytime and considerably colder at night, with snow, rain and high wind. "... .According to the plan of the directing staff, a defensive position should have been occupied the following evening.... but owing to the ice and snow the mountain roads had become dangerous for horses and vehicles so that part of the scheme was called off and the division marched on to the starting area for the next phase, whilst that part which was to form the skeleton enemy marched back over the Torii Pass to their billeting area, arriving at about six that evening surprisingly fresh considering they had marched some seventy miles in forty-eight hours under very trying conditions...."

Another report—

" The march to camp, a distance of twenty-six miles, was done under company arrangements, after the whole Regiment had left barracks together On arrival at camp, after an average of eleven hours on the road, all companies carried out P. T. or rifle exercises before the evening meal. The companies of the battalion to which I was attached had breakfast at 4-30 A.M., lunch at 12-30 P.M. and supper at 5-30 P.M.

A third report—

" A full pack and three ammunition pouches were carried on all training " (This was in 1938. The full weight of equipment carried will have been approximately 58 lbs.)

14. When War comes this tempo is, if possible, intensified—

" August 25th 1942. Get up at 0300 hrs for landing practice. 0400 hrs landed and took up battle positions. 0600 hrs the first fight ended near swamps. Have breakfast. From about 0800 hrs do second attack and defence exercises and then-some sea bathing. Return to ship. From 1500 hrs cleaning of arms and equipment. How busy we are bathing every day fully-equipped. Since formation of unit only 3 hours sleep per day."

Before the attack on Malaya troops trained in French Indo-China carrying full equipment, i.e. 58 lbs. Subsequently they advanced down the peninsular carrying the absolute minimum. The practice of making the troops carry more in training than in actual operations is an old one dating back to the time of the Roman legions.

Operations may be carefully rehearsed ; this does not mean that the Japanese train on a model of the position they will eventually attack, but rehearsals include intensive training under conditions closely approximating those under which they will be required to operate. For example Japanese troops have achieved surprise more than once by advancing through what has been regarded as more or less impenetrable Mangrove swamp. Without careful training this would hardly be possible, and troops are practised in overcoming such obstacles for weeks before they are committed to the actual operation.

Finally an element of surprise is introduced into training as often as possible, and a unit resigned to several weeks routine may easily be woken up in the middle of the night and ordered to move fifty miles at once.

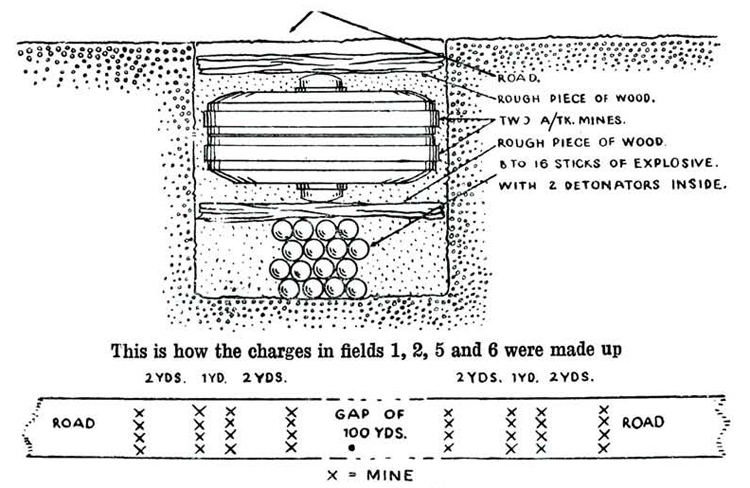

8. Road blocks.

15. The Japanese employ road blocks— to cut off a force retiring, to protect one or both flanks of an encircling movement, as part of a defensive system.

16. As far as possible road blocks are sited in positions where they effectively prevent all movement until attacked and cleared; this is particularly the case in defence when they are most likely to be encountered on defile3 the possession of which is vital to an advancing force. The following sites have been chosen in the past— area of a bridge upon which several routes converged, single road with dense jungle on both sides, centre of a town or village. The exact position may be just over the crest of a rise, or round the bend of a road—in fact anywhere where vehicles will be close upon the road block before drivers can stop or turn round.

17. Roads may be blocked with felled trees or vehicles. Some blocks have been formed simply by firing at point blank range at the first few vehicles to round a, bend or clear a crest. Occasionally roads have been blocked by a series of three obstacles sited at approximately half-mile intervals.

18. A road block position may be covered by a force varying from a small party

with a machine gun to a whole regiment. If not brought quickly to battle and

destroyed small holding forces are often reinforced, until finally the block becomes a

well organized position defended with the greatest determination.

Blocks are normally covered by an infantry gun sited about 50 yards from the block in a position from which it can fire straight down the road. If we are using tanks, the 37 mm. gun must also be expected. At the same time machine guns— light or medium—deny the road to unarmoured troops. Sites chosen invariably include cover on both sides of the road in which troops protecting the flanks of th& road block conceal themselves.

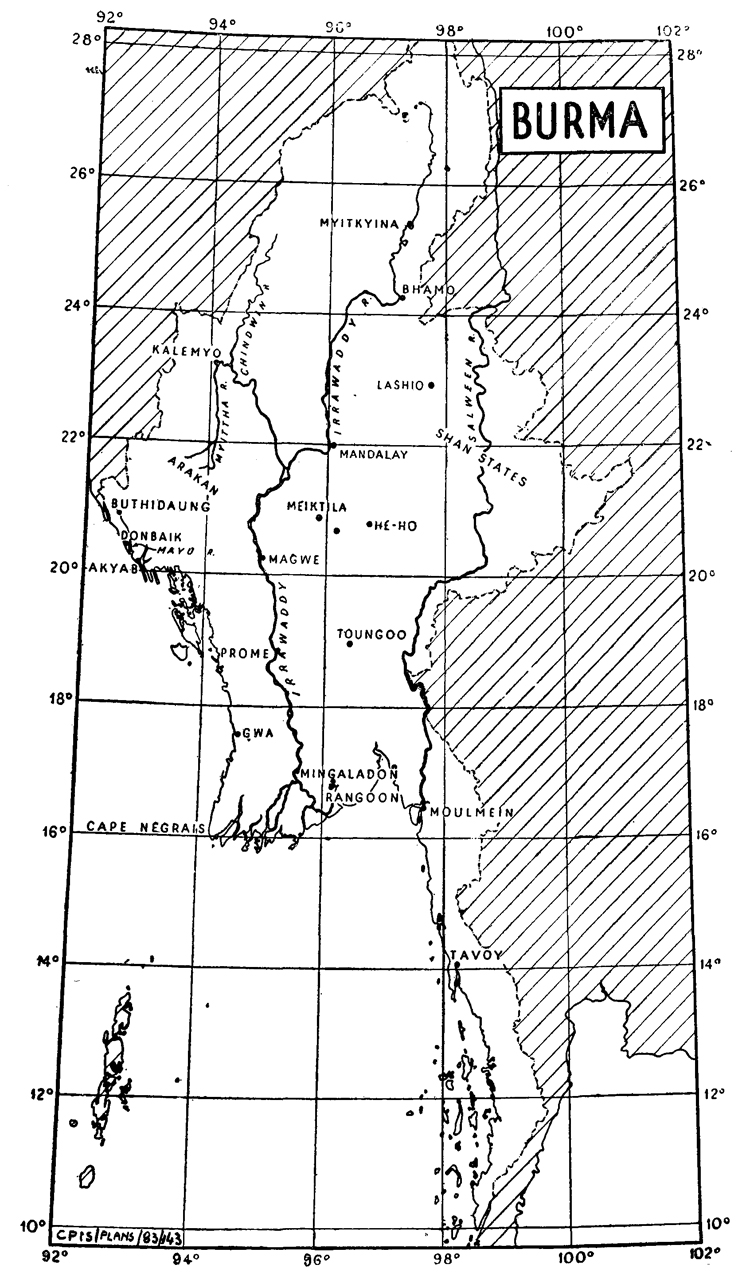

CHAPTER II.—THE COUNTRY YOU MAY FIGHT IN.

1. Part of the Mayu River area, showing the flat plain with occasional nullahs a and wooded hills,

2. Typical of very large areas in the Arakan and the deltas of all Burma's larger rivers, this picture, shows an area of tidal creeks, scrub mangrove and rice fields near Akyab.

3. This picture of the Myittha Valley, south of Kalemyo, gives a good impression of conditions existing over large areas of the undeveloped portions of upper Burma.

4. A beach scene on the west coast of Burma, Similar country may he seen, anywhere between Gwa and Cape Negrais.

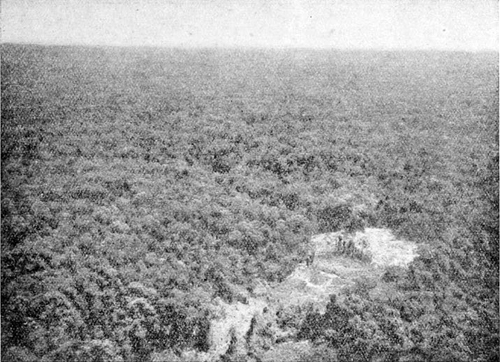

5. A photograph showing typical dense evergreen forest. Large areas of this type are met in the Arakan Yoma and in other areas of heavy rainfall including Upper Burma.

6. Foothills and valley near Buthidaung. Cultivation can be seen on the flat pound, but the hillocks are clothed in scrub. Similar conditions may be experienced throughout Burma between cultivation and hill forest.

7. These paddy fields near Akyab are typical of rice fields in the plains anywhere in Burma.

8. A view of Heho landing ground on the Shan Plateau, giving a good impression of the open, grassy downland encountered over wide areas with an altitude ot between 4,000 and 7,000 feet in the Shim States.

CHAPTER II.—THE DEFENCE.

1. General considerations.

" We must avoid static defence as much as possible. Even when fully on the defensive we must work to keep our forces mobile "—Japanese dictum.

1. Japanese defensive tactics are essentially offensive and mobile, and whilst J apanese forces may resign themselves to being firmly held frontally, the sea, rivers, or thick jungle are no obstacle to the threats which they develop against the flanks of superior forces opposing them. These threats vary greatly in scope: some are made by nothing more than a handful of men who, having approached under the cover of darkness throw a few grenades and fire an automatic weapon at a rear platoon which imagines itself to be a mile or two from the nearest enemy. Others involve a, company or more who, seizing at night a strong natural feature in our rear, disrupt communications and make a general nuisance of themselves until they are attacked und annihilated.

2. " Passive defence " it is stated in an official Japanese document, " has the disadvantage of making it easy for the British to build up their strong fire power ". The Japanese never sit and do nothing ; if the front is quiet it is very probable that a surprise is being prepared on one or both flanks. During operations in Burma this year there have been examples of infiltration up a valley lying parallel to the flank of both forces, a bold advance by a small force along the foot tof jungle covered Mils four miles from our flank, and finally penetration in rear of a flank resting on a wide river, by using boats and landing on a mangrove covered shore. This offensive characteristic is more than a tactical doctrine, it is a deep-seated attitude of mind which will seek expression even in the toost desperate situation. " There are few of us left and we have no arms..." writes a soldier diarist, " but those of us who are left are to carry out a night attack from about 4 o'clock ".

3. The very word " defence "is, whenever possible, avoided. This, for example, was the wording of the intention paragraph of a recently captured operation order for the defence:" The unit will secure its present positions for an advance. While continuing generally to disrupt the enemy's activities it will prepare for future attack ".

4. All through this book reference is made to surprise. In defence it is achieved

by a high degree of camouflage and concealment. Having observed a Japanese

position for two days or more one is forced to ask oneself. " Is it really occupied ? "" Is anyone there ? " " Have they left it and gone somewhere else ? " And one

will seldom know the answer until our assaulting troops are closing in with the

bayonet.

5. Finally the introduction to this Chapter would be incomplete if it did not remind the reader that like a countless host of warriors who built and held our Empire for three hundred years, the Japanese in defence invariably fight to the last man and the last round.

2. Choice of a defensive position.

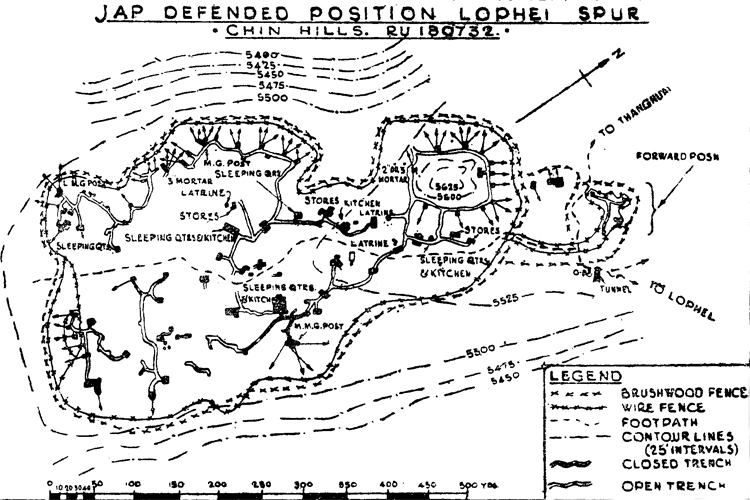

6. In Section 4 appear drawings of various Japanese defensive positions which it has been possible to examine in detail. They vary in size from section posts to battalion localities, and from a study of these and other positions which are still in•Japanese hands it has been possible to identify certain common features—-

(i) Where possible, one or both flanks rest on natural obstacles, such as the sea, n'ivers, creeks and steep hills. (Examples 9 and 10).

(ii) Positions chosen invariably include a natural tank obstacle or a nala which can with, a little digging be made into one, and even though we may have no tanks in "the area of operations, in Burma the possibility of their use has never been excluded when siting a defensive position. When the situation has demanded that localities should be sited where no natural tank obstacles exist, anti-tank ditches have been 'dug (Example 9)

(iii) High ground is invariably strongly held and the Japanese have no qualms -about occupying the crest of a hill, even if its prominence is accentuated by the addition of a pagoda. It will be noticed in Example 5 on page 23 that a trench has been <lug around a pagoda, and weapon pits added.

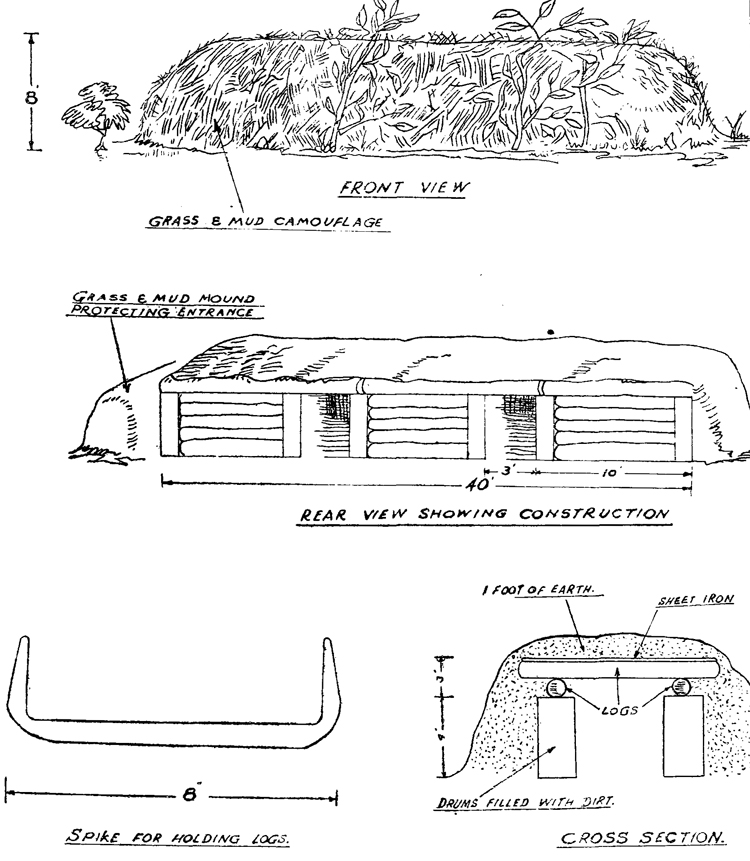

(iv) Swampy ground is not considered an obstacle in the selection of a defensive position and if it is not possible to dig down bunker type earth works are built Up to a height of as much as eight feet above ground level. (Example 14)

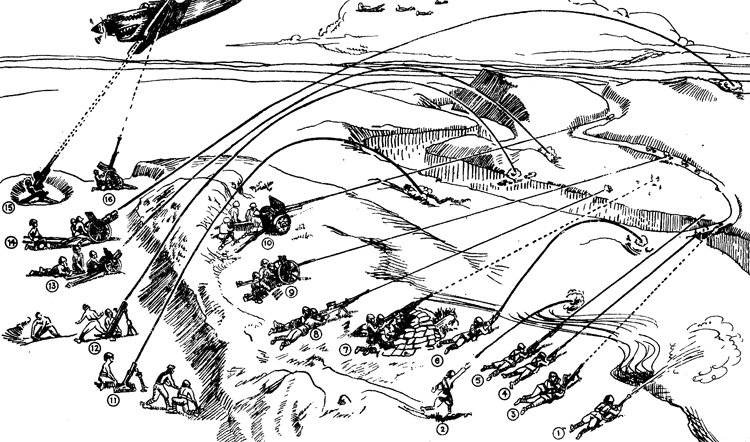

3. Organization of a defensive position.

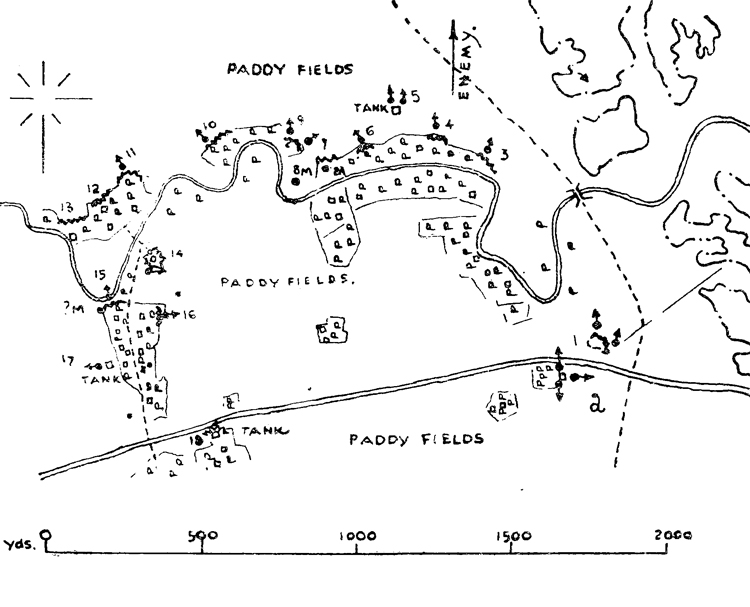

7. If the strength of the forces at his disposal permits, the Japanese Commander occupies a position in depth, if however he is faced with the alternatives of frontage or depth, he appears to sacrifice the latter in order to maintain the former. At Buthedaung one battalion occupied a frontage of 3000 yards (Example 10). Near Maungdaw a force of not more than two companies held a front of 1500 yards (Example 7). The enemy evacuated both these positions before he was brought to battle, it is therefore impossible to say how the defence would have been conducted. It must be assumed, however, that in both cases he was depending on his reserve to deal with any penetration of his front or threat to his flank.

8. The principle of all round defence is not applied as an invariable rule, but given the time to develop a position and the troops to hold it, both all round defence and depth will be achieved. The positions depicted in examples 12 and 13 have been the scene of frequent battles in which ground has been won and lost by both sides. Here, it will be noticed, the principle is strictly followed. Again on beaches where the Japanese anticipate determined attacks, positions are dug and sited to meet an assault from any direction (Example 9).

9. Positions vary in strength from a single sniper up a tree to strong points containing about a hundred men armed with anti-tank guns, medium and light machine guns, grenade dischargers, and perhaps flame throwers and mortars.

10. In British and German manuals stress has been laid on the importance of holding advanced positions, or otherwise denying to the enemy observation of the main defensive position. Isolated section or platoon posts are often found in Burma anything from 300 to 1000 jTards in advance of the general line of foremost defended localities. In some instances they are obviously intended to cover lines of approach (see Examples 10 and 13) and the troops holding them may be expected to fight to the last round and the last man, but other, smaller posts, have been found in thick jungle often sited on small nala junctions ; if these posts are discovered they are usually abandoned. The function of the small post in dense jungle appears to be that of a " hide " from which the garrison can either sally forth as a patrol by night or, by remaining where it is, embarrass any of our own patrols using the nala it overlooks.

11. Alternative positions are dug, whilst the care with which some positions are concealed compared with the total absence of camouflage in others suggest the use of dummy trenches.

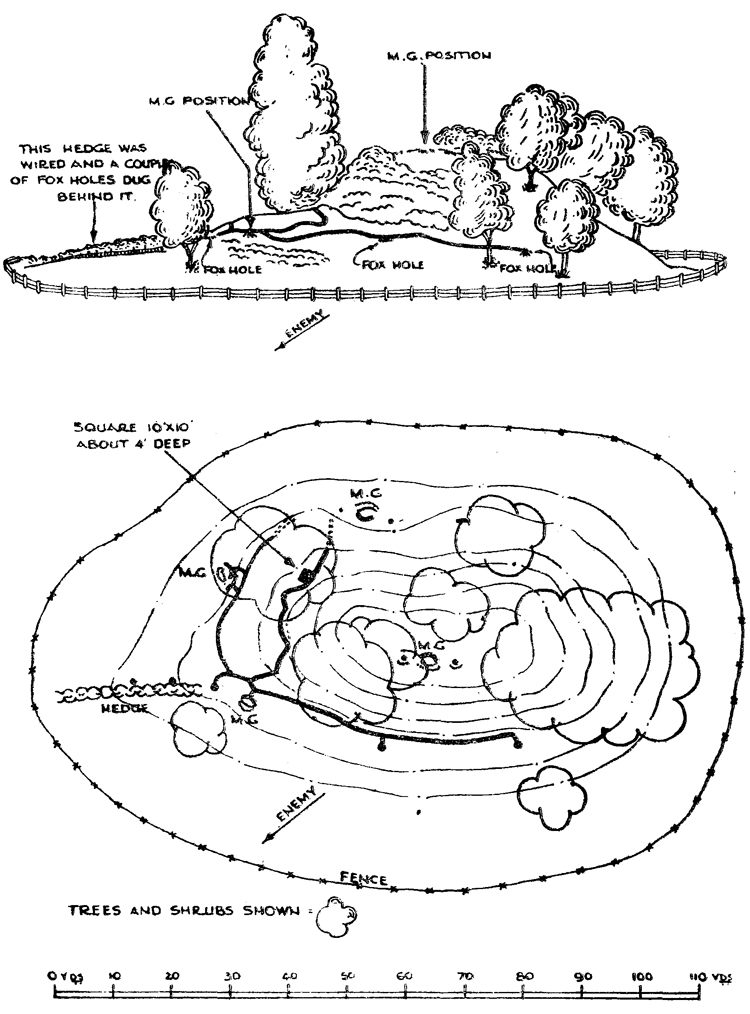

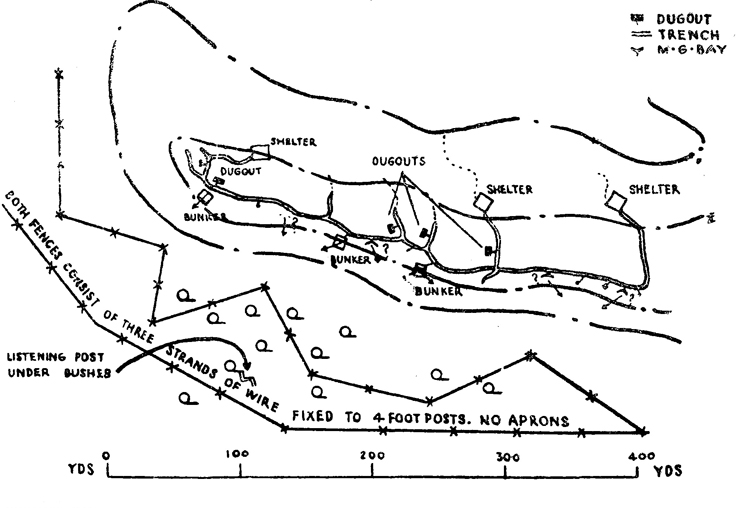

12. Up till now (May 1943) the enemy has very seldom used wire. In the small locality illustrated in Example 4 it will be noticed that he constructed a single three strand fence right around his position. This, however, consisted of captured wire— half barbed and half from the neighbouring telegraph poles—and was a refinement which all other localities in the neighbourhood lacked. If he considers it necessary the enemy uses wire lavishly both on shore and in the sea. An example of a wired position appears on page 26. As distinct from the conventional barbed-wire fence the Japanese sometimes lay a few strands through hedges or single strands at ankle height across likely approaches.

13. The use of steel plates. It has been suggested that one-man weapon pits are fitted with hinged steel lids. There is no evidence to show that this is the case, but it is certain that the Japanese occasionally embody " armour " in their earthworks—either pieces of metal picked up locally or, perhaps, metal sheets brought with them. Recently (March 1943) it was discovered that the turret had been removed from one of our tanks which had been immobilized in a position still held by the enemy and it is possible that this was used to form part of an earthwork. In 1938 steel plates about three feet long and nine inches high were used by the attackers to cover the slits in Chinese M. G. emplacements, but they have been used by the Japanese chiefly in the defence. In the South West Pacific Area they have been reported as being built into the earth and sandbag sides of M. G. and other posts. A pamphlet of field instructions captured at Milne Bay contains the following paragraph on the use of small steel plates. A rectangular steel plate about 3 Shaku by 1 Shaku 5 Sun (i.e., about 1 ft. by 1 ft. 6 ins.) is very handy and has many uses. Placed inside a sandbag position these .plates will stop 13 mm. (i.e., 1/2 inch) bullets. Particularly, on account of the ease with which they can be transported, they can be used for the rapid construction of sniping posts, makeshift positions, positions inside buildings, etc. When taken up to the upper floor or roof-top of a building, they can be stood up against the surrounding walls ; with 2 or 3 sandbags piled up, they will form a strong position.

14. The various types of earthworks will be described in the next section, here it only remains to be said that defended localities are mutually supporting and if a natural field of fire is not available the Japanese cut narrow fire lanes through the jungle.

4. Examples of defensive positions.

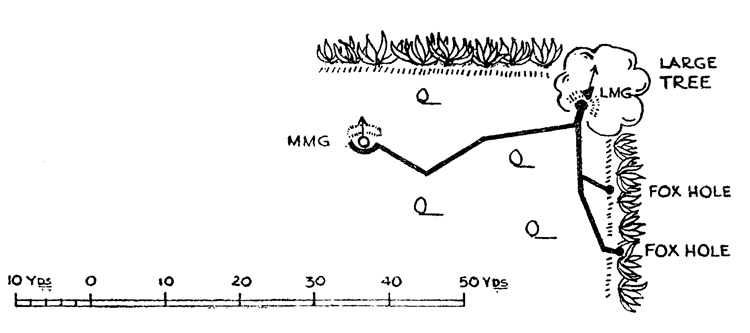

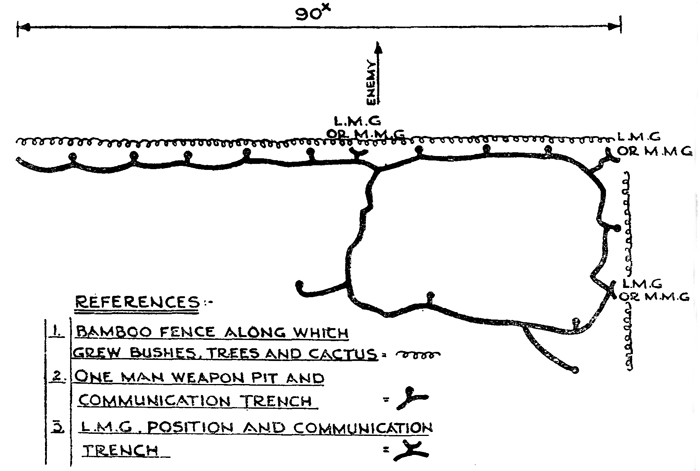

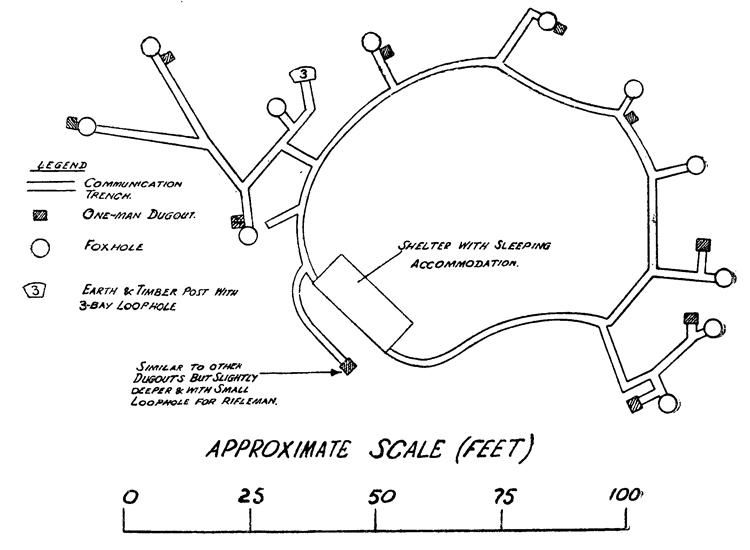

14. The average one man weapon pit or " fox-hole " is 2 to 2£ feet in diameter at the top and from 4 ft. to 4 ft. 6 ins. deep. Dependent on the degree of cover from view in the area where it is sited, it may have a parapet 9 ins. high.

15. Communication trenches are narrow (about 1 ft. 10 ins. wide) and vary considerably in depth. In the position depicted in Example 4 they were 3 ft. 6 ins. deep and a parapet 1 ft. high gave additional protection. Both the trench and the parapet were completely covered over with branches. Tn flat open plains excavated earth is dumped behind the position and no parapets are used.

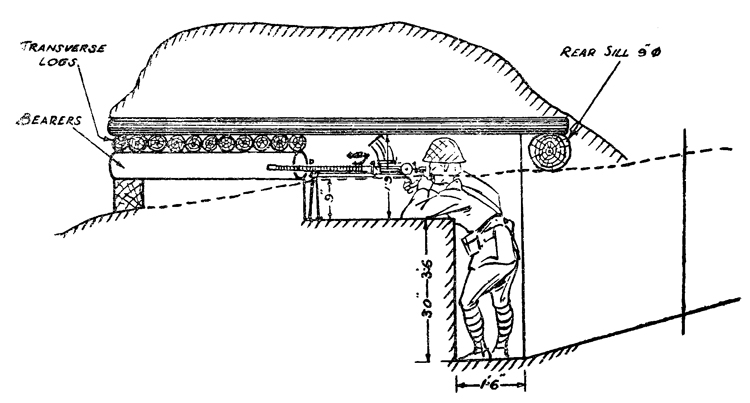

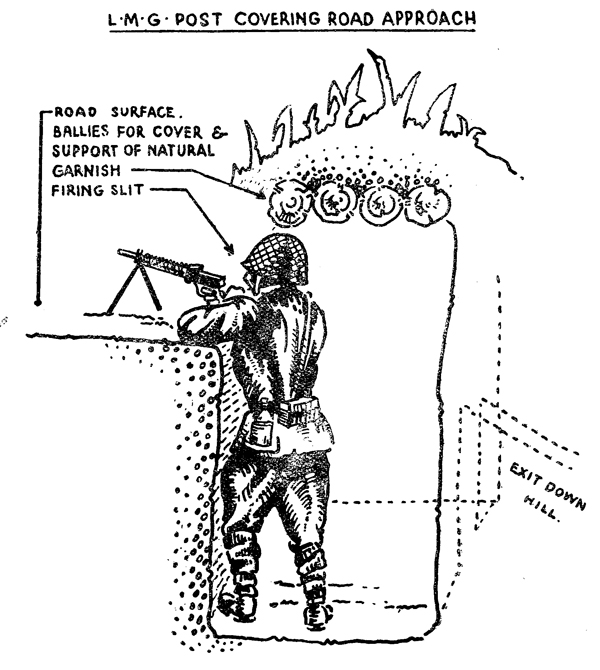

16. There are two types of M. G. positions. The first. which has space for a tripod, is probably for a M. M. G. and the second for a L.M.G-The frequency with which the M. M. G. type is dug suggests :—

(i) that it is preferred because both the L. M. G. (using the bipod if necessary) and the M. M. G. can be fired from it.

(ii) that there is a light tripod in use for the L. M. G. On the evidence available.. (ii) is improbable.

Example 1.

Site.—Corner of a village under trees and behind a cactus hedge. The M. M. G position was sited to cover a bridge, but the cactus hedge had been left undisturbed,, with the apparent intention of shooting the necessary gap in it only when necessary.

Example 2.

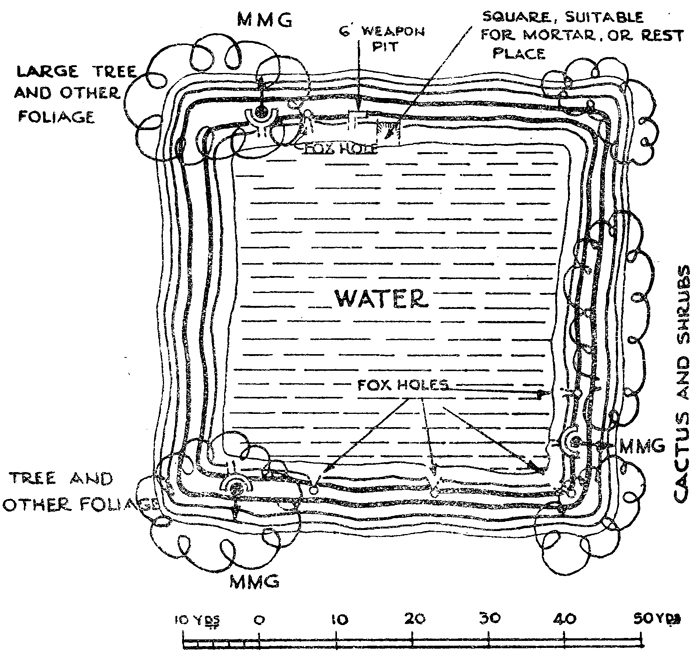

Site.—-An ordinary water tank suoh as those found in Eastern India and Burma. 'Such tanks provide all round defence, water for the garrison, a ready made " communication trench " around the water's edge, and they are often rich in natural cover. The banks, being higher than the surrounding country, afford a good field of fire, and nor the same reason heavy rain has less effect upon them than upon the fields which surround them. They are inclined to stand out in the landscape, but the Japanese are prepared to accept this disadvantage.

The tank illustrated below was on the right rear of the position depicted in Example 7.

Example 3.

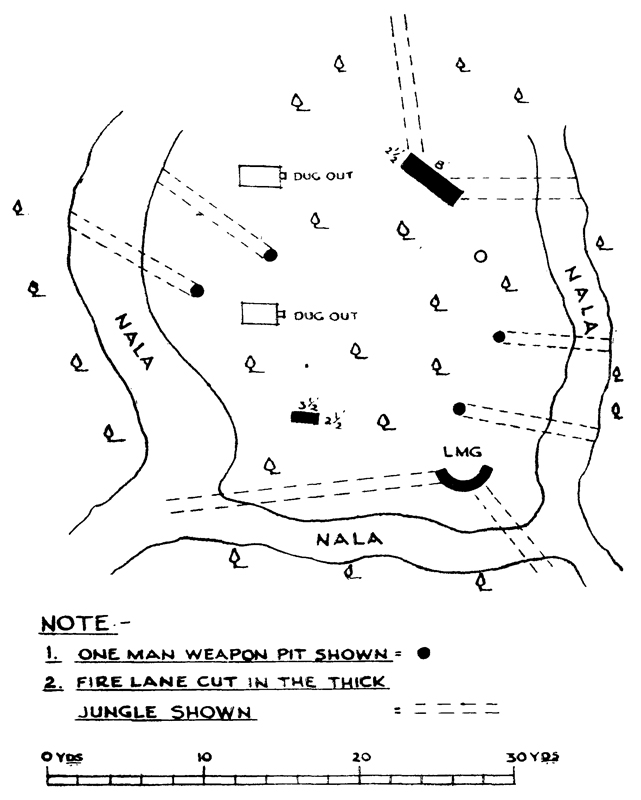

Site.—This is a small post sited in dense jungle forward of the line of foremost: defended localities. Its function appears to be that of a " hide " from which the garrison can either patrol at night or ambush our own patrols. Note that it has been sited on a nala junction. In such thick country movement along nalas is generally the only alternative to cutting a path, and therefore the chances of ambushing a patrol? are good. Fire lanes were cut as far as the nala and a carefully camouflaged sniper's-post had been constructed in a large tree which covered the arear. A Dogra unit captured the position before the garrison had an opportunity to become active.

Example 4.

Site.—This is a common type of defended locality sited on a small hill. An - alternative (fox hole) type of hill defence is shown in Example 5. This locality was just north of the road on the extreme right flank of the position depicted in Example 7. Unlike all other localities in the area, this was wired with barbed and telegraph wire fixed to bamboo uprights 4 feet high. The trenches are depicted below as if they were clearly visible but in actual fact they were either completely covered over with branches or camouflaged by laying carefully cut turf on the parapet. The hill aide was oovered partly with grass and partly with shrubs.

Example 5.

This is an interesting example of a defended locality consisting almost entirely of unlinked weapon pits. It is possible that at least some of those on the hill have been linked by tunnels and that shelter from the shelling and aerial bombardment to which this position was frequently subjected, has been provided by burrowing deep into the hill side. This sketch was made from an aerial photograph and therefore only shows positions visible from the air, but it can safely be assumed that the line of weapon pits was continued under the trees on the south edge of the locality. It should be noted that in this drawing a black dot has been used to indicate both foxholes and M. G. positions.

This locality will be recognized as part of the battalion position given in Example 12.

Example 6.

Site.—This locality was dug on the forward edge of a village and is part of the position illustrated in Example 7. It was sited behind a bamboo fence along which grew trees, shrubs and cactus. It was well camouflaged and bushes and cactus were, as far as possible, left untouched. In front the field of fire was unlimited; behind, village buildings and trees obscured the view. This position contained no features of special interest.

Example 7.

Site.—In the Arakan two miles East of Maungdaw. This position was sited on the forward edge of a village. All localities, except No. 1 and those dug on tanks, were dug behind the bamboo fence of the village ; along this fence grew cactus and numerous bushes and trees, which completely concealed the earthworks. Where overheaded cover was thin branches were thrown across the trenches. The M. M. G. sign used on the sketch below indicates M. G. positions, but it is not known which were L.M, Gs. and which M. M. Gs., also some of the positions shown (for examples 14 and 16) may have been alternative and thus unoccupied. Localities 1, 2, and 9 are shown in detail as Examples 4, 2, and 6 respectively. North and South of the river line the country is generally very open and 300 yds. is the minimum field of fire. Locality 14 consisted of unlinked fox-holes surrounding a small group of houses ; all other localities contained communication trenches.

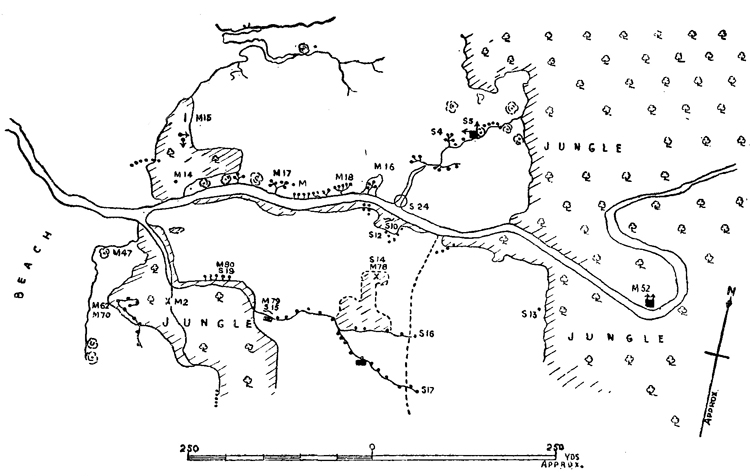

Example 8.

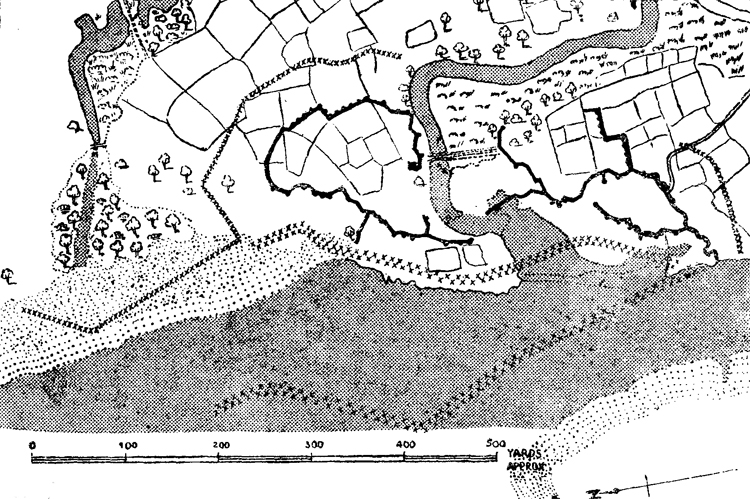

Site.—A beach in Burma. The diagram below shows in detail a typical beaefe defence position which the Japanese have constructed, and are still constructing in Burma. It is a trench system within wire defences.

The trench system consists of two groups enclosing irregular areas and' separated by a tidal creek. The trenches are approximately 5 feet wide at the top, and have-firing bays projecting outwards from them, thus affording an all-round field of fire. The trenches zig-zag irregularly, and the fire bays are spaced at interval's varying between 23 and 70 feet. There are about 66 bays, equally divided between the two groups.

The only defensive structure within the trench system is a pill box, about 10 feet square, within the northern of the two areas. Between this pill box and the river a large tree had been felled to obtain a clear line of sight.

A single line of wire, set on posts at approximately 10 feet intervals, enclosed the two trench systems on the north and south. On the landward side the tidal creek i& used as a boundary to the locality without wire defences along it.

Along the foreshore wire has been laid in double lines, 10 feet apart and in shallow zig-zags, joining at the north and south to the single lines of wire described in the preceding paragraph. A single line of wire in shallow zig zags continues the foreshore-defences northwards along a sandy beach for about 300 yards. The overall width of the defences enclosed by wire is about 600 yards ; its depth about 250 yard's.

A forward double line of wire runs northwards through shallow tidal water from the southern end of the double line on the foreshore for about 550 yards to a point 200 yards forward of the position.

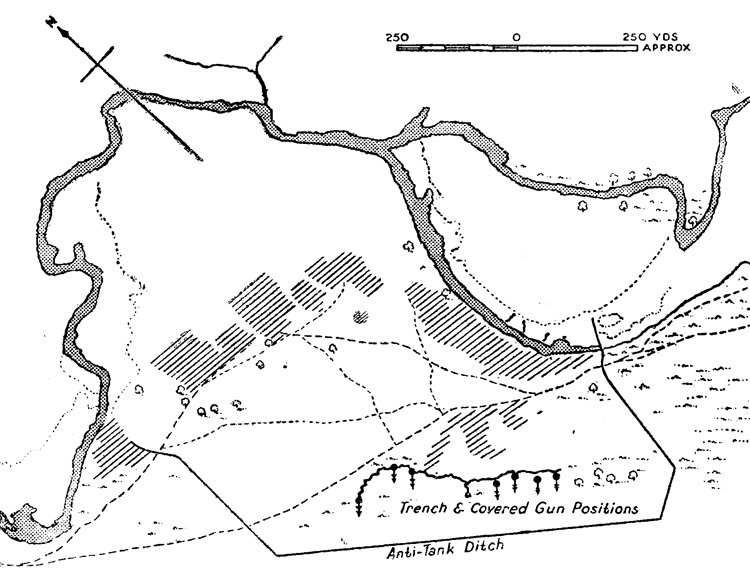

Example 9.

Site.—Burma. The sketch below provides an interesting example of an all sound anti-tank obstacle, partly natural and partly made by digging a ditch. This drawing was made from an aerial photograph and it would appear that the position is still a long way from completion. In this case the preparation of a tank ditch ihas taken precedence over the digging of fire positions. The ditch is about 20 feet wide and about 7 ft. .deep ; spoil has been thrown out on both sides, making a small parapet. The ditdh is full of water.

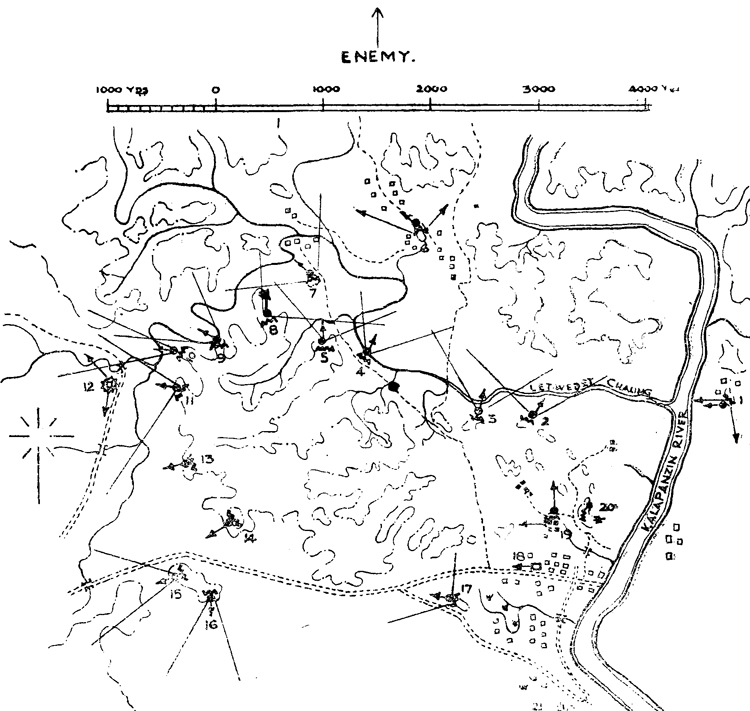

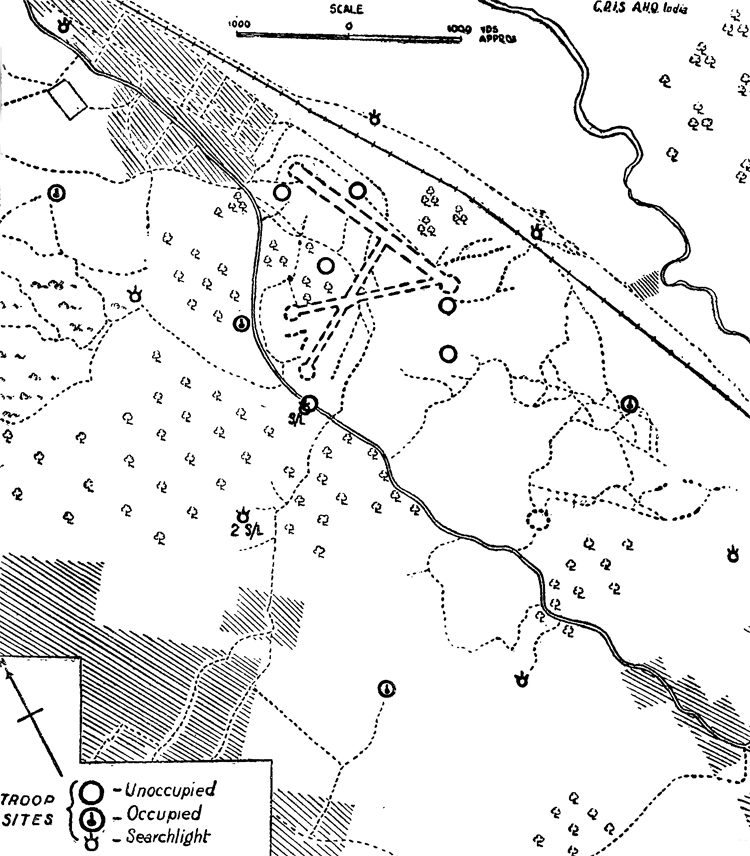

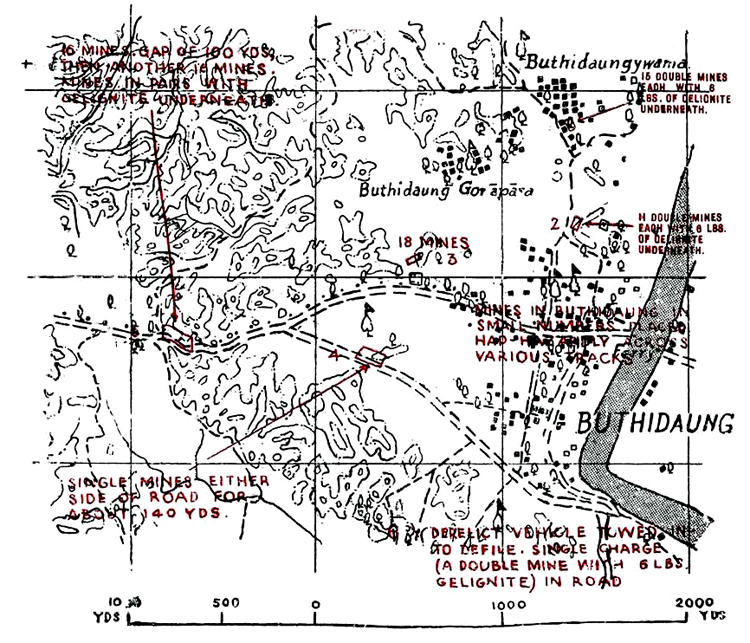

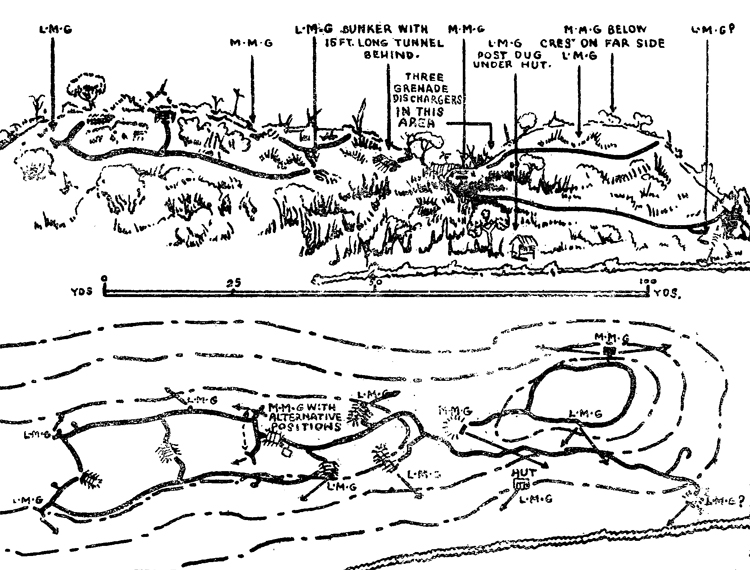

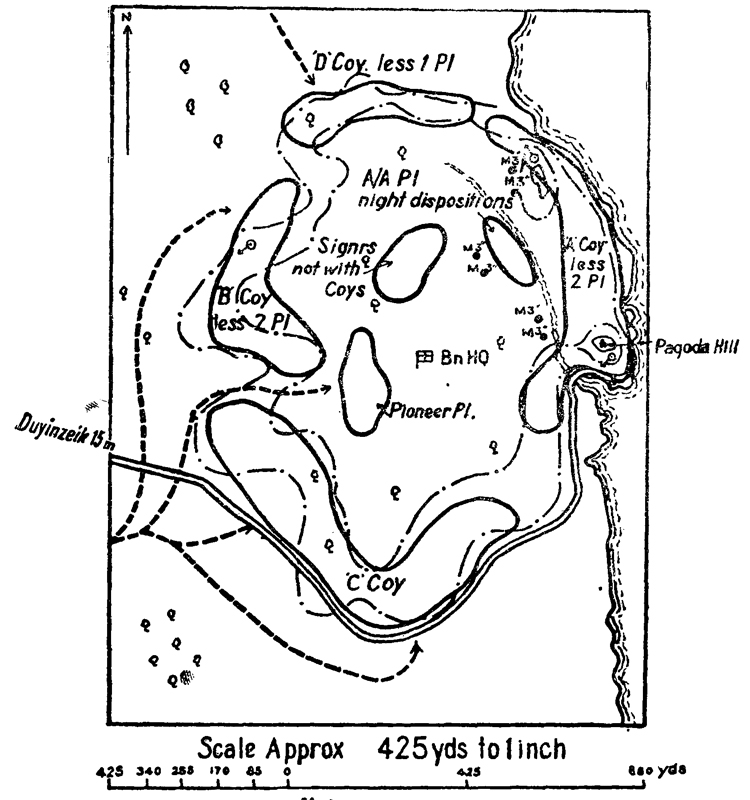

Example 10.

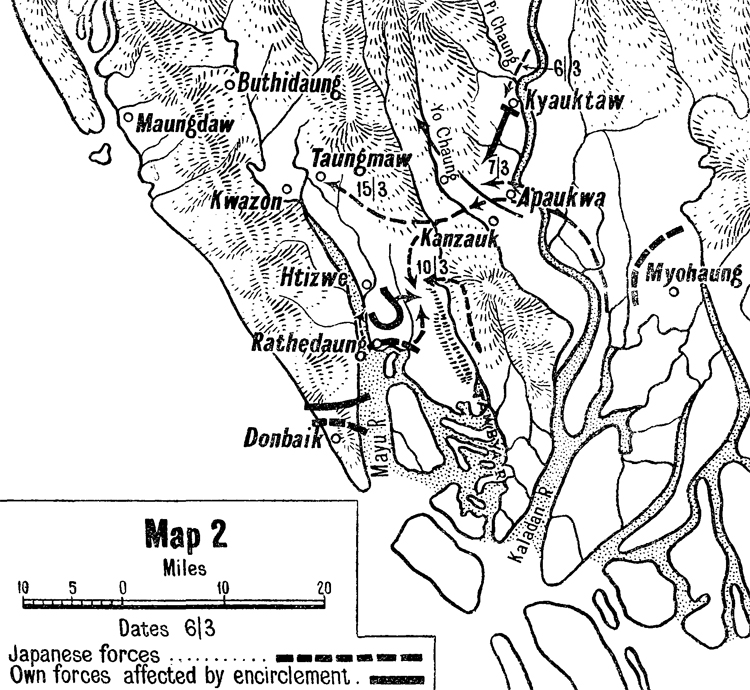

Site.—This position was dug in and around Buthedaung in the Arakan. A point of interest is the siting of localities outside the main line of F. D. Ls.; their apparent function was to hold the lines of approach as long as they could. One flank is resting on a good river obstacle and the Letwedet Chaung is being used as an obstacle for the front.

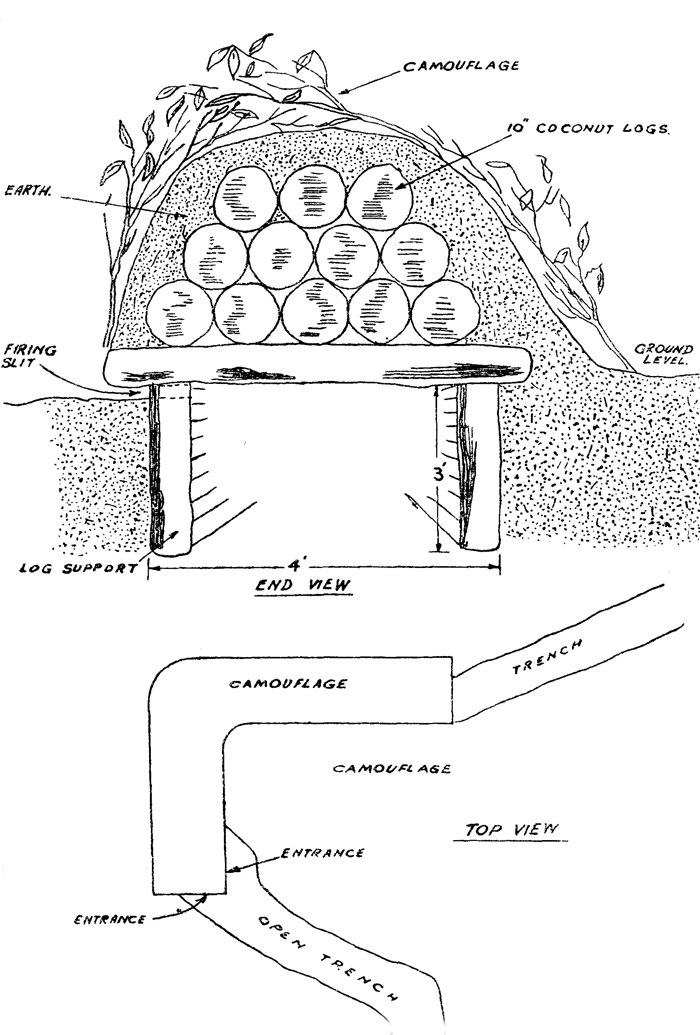

It is not possible to say which positions contained M. M. Gs. and which L. M. Gs., nor is it possible to estimate how many machine guns were in each locality. It is however worthy of note that out of the eighteen localities shown on the sketch as containing M. Gs., eleven contained well concealed M. G. nests, each for two M. Gs. (i.e., Localities 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14, 15, 16). These nests were protected by a 3 feet thick timber, corrugated iron and earth roof ; inside they were six feet long, five feet broad and five feet high. On one of the 6 feet sides were two M. G. platforms revetted with bamboo, in front of each platform was a loop hole 1 foot wide giving two guns together an arc of fire of not more than 60°.

Localities 8, 9, 10 and 11 were linked by paths to form one position. The paths were cut on the rear slopes of the hills and tunnelled through the jungle so as to be invisible from the air. Localities 14, 15 and 16 were linked in the same way.

Locality 6 was sited on a hill covering an important approach to the position. It contained a M. G. nest, four open M. G. positions, and eight fox holes.

Locality 12 was constructed on a tank, as depicted in Example 2.

One man weapon pits unconnected by communication trenches predominated -i» this position.

Localities were mutually supporting.

Battalion Position at Buthedaung.

Example 11.

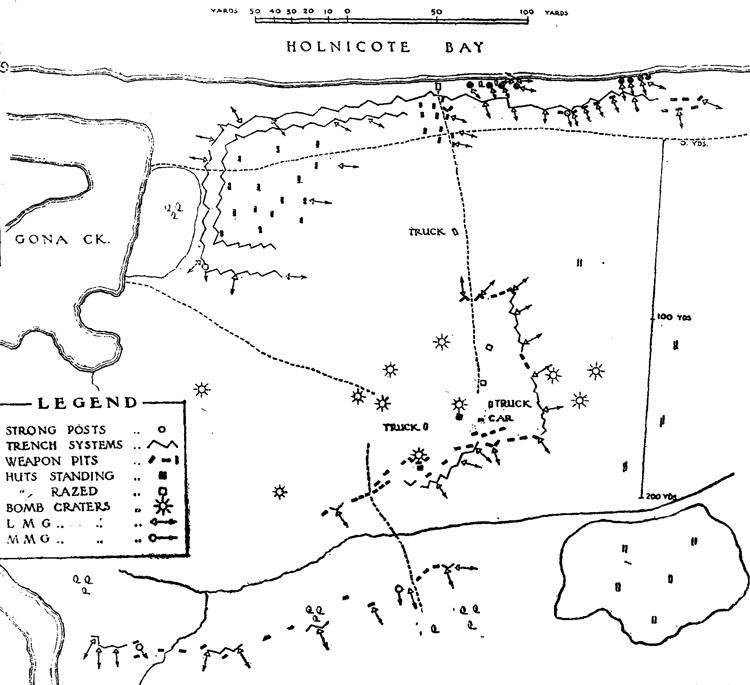

Site.—This illustrates enemy defences in Gona. Unfortunately there is little to indicate the strength of the force engaged, but the number of light machine guns (57) suggest the fire power of approximately six rifle/L. M. G. companies at full strength. The most southerly line suggests a company with two M. M. Gs., attached ; in marked contrast to company frontages in Burma it occupies a frontage of exactly 200 yards. It should be noticed that the right flank of this company rests on a creek and its left flank is fairly close to what appears to be a small marsh.

Sketch map enemy Defence Gona.

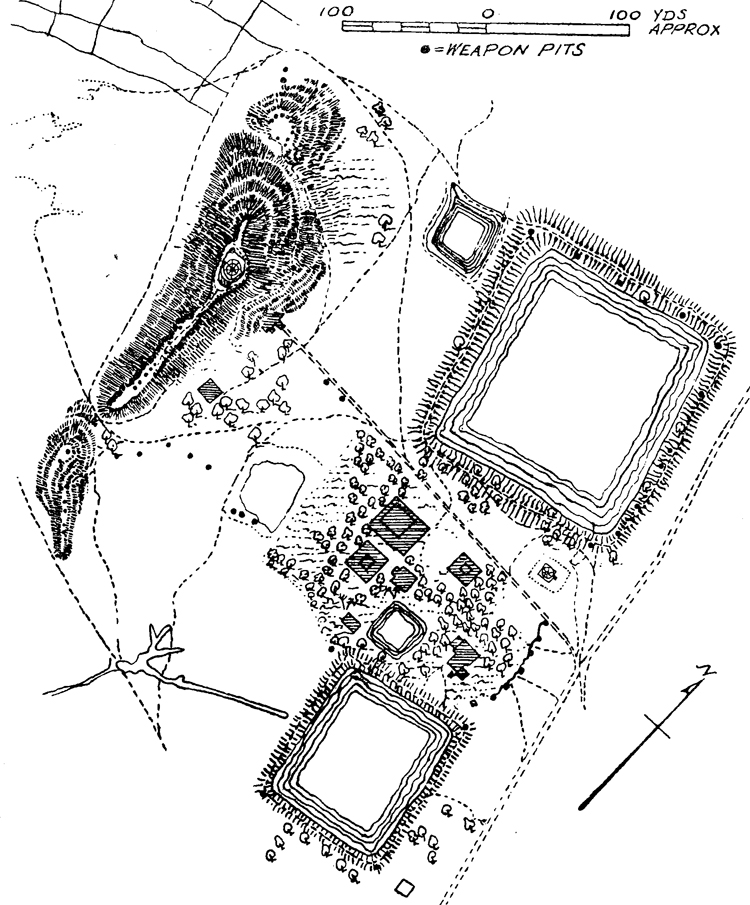

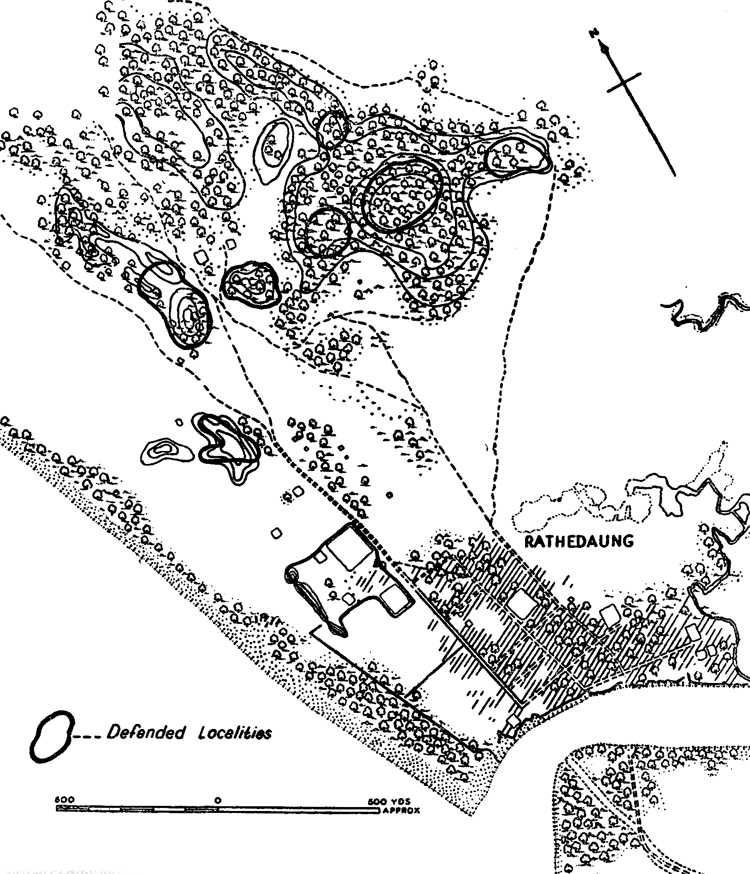

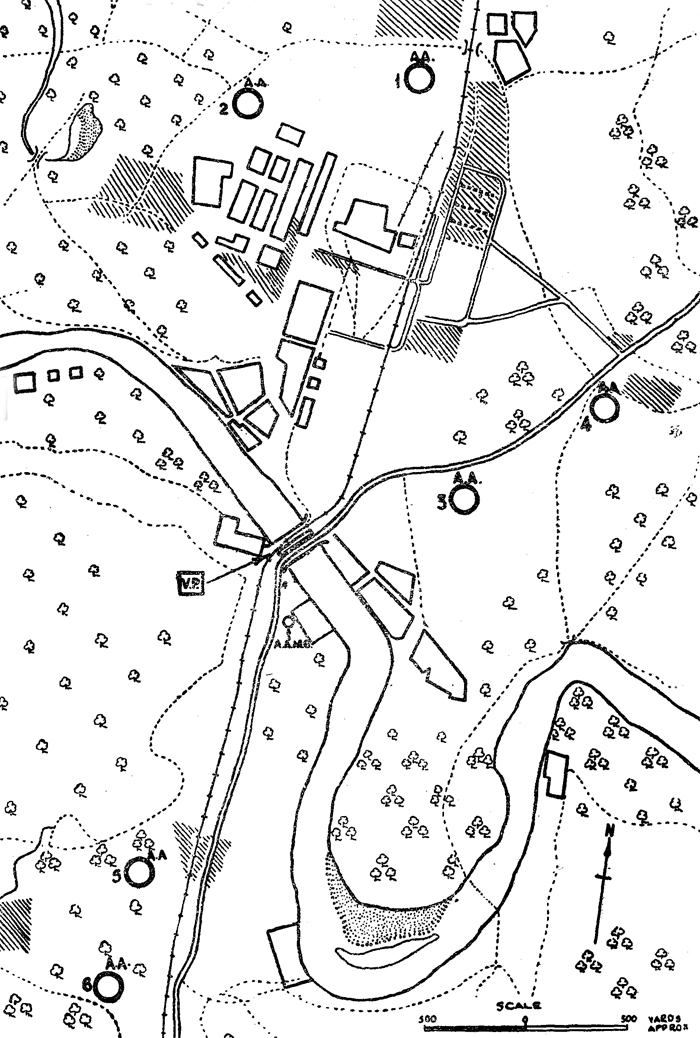

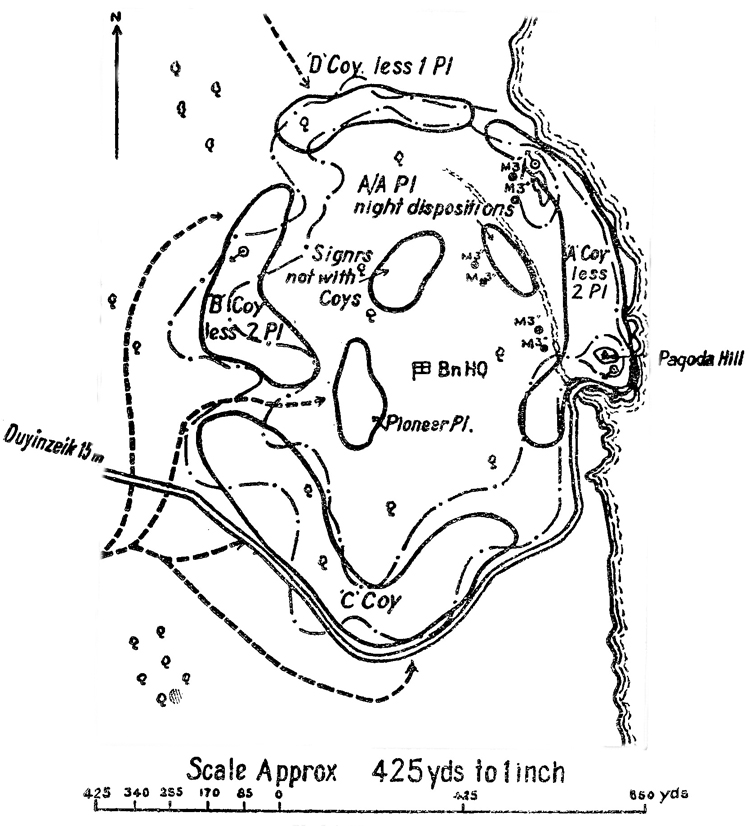

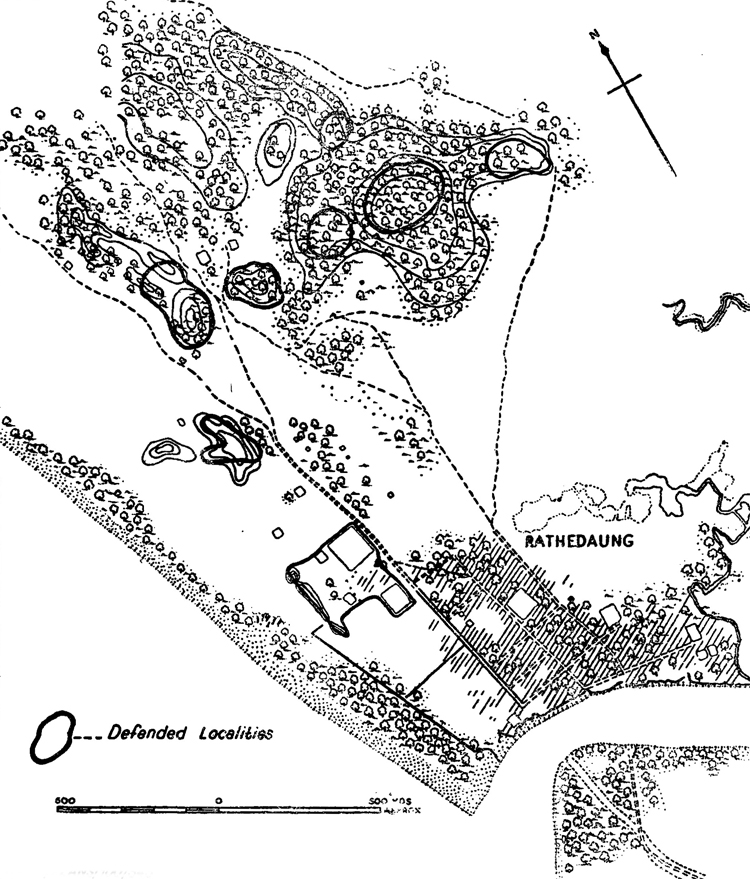

Example 12.

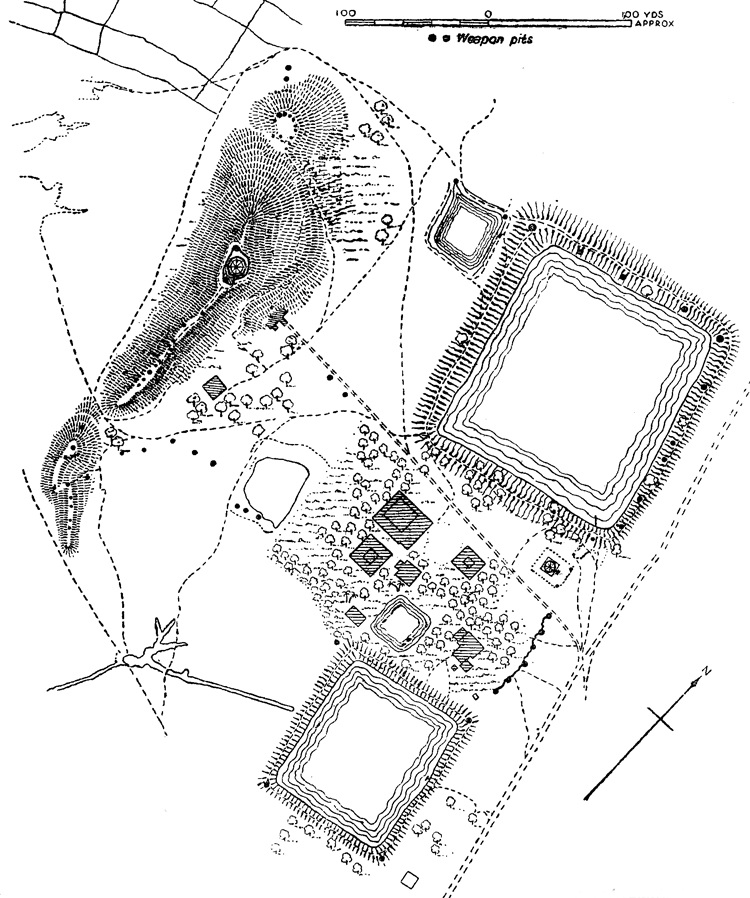

Site.—Rathedaung. Except in the case of the locality illustrated in Example 5 it is only possible to show this position generally. It is reproduced here because even without detail it gives some indication of the frontage and depth occupied by a battalion holding a defensive position amongst small thickly wooded hills. This position was held by the Japanese for some weeks and narrow flanking movements against it failed.

Forward localities were sited on the highest ground in the sector and organized for all round defence. Trenches in the most northerly localities were continuous.

Our own positions were North of those shown in the sketch map.

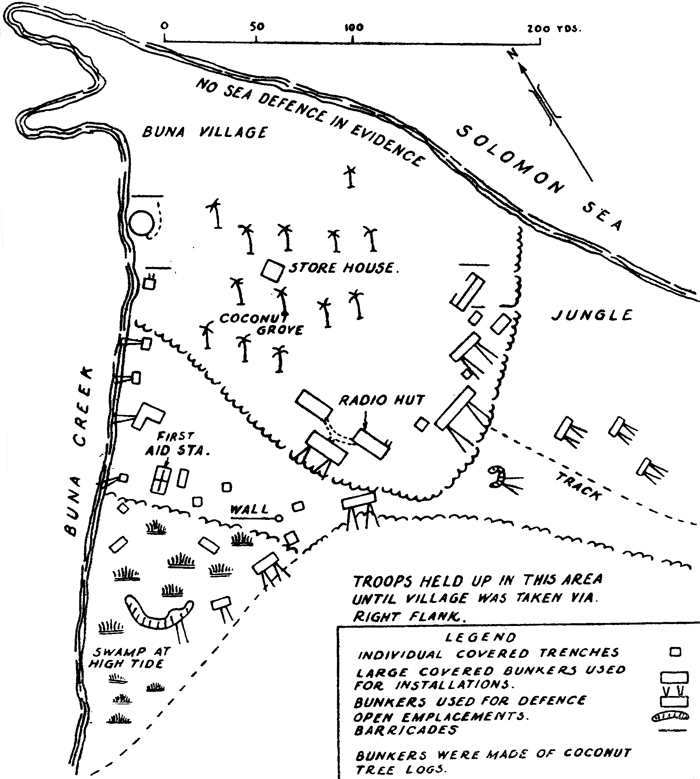

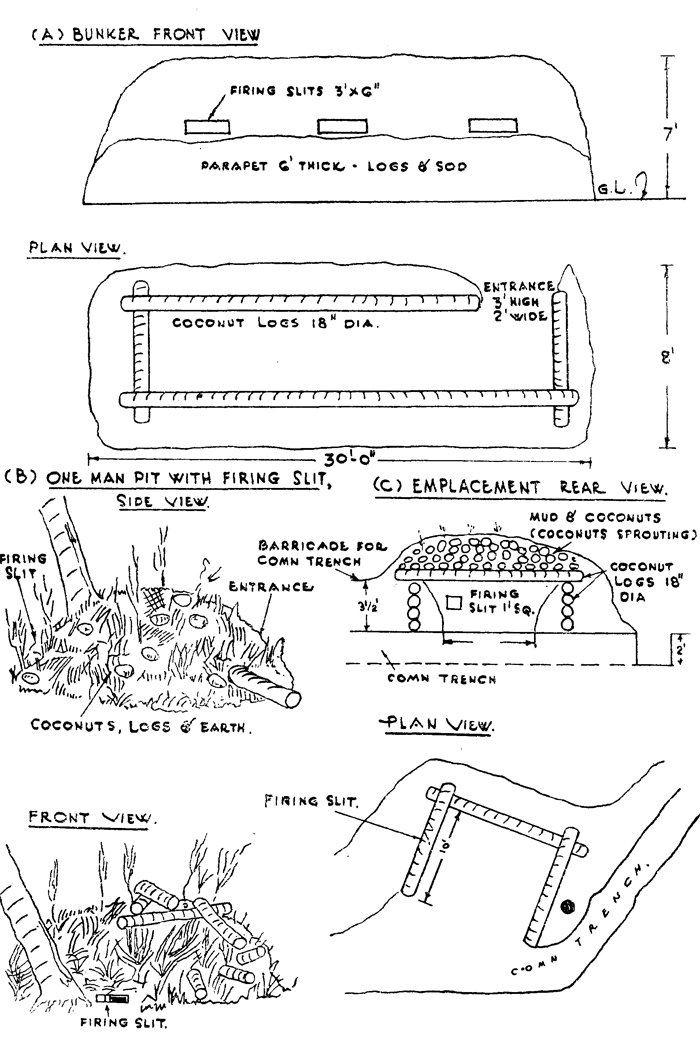

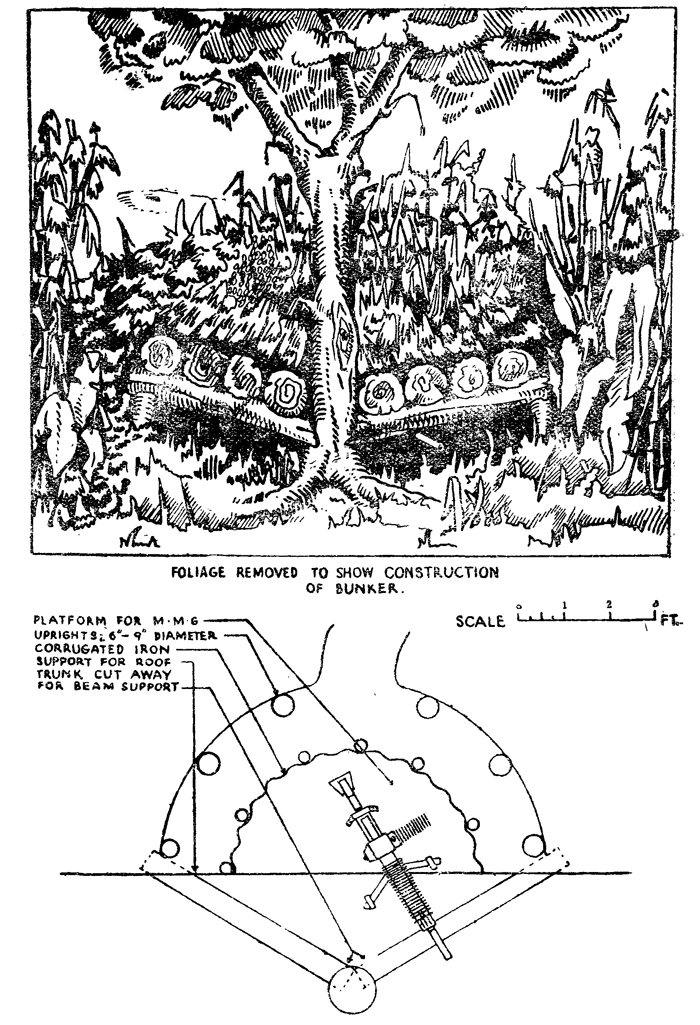

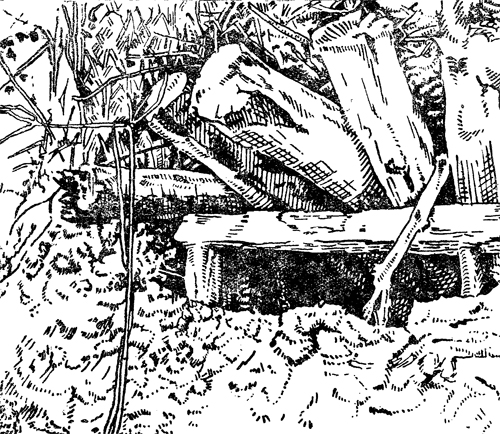

Example 13.

Site.—Buna village. This is another example of Japanese defence in the South West Pacific. Again flanks rest on natural obstacles, and the advanced posts 30 to 80 yards outside the main position should be noted. The defences in this position •consisted almost entirely of " bunkers ", the detailed construction of which is shown in Examples 14 and 15.

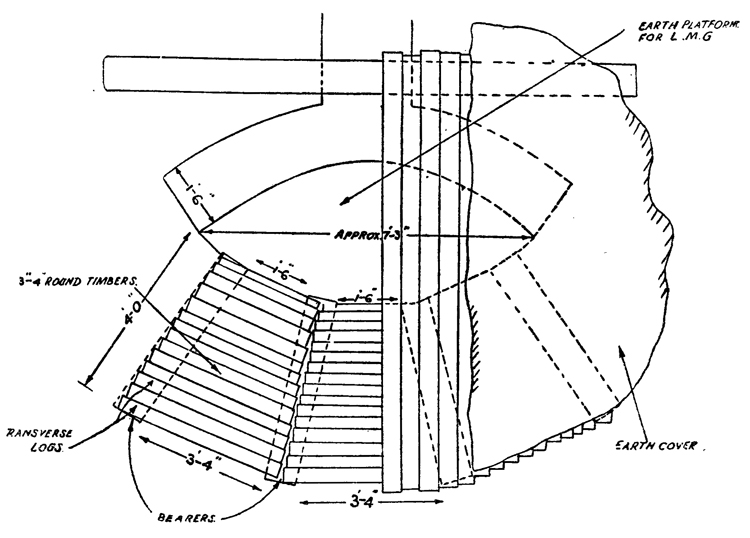

Example 14.

Strong points.—Strong points, as seen in Burma, fall into two types, both of which are illustrated below.

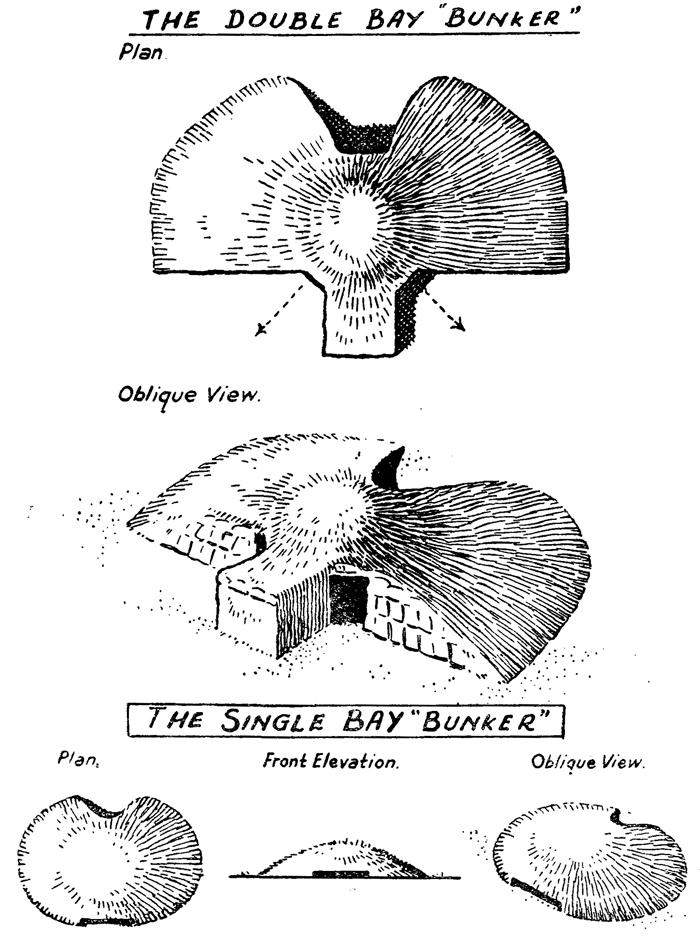

The Double Bay " Bunker ".—These are built in two sizes, 25 ft. by 15 ft. and 60 ft. by 40 ft. They consist of mounds of earth from 5 ft. to 12 ft. in height, with a rear entrance well recessed into the mound. Forward, a central, apparently solidr block projects to form two bays. These bays vary in size.

The smaller sized earthworks form part of the main trench system, with which they are linked, but the large " bunkers " appear to be isolated.

The single Bay " Bunker ".—This consists of a ronghly circular mound of earth about 25 ft. in diameter and 5 ft. high, with entrance at the rear opening on to a craw! trench or the main trench system. In front is a firing-slit on, or slightly above ground level, from 6 to 8 ft. long and about 1 ft. 6 in. to 2 ft. high. Inside there is presumably a timbered diig-out partly below ground level.

A typical beach defence position is illustrated in Example 8. It is in positions of this type that the " bunker " strong points have been seen.

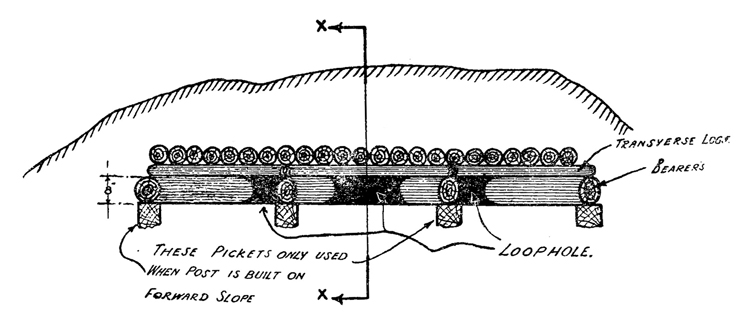

Example 15.

Earthworks in the South West Pacific Area.

DETAILS OF BUNKERS-JAP DEFENCES—CAPE ENDAIADERE DEC. 42.

All dugouts and bunkers have had firing slits so small as to be invisible from the-front, and with heavy overhead cover made it impossible to reduce th.em with a frontal assault with infantry. It is therefore necessary either to secure a direct hit with artillery or to overrun or envelop them and attack from the rear.

JAPANESE SHELTERS & BUNKERS—CAPE ENDAIADERE AREA.

CONSTRUCTION DETAILS JAP EMPLACEMENTS—CAPE ENDAIADERE

DEC. 42.

The angular plan of some of the dugouts made it impossible to eliminate all enemy resistance from one dugout by throwing in a grenade. There have been instances where this was apparently assumed, with the result that men who have actually got. nto the entrenchments, have been shot from behind.

5. Conduct of the defence.

17. Surprise is achieved by silence and concealment. Until attacked, troops occupying forward localities very seldom open fire even if the target offered is a good one, consequently it is rarely possible to pin-point their machine gun positions.

From a hill four or five hundred feet above an enemy company locality sited in ;an open plain, there is surprisingly little to be seen : no wire, nothing resembling trenches, and no movement. Here and there a few feet of obvious camouflage, perhaps a single hole showing in the bank of a nala, and that is all. On the defensive in the Arakan the enemy rarely initiated any movement himself during the hours of daylight. The complete still suggested that he slept during the day in order to reserve his energies for the night, when his patrols were invariably active.

18. Machine Guns.—Following normal practise the Japanese make the machine

gun the principle weapon of defence. Automatic weapons are sited to fire along prepared lines, lanes being cut in the jungle if necessary. Medium machine guns are

sited well forward and are generally sub-allotted to platoon localities, they are often

to be found on high features or dug into the banks of tanks, they are also sited to cover

the main lines of approach. They are often sited singly and are invariably provided

with alternative positions. An important point to remember is that during the defensive battle M. M. Gs. sometimes fire along a line about ten yards from the forward

edge of Japanese F. D. Ls., and assaulting troops, if unprotected by smoke or darkness, may therefore suffer heavy casualties just in front of the enemy position, particularly if they have got bunched in converging on to the objective.

19. Mortars and Grenade Dischargers.—In the defence, mortars and grenade dischargers come next in importance to the machine gun. Mortars of 3 inch or larger calibre may be allotted to rifle companies at the scale of one per company, but the weapon most frequently used by forward units is the 2 inch grenade discharger of which there are three in each platoon. This is a rifled weapon which throws a small shell 700 yards. Once an attack is launched mortar and grenade discharger shelling is frequently directed on areas which cannot be reached by flat trajectory weapons. Particular attention is paid to probable lines of approach and likely forming up places.

20. Snipers.—The extent to which snipers are employed varies greatly with each front. The minimum effort is made by one or two snipers covering paths between our own localities, and the maximum effort, which was experienced in the South West Pacific Area, is a large number of snipers left behind by troops who advance and then fall back. Although sniping varies a great deal in intensity there are certain places where snipers posts may be expected—

(i) above small advanced positions, (ii) on the flanks of localities,(iii) covering lines of approach to the Japanese positions, (iv) covering paths in our own area, (v) covering gaps made in our telephone cables (this has been reported once).

21. Patrols vary in strength from one N. C. O. and three men to an officer with eighteen or more other ranks. They are active every night and their tasks vary from drawing fire in order to discover our positions, to determined raids in which the assault often comes in from a direction opposite to that in which crackers, red tracer and auto matics have been fired. In one instance in Burma this year a patrol crept up to a section post without being seen or heard, they then rushed the post the garrison of which was taken completely by surprise and overwhelmed. Finally as an example of patrol activity at night the practise of infiltrating between localities held by troops new to a sector, must be mentioned : the object in this case is to get localities in a difficult sector (for example in close hilly country) to engage each other. In this they have occasionally been successful.

In the South West Pacific daylight patrols of six to ten men have also been met, while a document recently captured in Burma detailed a party consisting of a cadet, a serjeant, and five soldiers (including one nursing orderly) for a patrol which was to carry provisions for four days.

22. Artillery.—Up to the time of going to press little use has been made of artillery in the defence. Where it has been employed against us, its activities have been confined mainly to counter battery work and it is interesting to note that artillery has not been employed against attacking troops. In future operations, however, artillery must be expected. The 37 mm. anti-tank gun has been in action against our tanks. This was sited in a foremost defended area, and carefully concealed in a nala.

23. Battle.—From the Japanese point of view, the defensive battle begins only

when the assaulting troops are too close to be missed by their light and medium

-machine guns. Carefully concealed M. G. positions then come to life, and now, when

the assaulting troops are too close to the objective to receive additional.support from

artillery, M. M. Gs. and mortars, they are, if unprotected by smoke or darkness,

met by accurate and heavy concentrations of machine gun fire. If they are assaulting

up a hill to this is added showers of grenades, and any L. M. G. detachments who stop

to lie down and fire at short range from exposed positions are engaged by grenade

discharger shell and light machine gun fire.

The Japanese tunnel into hill sides and build dugouts which afford adequate protection against all but a direct hit from a field gun. Well built earthworks often render his destruction by the normal supporting weapons impossible. Supporting fire shakes him and makes him keep his head down, but if the assault does not go in with all possible speed after the supporting fire has lifted he is quick to seize the momentary advantage which slow troops may give him, with the result outlined above.

24. Counter-attacks.—The Japanese launch immediate counter-attacks against troops who have captured part of a locality. These small local counter-attacks may be made by only a dozen men led by an officer ; they are preceded by a shower of grenade discharger shells and the charge is made with automatic weapons. This immediate counter-attack may be launched five to ten minutes after the locality has been penetrated. A wild war cry, to which is sometimes added the shout " Charge !" m English, gives warning of what is impending.

6. Examples of the defensive battle.

Example 1.

The Japanese sited a foremost defended locality on the hill illustrated below. All earthworks were carefully camouflaged and had it not been for sentries in our own foremost positions, about fifty yards down the left slope of the hill, hearing the Japanese talk at night, it would not have been possible to say definitely that they were there.

Reconnaissance parties, exposing themselves boldly on a ridge facing this position and 400 yards from it, were never fired upon, and many rounds of 3 inch mortar bombs were fired into it without producing any reaction.

The general line A-B was nearest to the point of observation, the position, however, continued on the right of A following the high ground which curved back slightly.. It also receded behind B following the highest contour.

The post around A-B was probably held by a platoon as part of a company holding the main hill of which this feature was only a part.

The information then, available to the attacking troops, was that there were some enemy on the hill who had never been seen. They had been heard to talk at night and they were believed to consist at the very outside, of one platoon.

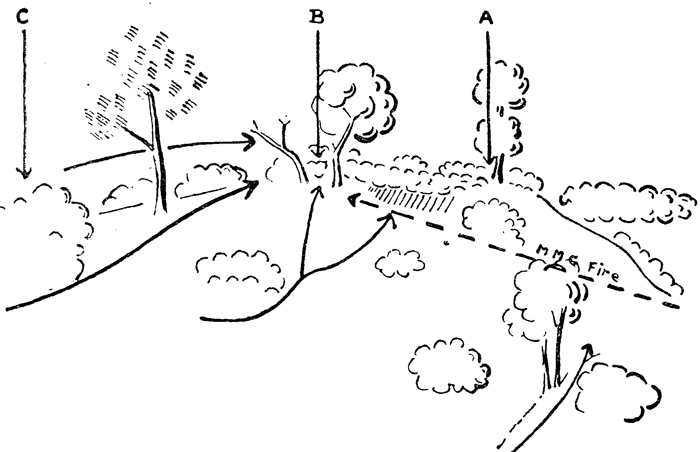

After an intensive mortar bombardment one company launched an attack up< both sides of the spur from C. The black arrows indicate approximately the line of advance of the main assaulting parties.

The leading assaulting troops made good progress until they were about 30 yards1 from the general line A-B ; then a veritable hurricane of fire was let loose upon them. They were engaged by L. M. G. fire and grenade discharger shell and began for the first time to suffer appreciable casualties. Shouting then* war cries they continued to-climb the hill, making use of such meagre cover as the small bushes and folds in the ground offered. As the action grew in intensity camouflage began to slip off the parapet of what could now be identified as a continuous trench, part of which ran along the front A-B. When the foremost troops were about ten yards from the parapet, they were subjected to accurate M. M. G. fire from a gun sited in another locality. Although greatly weakened by casualties they continued to advance and, led by their Company Commander who hurled grenade after grenade into the Japanese position, they finally stormed and occupied the trench, killing or driving out all Japanese in that part of the locality.

About ten minutes later there was a wild howl, as of jackals and hyenas; a shower of grenade discharger shells fell amongst our troops, and with shouts of " Charge ! " the Japanese counter-attacked with automatic weapons, forcing our troops off the hill again.

DISCUSSION.

This company battle serves as a vivid example of Japanese method in the defence. Their positions were well concealed and nothing tempted them to give them away ; thus at zero hour the attackers could be certain neither of the extent of the position nor the strength in which it was held. They had heard Japanese talking in this area at night and with the Japanese predilection for commanding ground they could reasonably be expected to have a defended locality there.

Fire was held till the attackers were thirty yards and less away, and not until they were ten yards from the parapet were they engaged by a medium machine gun in a neighbouring locality. This is a common Japanese method of achieving surprise in the defence.

Finally success which was not reinforced was turned to failure by a small but determined local counter-attack. The immediate counter-attack is a common, but not invariable feature. There have been cases in which captured localities have been made untenable by fire alone.

Example 2.

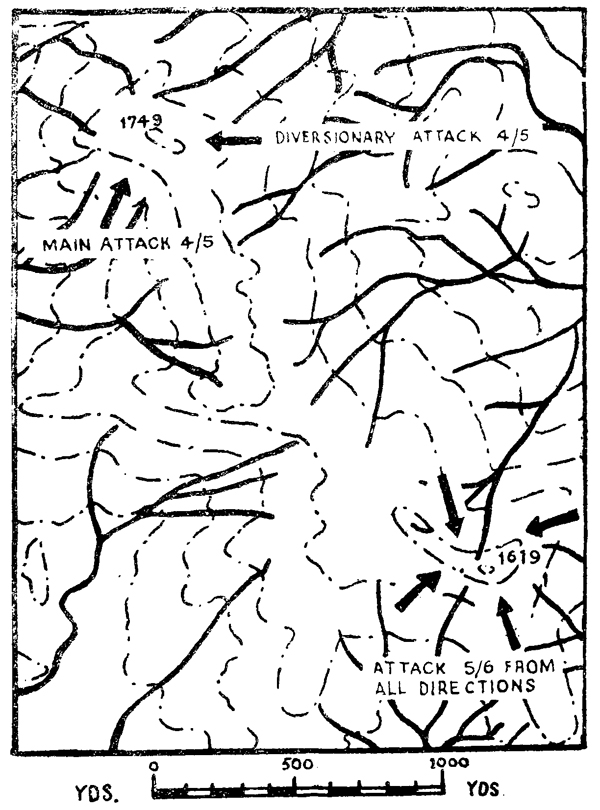

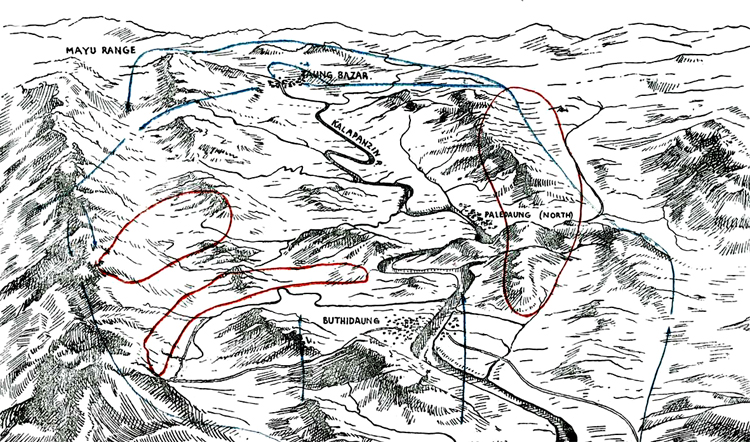

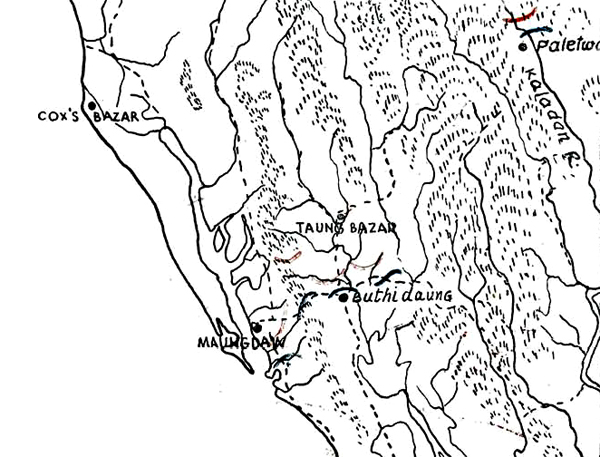

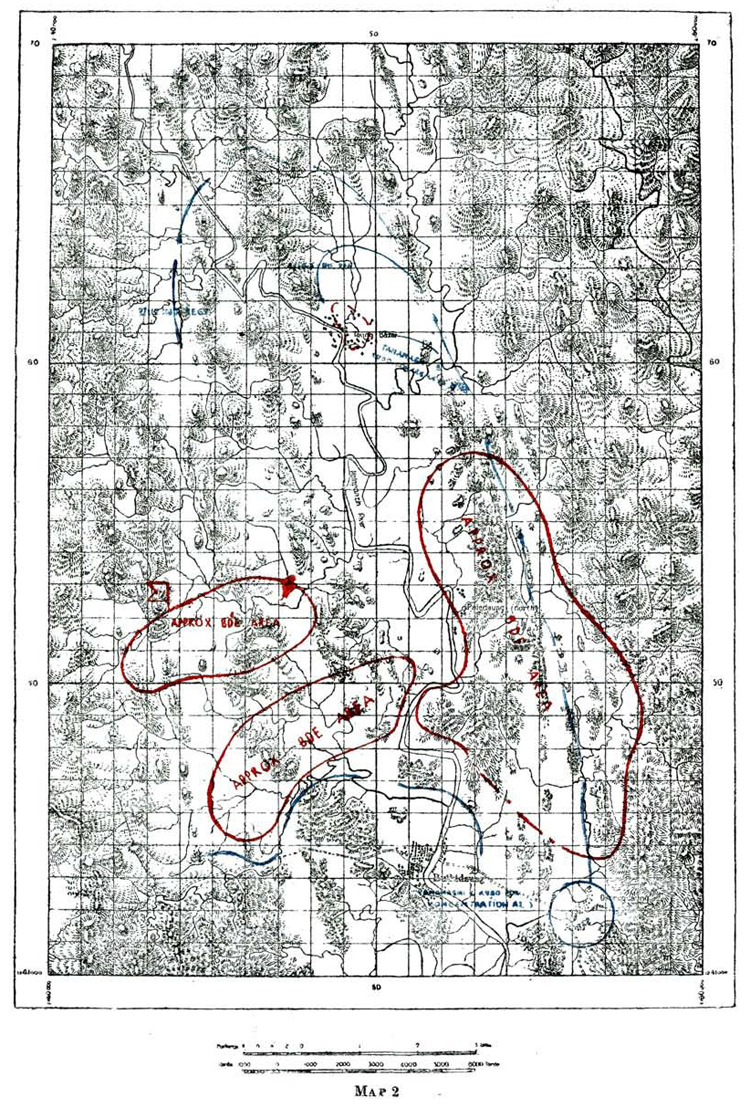

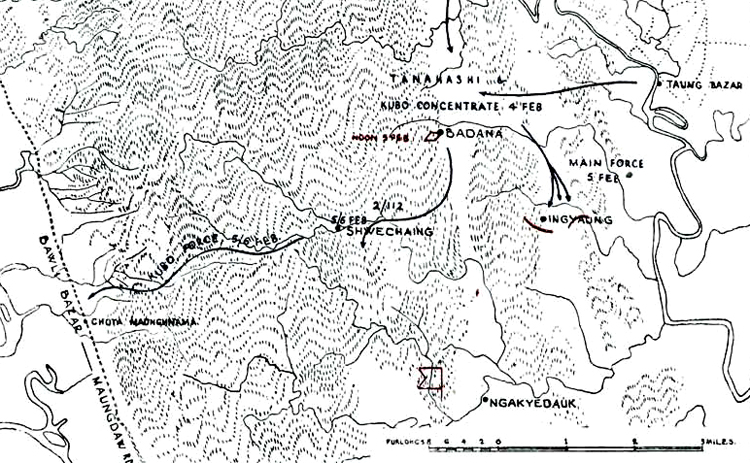

(See sketch maps.)

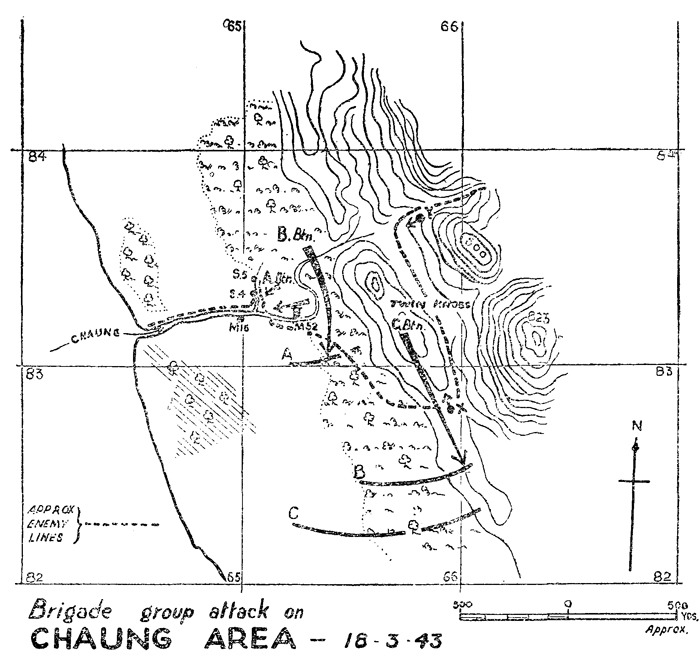

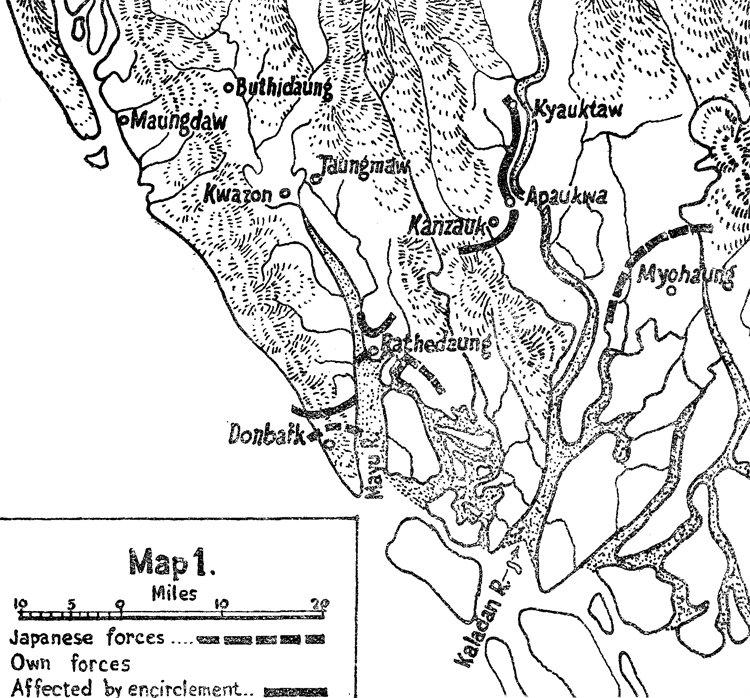

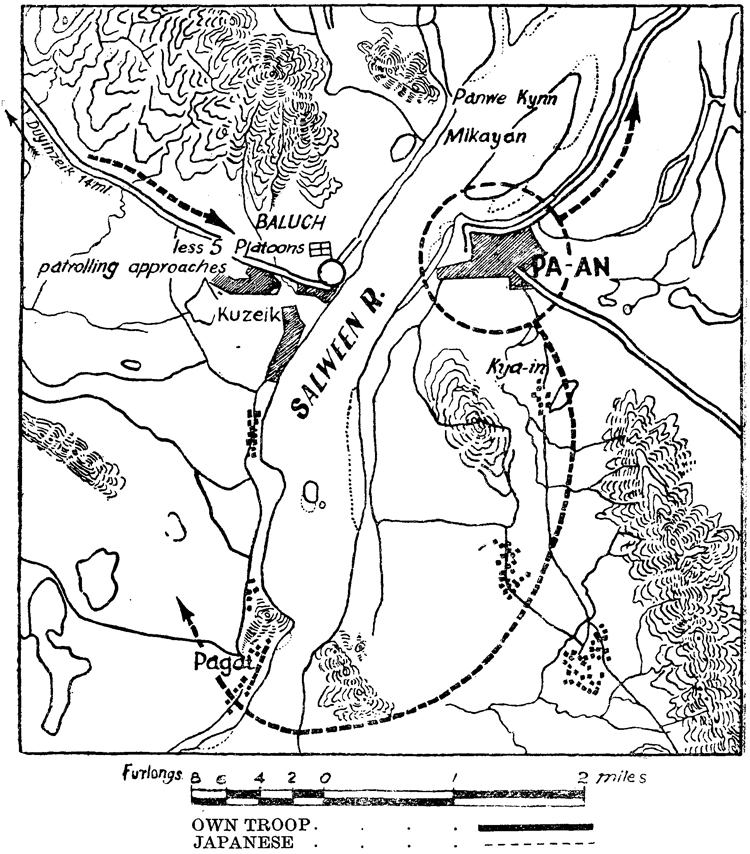

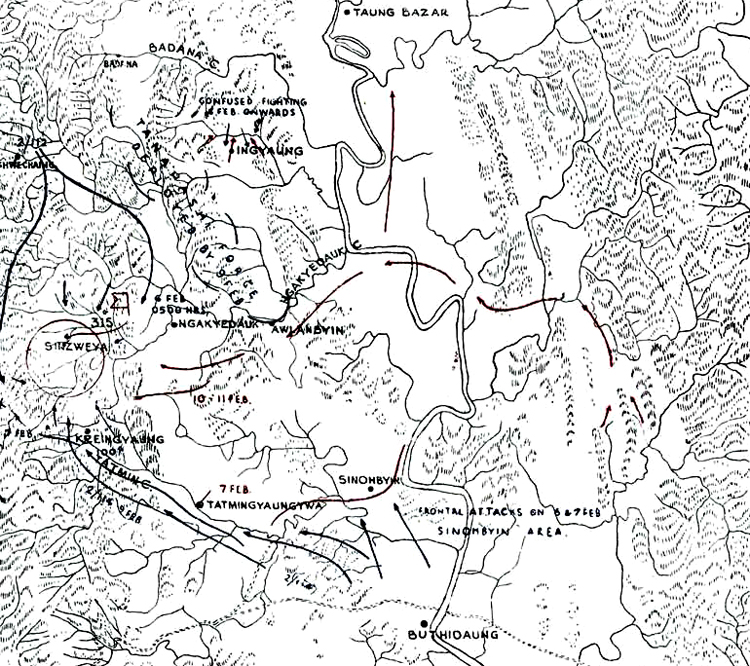

The following brief account of an attack made by a British Brigade in March 1943 against a strong Japanese defensive position in Burma, on the Mayu Peninsular North of Donbaik, serves as a classic example of Japanese defensive tactics.

The plan for the attack was divided into four phases :—

Phase 1. 0545 hours A. Bn. to capture the Eastern half of the Chaung as far West as Ml6.

Phase 2,—0645 hours B. Bn. to capture the jungle area as far as line marked " A ".

Phase 3.—0710 hours C. Bn. to extend their position on Twin Knobs to as far South as the line marked " B ".

Phase 4.—0850 hours B. Bn. to exploit to line marked " C ".

Supporting Arms.—Artillery and M. M. Gs. supported the attack with a barrage and concentrations.

The Japanese position.—(See sketch map below).—The Chaung itself is a strong aatural obstacle, which the Japanese made into an excellent defensive position, by building an intricate system of communicating weapon pits and strong points, and at least one pill-box (S5). All posts were mutually supporting.

The pill-box, which consisted of an outer covered weapon pit, and an inner chamber which is reported to have had both metal and concrete incorporated in its structure, was sufficiently well constructed to withstand no less than three direct hits from a 3 -7" howr. at point-blank range. It follows, therefore, that assaulting troops on and around the pill-box could be subjected to heavy mortar fire without any dstri-mental effects to the occupants.

All other works were dug well down and presumably provided with dug-outs, for although approximately 124 tons of shell were fired into the Chaung area immediately prior to the attack, there was no indication that the enemy's fire power had been-impaired.

The Chaung is overlooked from the East by two commanding features, Hills 823 and 500. These are both steep and densely wooded. Although no weapons were pin-pointed on these features, mortars, M. M. Gs. and at least two 7 *5 cm. mountain guns undoubtedly fired from there. These weapons could thus put dowra defensive fire anywhere in the area, by day, by night, or through smoke.

Unlike other Japanese defensive positions, the posts, weapon pits and fox holes,, in and about the Chaung were clearly visible from the air and in many cases could be-seen from O. Ps. This does not mean that any movement or weapons were visible^ but it was possible to discern where earthworks have been dug. However, in the jungle and on the hills 823 and 500 positions were so well concealed that with the exception of the two strong points which held up B and C battalions they remained undiscovered to the end of the battle.

Course of the Battle.—A. Bn. commenced their advance without appreciable opposition, but soon the company attacking the Chaung from the North experienced the now familiar Japanese tactics of withholding their fire until the last moment, and it was not until they were traversing low loose strands of wire, about 15 yards from S4 and S5 that intense fire was brought to bear on them. These two posts were attacked repeatedly, but without success ; our troops could find no opening through which to throw grenades and whilst on and about these posts they were subjected to> mortar fire to which the posts themselves were immune. The other two companies were more fortunate, and although they were subjected to showers of grenade discharger shells and hand grenades whilst advancing down the Chaung, succeeded int taking their objective, which was up to inclusive M16. A proportion of these troops advanced up the small Chaung and cleared it as far as S4 where they in their turn were held up. As the light improved, and as presumably the Japanese realised the-position, showers of projectiles from all weapons were fired into and around the-Chaung, and M. M. Gs. opened up from the flanks.

Meanwhile Phase 2 began and B. Bn. advanced only to be held up ?; what was> described as a Strong Point similar to S5 (M52 on the Sketch). B. Bn. were unable to reduce this post and were subsequently withdrawn.

Phase 3 commenced according to plan, but C. Bn. almost immediately suffered the same experience as B. Bn, in that they ran into a cunningly concealed M. M. G. Post just beyond the start line. This post was so well hidden, that it escaped notice when the area was reconnoitered prior to the attack. This Post also held out.

DISCUSSION.

The attack failed through no lack of courage ; the dash and daring of the attackers has been aptly described as an epic of collective gallantry. Why then did the defence succeed ? There are important reasons—

Following his normal practice the Japanese held his fire until the assaulting troops were almost upon him; only then did his machine gun nests come to life— machine gun nests about the strength or existence of which we knew little or nothing. To quote from our own defence pamphlet " The main task of medium machine guns will be to take toll of enemy unarmoured troops " and no M. M. G. is better sited to fulfil this role than one in an undetected nest with a big enough covering of earth, timber, and perhaps steel and concrete, to withstand the preliminary bombardment. In fact by continually improving their positions and by careful attention to camouflage the enemy had achieved surprise in the defence.

Strong posts which could withstand the fire of our artillery could also withstand the fire of Japanese mortars which gave additional protection to their garrisons.

The first and chief problem then, which the Japanese defensive position presents, is the problem which has faced every modern army for more than 25 years—it is the detection and neutralization of the machine gun firing from a well built nest.

It will be noticed that no counter attack was launched in this battle, elements which had penetrated being dealt with by intensive mortar and grenade discharger shell fire alone. This practice of bringing down defensive fire on ones own position is likely to be a common feature of Japanese defensive tactics. In fact either by immediate fire or immediate counter attack the Japanese will attempt to make an over-run locality untenable.

7. As others see us—British attacking Japanese defending. (Translation of a captured Japanese document.)

1. They are generally cautious in attacking and in planned attacks they have a

tendency to use positional warfare and make exhaustive reconnaissance preparations.

We should strengthen our position more and more while they are getting ready, and

at the same time, by stratagem, try to take the offensive.

2. In attack, they endeavour to encircle or break through. However, as they are cautious when carrying out an encirclement, we should strive to utilize our manoeuvrability, further encircle the enemy's encircling force, and fight a decisive action at a point where the enemy does not expect it.

Do not use a passive defence if you can help it, as it has the disadvantage of making it easy for the British to build up their strong firepower. On the defensive, choose a position where the front line will not be under the enemy's fire.

3. Although they realize the necessity of a charge, particularly in gaining the final decision in a conflict, they do not concern themselves much about its strength, but rather strengthen their firepower and their positions. The Infantry weapons for hand to hand fighting are few and automatic weapons are many. The infantry just follow the curtain of fire and occupy the ground. For this reason, it is necessary to plan to split them by means of artillery and machine gun fire and isolate the infantry. Then by taking advantage of a good opportunity, we can counter-attack. It is necessary to carry the battle out of the area selected by him so as to not come under the concentrated fire of the enemy artillery, to prevent his pouring fire on the charging infantry.

It is specially necessary when our forces are weak, to rely on the bayonet against the enemy troops who penetrate our positions and to be prepared to drive them back by this means in the final melee.

4. They are also over-cautious in selecting the main objective of their attack in a

meeting engagement and ordinarily do so after the battle has begun and they have

detailed reports of the enemy's dispositions and strength. For this reason, it is

essential to bring about, by swift and resolute action, a decisive battle before the

enemy's preparations are completed.

CHAPTER IV.—A.A. DEFENCES

1. General.

1. Almost all the available information on Japanese Anti-aircraft defences has been obtained by photographic reconnaissance, literally from a bird's eye view.

2. It should always be borne in mind that the Japanese are prepared to use their anti-aircraft artillery in any role which it can conveniently fulfil and A.A. guns may be sited to engage ground troops as well as attacking aircraft.

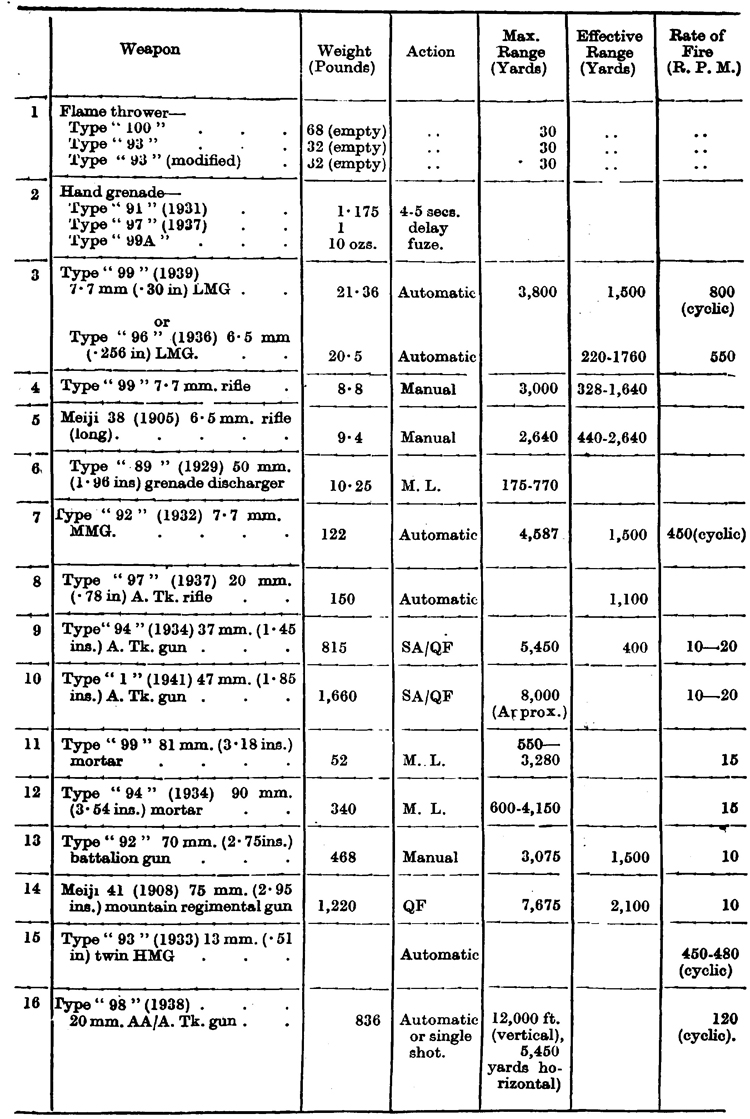

2. Equipment.

3. Generally speaking Japanese A.A. equipment so far identified is about as good as our own was fifteen years ago. A.A. regiments are equipped either with the 105 mm. A.A. gun or else with the 75 mm. A.A. gun. Of the former very few have been identified and little is known of their performance. Several models of the 75 mm. have been produced and both static and mobile versions are employed. The A.A. performance of these guns is not outstanding and it is unlikely that their effect against ground targets will be much better than that of the ordinary 75 mm. or 105 mm. field gun, though an increased range can be expected. Their greater muzzle velocity, however, is likely to make them better anti-tank guns, though because of their size, very vulnerable. Though it is probable, it is not definitely established that they are equipped with A.P. shot as well as H. E.

4. In the light A.A. category, they are believed to have two standard weapons,

the 20 mm. Oerlikon gun and the 0.5 in. heavy machine gun.

The former is an oldish gun, and though reasonably effective, is not likely to compare with modern 20 mm. equipments. A triple barrelled model, which is a logical development of the single barrel gun, has been captured recently.

The latter is possible a ground adaption of the Vickers 0.5 in. aircraft gun. Both these guns fire H. E., Tracer, Incendiary and A.P. ammunition and are likely to be sited so that their versatility can be fully exploited in the defence.

5. To this list must be added captured equipment; its extensive and effective use is only to be expected.

6. Not a great deal is known about their fire control system but the following

types of equipment are probably in use.

Fuze Setter.—Both the 105 mm. and 75 mm. guns are believed to have an automatic fuze setter worked mechanically from the range scale drum.

Height finder.—3 metre base of conventional type.

Sound locators.—Photographs of two types have been seen. One appears to be a small conventional trumpet type, the other a large vane type. No details are known.

Data Computer.—Information received on these instruments distinguishes them from " directors " as made familiar by Vickers and other instruments. It appears the range is announced by the battery commander and the word computer is used to translate the Japanese nomenclature. It would appear that it is used only for elevation and corrections in the azimuth and seems to be a limited application of the idea of mechanical computation and electrical control. Its accuracy is entirely dependent on the accuracy of the. data supplied to it.

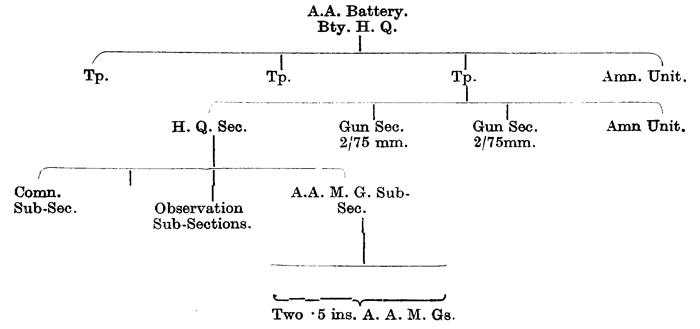

3. Organization.

7. The following organization is compiled from documents captured in the South West Pacific Area :—

4. Tactics and Layouts.

8. Except in China where they met no air opposition worth speaking of, the Japanese have not fought hi country where it is either profitable or possible to employ mechanised forces. Consequently their employment of A. A. in attack or defence in open warfare is still unknown. Reports indicate that they had their A.A. well forward in the Malayan campaign possibly copying the Germans in the battle of France.

9. On static defence however we have a better knowledge of their tactics.

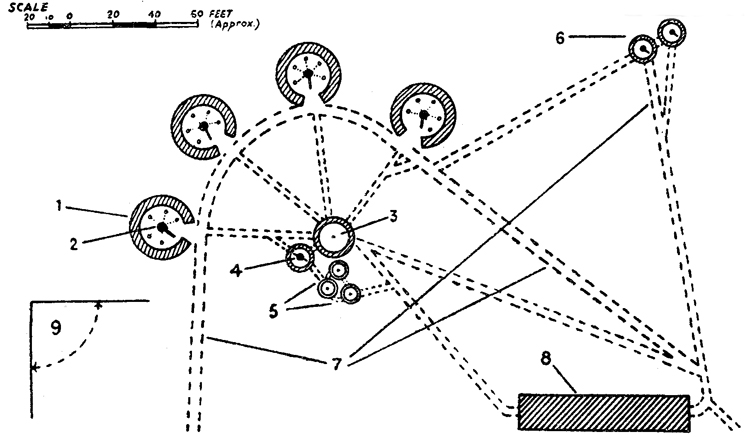

On several airfields in Burma the A.A. guns have been sited with a view to ground defence and in some cases gun positions have been co-ordinated in a trench system. In several cases the guns were raised above ground level presumably to gain a better field of fire. The illustration below shows these tendencies.

In all cases it seems certain that all guns can fire at least down to zero elevation and probably below.

1. Ditch—probably intended as A/Tk. but never completed.

2. Raised emplacements for dual purpose light AA/AT7 guns. (Possibly the 20 mm. Oerlikon)

3. Light A.A. site or L.M.G. emplacements.

4. Small trench systems or weapon pits.

5. Small trench—incomplete.

fl. Site for Heavy A.A. Battery.

7. Shallow Trench.

8. Narrow ditch and earthworks built in conjunction with natural obstacles.

9. L. M. G. positions.

10. Dispersal Bays—These are blast walla for aircraft protection.

Example 2,

11. Originally all guns were sited close to runways and in some oases this practice has been continued. There are two disadvantages to this: firstly when the guns are close to the vital point (V- P.) they engage the enemy aircraft with maximum fire density after it has released its %ombs; secondly the angle at which the aircraft is to the guns approaches 90° as the aircraft gets closer. Recently it has become apparent that the Japanese realize the importance of engaging aircraft early and are siting their guns in suitable positions to do this. They nevertheless appear to attach great importance to the possibility of low-flying and even air-landing attacks on airfields and this might account for their original aim of siting all guns ito cover the runway. The diagram below shows very clearly the outwards movement of defences. All the positions which are now occupied are those on the perimeter while those on islhe airfield itself, the first to be built are now empty.